the theory and practice of translation

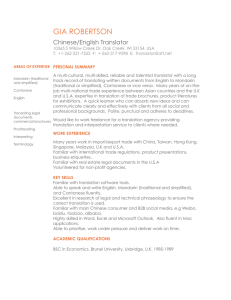

advertisement

UNIVERSITY OF CRAIOVA FACULTY OF LETTERS THE DEPARTMENT OF BRITSH AND AMERICAN STUDIES THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF TRANSLATION Optional Course - COB1 Target population: 3rd year students, Specialization: Romanian (major)-English (minor), Distance Learning Course designer: Senior Lecturer TITELA VÎLCEANU, Ph.D. Course description The course focuses on current approaches and methods in the complex field of translation considered partly science, partly skill, and partly art. Apart from the bulk of theory, students are acquainted with practical aspects of bilingual translation in different fields and registers (literary, business, legal, medical, scientific English) in order to understand that translation is not solely an intuitive work, that there are both universally and cross-culturally ratified problems. Course objectives to make students aware of the status of translation and of translator in the contemporary world and in the universal frame of human communication; to make students understand that translation is an interdisciplinary science; to give students practice in reflective translating; to expose students to a variety of text-types at different levels of difficulty Contents 1. Perspectives on translation and on the translator The status of translation – diachrony and synchrony The status of the translator as communicator. The translator’s competence Monolingual vs. bilingual communication A functional theory of translation Translation vs. translating 2. Language functions and text-types Theories of language The expressive function of language. Expressive texts The informative function of language. Informative texts The vocative function of language. Vocative texts The aesthetic function of language and related texts The phatic function of language. Phaticisms The metalinguistic function 3. Translation methods Formal equivalence vs. dynamic equivalence Translator’s divided loyalties The reader-oriented perspective and text typology The equivalent effect 4. The unit of translation: translation procedures Literal translation: word-for-word translation vs. one-to-one translation Peculiarities of: - transference - naturalisation - cultural equivalent - functional equivalent - descriptive equivalent - bilingual synonymy - through translation - shift - modulation - recognized translation - translation label - compensation - componential analysis - reduction and expansion - paraphrase - equivalence - adaptation Bibliography 1. Bell, R.T. (1991). Translation and Translating. London: Longman 2. Cottom, D. (1998). Text and Culture. The politics of Interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota 3. Freeborn, D. 1996. Style.Text Analysis and Linguistic Criticism, London: Macmillan 4. Hatim, B., Mason, I. (1997). The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge, 5. Jaworski, A., Coupland, N. (1999). The Discourse Reader, London & New York: Routledge 6. Leung, C., 2005, “Convivial Communication : Recontextualizing Communicative Competence” in International Journal of Applied Linguistics, vol. 15, No. 2, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 119 – 144 7. Munday, J., 2001, Introducing Translation Studies. Theories and Applications, London: Routledge 8. Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation. Prentice Hall International (UK) Ltd. 9. Snell-Hornby, M. (1995). Translation Studies. An Integrated Approach, Amsterdam: Benjamins 10. Venuti, L. (1992). Rethinking Translation: Discourse, Subjectivity, Ideology, London: Routledge 11. Vîlceanu, T. (2003). Translation. The Land of the Bilingual, Craiova: Universitaria Evaluation: 70% formal examination, 30% home task assignment Perspectives on translation and on the translator The status of translation – diachrony and synchrony G. Steiner (1975) in his landmark book “After Babel: aspects of language and translation” divides the theory of translation into four main periods: the first period extends from the Roman times up to the publication of Tytler’s “Essay on the Principles of Translation” (1791); the period is characterized by immediate empirical focus; the second period has as a starting point the year 1791 and ends in 1946 with Larbaud’s “Sous l’invocation de St. Jerome”; theory of translation and hermeneutics go hand in hand and at the same time the vocabulary and the terminology of translation as science are developed on a par with the methodology of translation; the third period is much shorter but not downgraded in signification. It extends over three decades (1940s – 1960s) when theory of translation is mostly influenced by machine translation, by the introduction of structural linguistics and of the theory of communication. the last division is from 1960s onwards and it could be seen as a reversion to hermeneutics. Theory of translation is now a hybrid, an interdisciplinary approach in the wide frame of antropology, sociology, rhetoric, poetics, grammar, semantics and pragmatics. The first traces of translation go back around the year 3000 BC in the Egyptian Old Kingdom. The next proof is to be found much later in 300 BC in the Roman translations from the Greek. Cicero and Horace discuss translation in conjunction with the two functions of the poet: the poet fulfilled the universal human duty of acquiring and disseminating wisdom and he was also responsible for the art of making and shaping a poem. Cicero strongly believed that the mind dominates the body in the same way the king rules over his subjects or the father controls his children (what he calls the Law of Reason). Therefore, he favours word for word, sense for sense translation