Using the Portfolio Interest Exemption

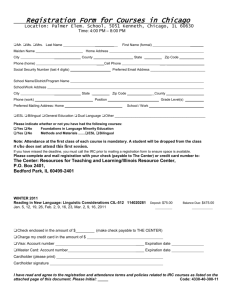

advertisement