while paying equal attention to the aesthetic criteria of the target language product which should enrich the native language of the readership. Horace takes a stand against overcautious imitation or mimesis. He thinks that the translator should be in the habit of borrowing and coining words, but within limits. Moderation becomes a key word as the translator bears responsibility to the target language readers. During the 14th and 16th centuries, the main preoccupation lies in the translation of the Bible. The translators’ role was to spread the word of God and two criteria were to be met: aesthetic and evangelistic. St. Jerome wrote about stylistic licence and heretical interpretations of the Bible in the attempt to clarify intricate meaning and allegory or parable in the religious text. Between 1380-1384, Wycliffite performs the first translation of the complete Bible in the very spirit of the theory of dominion by grace: man was immediately responsible to God and God’s law. In order that the crucial text may be accessible, the translation is done in the vernacular language. The second Wycliffite Bible is produced between 1395-1396. Chapter 15 contains an elaboration of the stages of the translation process: translation presupposes a collaborative effort of collecting old Bibles and glosses; a comparison of these is necessary; translation cannot be done without counselling with “old grammarians and old divines”; the translation should focus on sentence meaning. Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament in 1525 is intended as a clear version for the layman. Hence, we can state that the aims of the 16th century Bible translators were to spot errors (in some other translations of the sacred text), to produce an accessible and aesthetic vernacular style and to clarify points of dogma. In the medieval education system, translation was a writing exercise and a means of improving oratorical style (in the very tradition established by Quintilian in the 1st century AD): paraphrasing, embellishment, and abridgement to achieve both efficiency and effectiveness. Translation in the Middle Ages can be considered vertical as transposing the text from a source language of prestige (Latin) into the vernacular target language while rendering word for word meaning (interlinear gloss). It can also be seen as horizontal: the source and target languages have similar values (Norman French and English, for instance) and it becomes a matter of imitatio or borrowing. Bacon and Dante are concerned with moral and aesthetic criteria, with loss and coinage in translation. In their opinion, translation resembles stylistics. Dante is further worried by the accessibility of the translated text and by its accuracy. Chaucer is the first to consider translation a skill and to acknowledge that there are different modes of reading and interpreting a source language text. Although decreasing in quantity and importance, the translation of classical authors was not neglected totally. Chapman in his "Epistle to the Reader”, which accompanied his translation of the Iliad, manifests the same range of concerns: avoid word for word renderings; reach the spirit of the original; investigate versions and glosses. The Renaissance is another turning point in the history of the theory of translation. The Elizabethan translators believed in the affirmation of the individual and this is obvious in the replacement of the indirect discourse by the direct one. Wyatt, Surrey translated mostly poems; they saw translation as an adaptation, faithful to the meaning of the poem but also complying with the expectations of the target language readers. The poem was viewed as an artifact of a particular cultural system and the translation should fulfil a similar function in the target language; thus translation was assessed as a primary intellectual activity. The 17th century (Augustan England) is a period of radical changes in the theory of literature and translation. Descartes has already imposed his inductive reasoning and literary critics state rules of aesthetic production (imitation of ancient masters). Sir John Denham speaks of the formal aspect of Art, of the spirit nature of the work and he declares himself against the literal translation of poetry. The translator and author have equal status, but they operate in different social (cultural) and temporal contexts. The translator’s mastery of the two languages is desirable to understand the spirit of the author and to conform to the canons of his age. Pope advises the translator to give a close reading to the original text for considerations of style and manner and to keep alive the ”fire” of the poem. In the 18th century authors are particularly sensitive to the question of overfaithfulness vs. looseness in translation, and of the moral duty to the contemporary reader. The major achievements are the restructurings of Shakespeare’s texts and the reworkings of Racine’s plays. Dr. Johnson discusses the additions that translators can make to texts as every individual has the right to be addressed in his own terms. The metaphor of the translator as painter / imitator is to be decoded as the moral duty the translator has toward the subject and the receiver. The translator will be seen as a painter who is denied the possibility of using the same colours. We have already mentioned that Tytler’s work (1791) is a hallmark in the history of the theory of translation, being considered the first systematic study in English. The principles he announces are best summed up in the following words: complete transcript of the idea of the original work (total surrender of the translator); similar style and manner of the source language and target language text; original composition bearing the stamp of the translator as text creator. The 18th century ‘s ideology is mainly a reaction against rationalism and formal harmony, while allowing the vitalist function of imagination and the freedom of the creative force. Briefly, two tendencies were recorded: translation as a category of thought; translation as the genius work. The problem of meaning is at the core of both trends: if poetry is a separate entity from language, then the translator should be able to read between the lines, to reproduce the text behind the text. Shelley granted translation a lower status: a kind of filling a gap between inspirations, for the sake of the literary graces. The 19th century (The Victorians) is characterized by the need to convey remoteness in time and space and by the concept of untranslatability (which was quite a dogma at the time). Carlyle’s translations from German show an immense respect for the original, based on the writer’s sureness of its worth. We assist at the emergence of an élitist conception of translation, which is addressed to the cultivated reader whilst the average reader is made no concessions as far as his expectations and tastes are concerned. The translation has an archaic flavour, the contemporary life has no room into the space of translation. M. Arnold in his considerations “On Translating Homer” advises the reader to put trust into the scholars and thus translation is devaluated as a mere instrument to bring the target language reader into the source language text. Longfellow went to the extreme and considered the translator a technician and E. Fitzgerald said that “It is better to have a live sparrow than a stuffed eagle”, which is to be understood as version of the source language text into the target language text as a living entity. This patronizing attitude is equivalent to Nida’s “spirit of exclusivism”: the translator is a skilful merchant offering exotic wares to the discerning few. The emergence of the science of the theory of translation is indeed the merit of the 20th century (up to this date, we can speak of commentaries arising from the practice of translating) when advancements and refinements of the theory are the topical issue. The 20th century is marked, in its first half, by literalness, archaizing, the target language second rate merit and by an élite minority addressed by the translator. Translation theory stems from comparative linguistics; it is mainly an aspect of semantics, but it cannot be strictly separated from sociolinguistics and.semiotics. C. S. Peirce laid the foundations of semiotics in 1934 when he stated that no sign has a self- contained meaning, that it is a function of the user / interpretant (the idea echoed in the field of translation, too). Stylistics (Jakobson, 1960, 1966; Spitzer, 1948), in its turn at the crossroads between linguistics and literary criticism, intersects the theory of translation into a joint venture. Ordinary language philosophers (Austin, 1962) take into consideration grammatical and lexical aspects of translation, stating that all sentences depend on a presupposition or truth value to be identified. Austin’s declarative and performative sentences coincide in fact with the distinction between standardized and non-standardized language in translation. Wittgenstein (1958) laid emphasis on the contextual meaning(s) of words while Grice (1975) associated intention to meaning. In its attempt to become a science, theory of translation equips itself with a set of objectives, among which one comes topmost: to determine appropriate methods for the widest possible range of texts or text categories. Translation theory should also provide the framework of principles, rules, hints for translating texts and criticizing translations (a background for problem solving). The practical problems encountered are: the intention of the text; the intention of the translator; the readership and setting of the text; the quality of the writing and the authority of the text. Translation becomes a question of semantic universals or tertium comparationis, a question of splitting words and word series into components to be transferred according to the target language context. The Translator as Communicator In the new millennium, the status of translation is still questioned: art, craft or science? Before making a choice, we must bear in mind that in the closing decade of the 20th century the vast bulk of translations were not literary texts, but economic, technical, medical, legal ones and that the vast majority of translators are professionals engaged in making a living rather than whiling away the time. Translation as a profession has been acknowledged since the foundation of FIT (International Federation of Translators) in 1953, the promulgation of the Translator’s Charter at Dubrovnik in 1963 (which laid down the translator’s code of conduct with regard to confidentiality and open negotiation of fees) and the UNESCO Recommendations of 1976 in Nairobi. Nowadays, staff translators are seen performing various roles: in UNO, UNESCO, NATO and other international organizations translating reports, journals, brochures and facilitating communication (on the basis of common humanity) between representatives of member countries. Their job also includes the translation of classified information, correspondence, publicity, faxes, contracts, training films, etc. As freelancers, they may be translating original papers for academic journals to help researchers with the updating of information, they may be dubbing or sub-titling films or translating all sorts of materials for translation companies. The translator’s task is to continually search and re-search, to deconstruct and reconstruct the text as his/her world is one of dichotomies pertaining to the traditional areas of activity of translators (technical, literary, religious translator, etc), to modes of translating (written, oral) and to the translator’s priorities or focus (literal vs. free, form vs. content, formal vs. dynamic equivalence, semantic vs. communicative translating, translator’s visibility vs. invisibility, domesticating vs. foreignizing translation). In a large sense, the translator is identified with any communicator (whether listeners or readers, monolinguals or bilinguals) as they receive signals containing messages encoded. The translator is a” bilingual mediating agent between monolingual communication participants in two different language communities.”(House, 1977) i.e. the translator decodes messages transmitted in one language and re-encodes them in another. To better understand this principle, it is useful if not necessary to examine the following diagram: Monolingual communication: code sender channel signal (message) channel receiver content The sender selects the message and the code, encodes the message, selects the channel of communication and transmits the signal containing the message. The receiver receives the signal containing the message, recognizes the code, decodes the signal and finally retrieves and comprehends the message. The translator is both a receiver and a producer, a special category of communicator whose behaviour (act of communication) is conditioned by the previous one and whose reception of that previous act is intensive. Unlike other receivers who have a choice whether to pay more or less attention to their listening or reading, the translator interacts closely with the source language text, whether for immediate purpose (simultaneous interpreter) or in a more reflective way (literary translator). In a normative (prescriptive) approach, a good translation is: “that in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work.” (Tytler, 1791). Translation is an abstract concept incorporating both the process/the activity and the product/the translated text. From now on we shall refer to the activity with the term of translating. Of course, any theoretical framework should deal with translation problems and should formulate a set of strategies for approaching this i.e. it should provide a model whose cohesive character is explained by the collection of data. There are no cast-iron rules. Everything is more or less. Newmark (1988) identifies four levels present in various degrees consciously in the mind when translating: 1. the SLT level to which we continually go back to; 2. the referential level – objects, real or imaginary, which we visualize progressively in the comprehension and reproduction process; 3. the cohesive level which is more general, concerned with grammar and presuppositions of the SLT; 4. the level of naturalness, of common language appropriate to the writer/speaker under the circumstances. The fourth level binds translation theory to translating theory and translating theory to practice. The translation practice brings about specifications of the translator competence i.e. knowledge and skills. “The professional (technical) translator has access to five distinct kinds of knowledge: TL knowledge, text-type knowledge, SL knowledge, subject area (real world) knowledge and contrastive knowledge.” (Johnson and Whitelock: 1987, p.137) There is overlap between these five kinds which will be discussed later on. What proves to be more important is adequacy in translation in terms of the specifications of the task and the users’ needs. Bearing in mind Chomsky’s “ideal speaker – hearer” we can postulate the existence of the ideal bilingual reader – writer whose communicative competence consists in a perfect knowledge of both languages. At the same time, this ideal bilingual reader – writer is unaffected by theoretically irrelevant conditions such as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention or interest, errors – random or characteristic, in applying his knowledge in actual performance. The translator’s communicative competence is a multi-component. Grammar competence can be identified with the knowledge and skills to understand and express the literal meaning of utterances. Sociolinguistic competence should be seen as a knowledge of and ability to produce and understand utterances appropriately in context. Discourse competence is the ability to combine form and meaning to achieve unified spoken or written text in different genres. Special attention will be paid to the sociolinguistics variables of power and distance which transcend particular fields and modes of translating. Strategic competence is the same as the mastery of communications strategies which may be used to improve communications or to compensate for breakdowns. Cumulatively, the translator should possess sensitivity to language, linguistic competence in both languages and communicative competence in both cultures in order to create (write neatly, plainly and nicely in a variety of registers), comprehend and use contextfree texts as the means of participation in context – sensitive discourse (he should possess “the ability to research often temporarily the topic of the texts being translated, and to master one specialism” – Newmark: 1991, p.49) Language Functions and the Text Continuum The two functional theories of language to be discussed are Bühler’s (1934) and Jakobson’s (1960), the latter’s being the most frequently applied to translating. According to Bühler, language manifests three main functions: the expressive (Ausdruck), the informative (he calls it “representation”, Darstellung) and the vocative (Appell) which in fact coincide with the main purposes of using language. Jakobson strongly suggests that a theory of language is based on a theory of translation. He adapts Bühler’s theory and proposes a six function model: code [metalinguistic function] addresser [emotive function] code [phatic function] message [poetic function] addressee [conative function] context [referential function] The emotive (expressive) function draws attention upon the mind of the originator of the utterance who expresses his/her feelings irrespective of any response .The focus is on the sender, the meaning is subjective, personal, connotative. E.g. I am tired. Within this linguistic approach, it must be understood that text typology has no clear-cut demarcation lines. Text- types as all embracing categories are commonly defined as classes of texts with typical patterns of characteristics or classes of texts expected to have certain traits for certain overall rhetorical purposes. The text producer feeds his / her own beliefs or goals into the model of the current communication situation, thus also performing as a mediator. Extensive mediation is manifest into text-types. The identification of a text- type can be done through either inductive reasoning (the text as an entity is compared to text theory specifications) or deductive reasoning (text theory is applied to empirical samples). Any categorization or classification is idealized since all texts are hybrids, multifunctional, recognizing dominance of certain peculiar features, showing some emphasis or thrust. We are dealing with a text continuum rather than with borderline instances. It is all about cognitive thresholds or the extent to which text receivers are prone to recognize objects and believe statements. As readers and translators (a translator is said to be a privileged reader as he / she reads in order to produce, to do something with the text not merely to receive it, in order to make a decision that will affect ordinary readers) we should be able to recognize the dominant contextual focus: “Some traditionally established text-types could be defined along FUNCTIONAL lines, i.e. according to the contributions of texts to human interaction. we would at least be able to identify some DOMINANCES, though without obtaining a strict categorization for every conceivable example…In many texts, we would find a mixture of the descriptive, narrative, and argumentative function.” (Beaugrande and Dressler, 1981: p.184) Basically, text typology includes descriptive, narrative and argumentative texts for whose identification and processing we are biologically endowed (we have internalised patterns of recognition of text-type and text organization). With respect to the degree of mediation present in the text, descriptive and narrative texts, can be said to give a reasonably unmediated account of the situation (we are in fact dealing with situation monitoring) whilst in the last type the situation is guided according to the text producer’s goal (situation management). On the other hand, mediation is minimal within the same culture (Western, for instance) and maximal in the case of remote cultures (Western and Muslim). With this specification in mind, we can proceed now to the following stage of classifying texts on account of language functions and further according to rhetorical purposes. Readability (the extent to which a text is suitable for reception among its receivers) is not to be identified with expenditure of the least effort, but rather with a balancing of the required effort and the resulting insights. Newmark (1980) thinks of the following categories as expressive text-types: 1. Serious imaginative literature further divided into lyrical poetry, short stories, novels, plays. Of course, some assistance is needed in the case of plays as far as cross-cultural communication is concerned because plays are addressed to a large audience (we shall make future reference to the concept of audience design). 2. Authoritative statements derive their authority from the high status or reliability and linguistic competence of their originators. Such texts bear the stamp of their authors, although they are mainly denotative, not connotative. E.g. political speeches, documents, statutes and legal documents, academic works of acknowledged authorities Autobiographies, essays, personal correspondence when personal effusions are more often than not mingled throughout the pages. 3. Undoubtedly, the status of the author is a “sacred” one. It proves essential for the translator to be able to distinguish the personal interferences in the texts: unusual collocations, original metaphors, coined words, displaced syntax, neologisms- all that characterizes the idiolect or personal dialect and that seems as natural as possible in a translation. The informative (referential) function focuses on the external situation, on the reality outside language including reported ideas or theories i.e. the subject matter. It refers to entities, states, events, relations which constitute the real world. Content is now the priority. E.g. Here is the 14a. Typical informative texts are textbooks, technical reports, articles in newspapers or periodicals, scientific papers, minutes, etc. Informative texts represent the vast majority of a professional translator’s work in international organizations, private companies, and translation agencies. Therefore, it is important to highlight the salient features of this kind of texts so often dealt with. Scientific texts “explore, extend, clarify society’s knowledge store of a special domain of facts by presenting and examining evidence drawn from observation and documentation” (Beaugrande and Dressler: 1981, p.186). Their evaluation is based on upgrading in the sense that more specialized knowledge is provided for everyday occurrences. Academic papers are written in a technical style characterised in English by an extensive use of the passive forms, present and perfect tenses, latinised vocabulary, jargon, and absence of metaphors. Other technical textbooks concentrate on the use of the first person plural, present tense, dynamic verbs, active voice,basic conceptual metaphors. Popular science or art books (coffee-table books, pulp fiction) cannot deviate from simple grammatical structures, stock metaphors, simple vocabulary and they are always rich in illustrations to accommodate definitions. The vocative function focuses on the readership/addressee/audience. E.g. Alex! Come here a minute! A synonym for vocative would be “calling upon” i.e. calling upon the addressee to act, think or feel, to respond in the way intended by the text. Its appeal is meant to be very direct- think of the vocative case in some inflected languages. This function is also termed conative (denoting effort) and rhetorically it could be considered a strategy of manipulation, of getting active agreement. Typical vocative texts are instructions, publicity, propaganda, persuasive writing (requests, cases, theses) and possibly popular fiction, whose purpose is to sell the book and to entertain the readers. The first factor in a vocative text is the relationship between the writer and the readership. This relationship-of power or equality, command, request, persuasion- is identified through grammatical realizations: E.g. forms of address-T (you, the corresponding French and Romanian tu), and V (you; in French: vous, in Romanian: dumneavoastră); use of the infinitive, imperative, subjunctive, indicative, impersonal forms, of the passive voice; first and/or family name; titles; hypocoristic names. The second factor is that these texts must be written in an immediately comprehensible language. Thus, the linguistic or the cultural level of the SL text has to be reviewed before it is given a pragmatic impact. The poetic/aesthetic function is designed to please the senses, firstly through its actual or imagined sound, and secondly through its metaphors. The rhythm, balance, and contrasts of sentences, clauses and words play their part. The sound effects consist of onomatopoeia, alliteration, assonance, rhyme, metre, intonation, stress. They are encountered in most types of texts: poetry, nonsense, children’s verse/nursery rhymes, some types of publicity (jingles, TV commercials). In translating, there can be often conflict between the expressive and the aesthetic function i.e. between factual truth and beauty. Compromise or compensation is often needed. The phatic function of language is used for maintaining contact with the addressee rather than for imparting new information, for keeping social relations in good repair. It focuses on the channel, on the fact that participants are in contact. In spoken English, apart from tone of voice, it usually occurs in standard phrases or phaticisms. Eg. How are you? You know. Are you well? See you tomorrow. Lovely to see you. What an awful day! Isn’t it hot today? Some phaticisms are universal, others cultural and they should be rendered by standard equivalents, not literal translations. In written English, phaticisms attempt to win the confidence and the credulity of the reader. E.g. of course, naturally, undoubtedly, it is interesting, it is important to note that They often flatter the reader: E.g. It is well-known that… The problem which arises is whether to delete or overtranslate them (increase detail), or to tone down phaticisms: E.g. Illustrissimo Signore Rossi: Mr. Rossi The metalinguistic / metalingual function of language indicates a language ability to explain, name, and criticise its own features. It focuses on the code, on the language being used to talk about language. Dictionaries, grammar books are typically displaying this function. The translation becomes difficult when the items to be rendered from one language to another are language-specific. E.g. supine, ablative, illative, vocative The options range from detailed explanations, examples to a culturally neutral third term. On the other hand, SL expressions signaling metalingual words E.g. strictly speaking, in the true sense of the word, so called, so to speak, as another generation put it have to be treated cautiously as there may be no equivalence of meaning if translated one-to-one. Translation Methods Translating is not a neutral activity. Phrases such as traduttore-traditore, les belles infidèles abound in literature. Undoubtedly, the central problem of translating can be expressed in a peremptory tone: whether to translate literally or freely. The question of the prototypical essence of translation has no solid foundation. The arguments in favour or against one alternative or the other have been going on since at least the beginning of the first century BC. Up to the beginning of the nineteenth century, many writers favoured free translation: the spirit not the letter, the sense not the words, the message rather than the form, the matter not the manner. Writers wanted the truth to be understood. At the turn of the nineteenth century, anthropology had a great impact on linguistics. Cultural anthropology suggested that linguistic barriers were insuperable and that language was entirely the product of culture. The focus / choice of the translator between the two poles was to be carefully thought according to the translators’ orientation towards the social or the individual. No matter the name it bears, the choice is an ideological one: free or literal (literalists, Valéry, Croce), dynamic equivalence or formal equivalence (Nida,1964), communicative or semantic translation (Newmark, 1981), domesticating or foreignizing translation (Venuti, 1995), minimal mediation vs. maximal mediation (Nabokov, 1964). Venuti’s point of view deserves some further attention as he speaks of the English cultural hegemony. In domesticating texts, the translator adopts a strategy through which the TL, not the SL is culturally dominant. Culture-specific terms are neutralised and re-expressed in terms of what is familiar to the dominant culture. If the translation is done from a culturally dominant SL to a minority-status TL, domestication protects SL values. Communicative translation attempts to convey the most precise contextual meaning of the original. Both content and language are readily acceptable and comprehensible. Of all these methods, only semantic and communicative translations fulfil the two major aims of translation: accuracy and economy. Similarities between the two methods are also to be noticed: both use stock and dead metaphors, normal collocations, technical terms, colloquialisms, slang, phaticisms, ordinary language. The expressive components (unusual collocations and syntax, striking metaphors, neologisms) are rendered very closely even literally in expressive texts while in vocative and informative texts they are normalised or toned down (except for advertisements). Scholars, notably House (1977), speak of these two possibilities of choice while attaching them different labels: - semantic translation: art, cognitive translation, overt (culture-linked) translation, overtranslation; - communicative translation: craft, functional or pragmatic translation, covert (culture-free) translation, undertranslation. A semantic translation is likely to be more economical than a communicative translation. As a rule, a semantic translation is written at the author’s linguistic level, a communicative translation at the readership’s. It is also worth mentioning that a semantic translation is most suitable for expressive texts (more specifically for descriptive texts, definitions, explanations), a communicative translation for informative and vocative texts (standardized or formulaic language deserving special attention). Cultural components are transferred intact in expressive translation, transferred and explained with culturally neutral terms in informative translation, replaced by cultural equivalents in vocative translation. A semantic translation remains within the boundaries of the source language culture, assisting the reader only with connotations. A communicative translation displays a generous transfer of foreign elements with an emphasis on force (intended meaning) rather than on message. The conclusion to be drawn from here is that semantic translation is personal, individual, searching for nuances of meaning; it tends to over-translate, yet it aims at concision. On the other hand, communicative translation is social, it concentrates on the message (the referential basis or the truth of information is secured), it tends to under-translate, to be simple and clear, yet it sounds always natural and resourceful (semantic translation may sound awkward and quite unnatural to the target language reader as the language used is often figurative). A semantic translation has to interpret, therefore it does not equal the original. The problem of loss of meaning frequently arises in this case. A communicative translation has to explain, it is more idiomatic and it is often said to be better than the original. A semantic translation recognizes the SLT author’s defined authority, preserving local flavour intact. The tuning with the SL author in semantic translation is marvelously rendered in the following words: “The translator invades, extracts and brings home.” (g. Steiner, 1975: p. 298) Chomsky denied that language is primarily communicative and believed only in the strict linguistic meaning without resorting to cultural adaptations. A communicative translation is a recast in modern culture, shedding new light on universal themes. Nida (1978), doing some pioneering work, clearly states that translating is communicating. Nevertheless, the translator’s freedom seems to be limited in both, as there is constant conflict of interests or loyalties. Although our discussion constantly focuses on the translator and not on the interpreter, it is worth remembering that the interpreter’s loyalties are divided in diplomacy and there is a role conflict for the court interpreter (seating nearer the defence or nearer the prosecution can affect the trust in his impartiality). Translation studies recommend that the overriding purpose of any translation should be the equivalent effect, i.e. to produce the same effect (or one as close as possible) on the readership of the translation as on the readership of the original. This principle is also termed equivalent response or in Nida’s words dynamic equivalence. Dynamic equivalence can be equated with the reader’s shadowy presence in the mind of the translator, and contrasted to formal equivalence, i.e. equivalence of both form and content between the two texts. Newmark (1981) sees the equivalent effect as the desirable result rather than the aim of the translation. He argues that this result is unlikely in two cases: if the purpose of the SL text is to affect and the purpose of the TL text is to inform; if there is a clear cultural gap between SL text and TL text (in fact, translation merely fills a gap between two cultures if, felicitously, there is no insuperable cultural clash. The cultural gap is bridged more easily in a communicative translation as it conforms with the universalist position advocating common thoughts and feelings. Semantic translation follows the relativist position – thoughts and feelings are predetermined by the languages and cultures in which people are born. Consequently, word or word-group is the minimal unit of translation in the former case, the latter showing preference for the sentence. Dealing with text-types, we may say that in the case of communicative translation of vocative texts, the effect is essential, not only desirable. In informative texts, the effect is desirable only in respect of their insignificant emotional impact. The vocative thread in these texts has nevertheless to be rendered with an equivalent purpose aim. In semantic translation, the first problem arises with serious imaginative literature where individual readers are the ones involved rather than a readership. Not to mention, that the translator is essentially trying to render the impact of the SL text on himself, his empathy with the author of the original. The reaction is individual rather than universal. The more cultural (the more local, the more remote in time and space) a text, the less is the equivalent effect unless the reader is imaginative, sensitive and steeped in the SL culture. Cultural concessions are advised where the items are not important for local colour and where they acquire no symbolic meaning. Communicative translation is more likely to create equivalent effect than semantic translation. A remote text will find an inevitably simplified, a version in translation. Equivalent effect can be considered an intuitive principle, a skill rather than an art. It is applicable to any type of text, only the degree of its importance varies from text to text. Translation Procedures The structural view of language as consisting of elements that could be defined both syntagmatically (showing affinities) and paradigmatically (showing substitutability within the system) has affected agreement on the unit of translation. Admittedly, scholars speak of sentence and sentence lower-level components (phrases, words) as the unit of translation when applying translation procedures and of whole texts pertaining to translation methods. The most influential study seems to be Vinay and Dalbernet (1958) to which several authors make constant reference (Newmark, 1988). For our current purpose, only a checklist of translation procedures is useful: literal translation, further subdivided into word-for-word and one-to-one translation – the primary meaning of the word gains overall importance alongside with the norms of the SL grammar; transference / emprunt / loan word / transcription / adoption / transfer posits the problem of necessary and fancy borrowings from the SL into the TL; naturalisation is concerned with the compliance with the TL phonological, morphological, and stylistic specifications; cultural equivalent – the recognition of similar cultural values within the two cultural frameworks, a kind of universal currency to which different labels are attached; functional equivalent – the focus is finding culture-free items; descriptive equivalent – whenever the concept is so culture-bound that it allows only a description or a paraphrase ( an explanatory dictionary or encyclopaedia may provide such information); bilingual / lexical synonymy – intended to capture specialization of meaning; through translation / calque / loan word – mostly concerned with the translation of the names of international organizations; shift / transposition – this procedure comes into play at the syntactic level; modulation – implying a change of perspective (the two languages seem to partition reality from a different point of view); recognized translation – institutional terms have been translated in order to make better acquaintance with such cultural facts; translation label – submitted to refinements in the long run; compensation – omission of some irrelevant or inappropriate information at the moment of decision may be supplied later in the translation and vice versa; componential analysis (CA) – the search for semantic primes or primitives (semes) in the attempt to find the proper equivalent; reduction and expansion – the former if the information seems redundant or recurrent, the latter if there is further need for clarification; paraphrase – the practice is encouraged only if the translator finds it impossible to cater a single equivalent word / phrase; equivalence – the term is restricted to the idiomatic use of language; adaptation – presumably, the most difficult problem for the translator to solve as there is no correspondence of situation in the two languages (the referential base is not secured). Bibliography 12. Bell, R.T. (1991). Translation and Translating. London: Longman 13. Cottom, D. (1998). Text and Culture. The politics of Interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota 14. Freeborn, D. 1996. Style.Text Analysis and Linguistic Criticism, London: Macmillan 15. Hatim, B., Mason, I. (1997). The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge, 16. Jaworski, A., Coupland, N. (1999). The Discourse Reader, London & New York: Routledge 17. Leung, C., 2005, “Convivial Communication : Recontextualizing Communicative Competence” in International Journal of Applied Linguistics, vol. 15, No. 2, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 119 – 144 18. Munday, J., 2001, Introducing Translation Studies. Theories and Applications, London: Routledge 19. Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation. Prentice Hall International (UK) Ltd. 20. Snell-Hornby, M. (1995). Translation Studies. An Integrated Approach, Amsterdam: Benjamins 21. Venuti, L. (1992). Rethinking Translation: Discourse, Subjectivity, Ideology, London: Routledge 22. Vîlceanu, T. (2003). Translation. The Land of the Bilingual, Craiova: Universitaria