Learning Regions as Development Coalitions

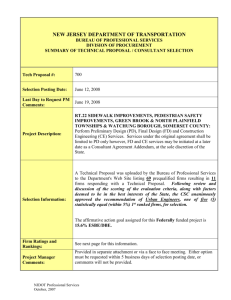

advertisement

Learning Regions as Development Coalitions: Partnership as Governance in European Workfare States?1 By Professor Bjørn T. Asheim, Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture/ Department of Sociology and Human Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1108 Blindern, N-0317 Oslo, Norway; and The STEP Group (Studies in technology, innovation and economic policy), Storgaten 1, N-0155 Oslo, Norway. Published in Concepts and Transformation. International Journal of Action Research and Organizational Renewal, 6, 73-101, 2001. 1 Earlier versions of the paper has been presented at the Regional Studies Association Conference on "Regional Frontiers", European Universität Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder), Germany, 20-23 September 1997, at the IGU Commission on Geography and Public Administration Cambridge Conference, Cambridge, UK, 2-4 July 1998, and at the Second European Urban and Regional Studies Conference on “Culture, place and space in contemporary Europe”, University of Durham, UK, 17-20 September 1998. Learning regions as development coalitions: Partnership as governance in European workfare states? Introduction The understanding of post-Fordist societies as learning economies, in which learning organisations such as learning firms and learning regions play a strategic role, has lately been exposed to criticism. The critique has partly pointed at the structural limits to learning in a capitalist global economy, and partly argued that firms in capitalist societies have always been learning, referring especially to the role of innovation in inter-firm competition (Hudson 1999). Lundvall argues that the concept of a learning economy can be used in two interconnected ways; partly as a theoretical perspective on the economy, and partly as a reference to a specific historical period in which knowledge and learning has attained an increasing importance in the economy, and, thus, is requiring a new theoretical framework for it to be analysed (Lundvall 1996). In this article it will be argued that the concept of a learning economy describes a qualitative change in the development of capitalist economies. This change is represented by the transition from Fordism to Post-Fordism. Thus, the crux of the question of the degree of reality in the rethoric of learning economies and learning regions, lies very much in the view of whether such a transition has really taken place or not. If one argues along with Lundvall (1996), Jessop (1994), Piore and Sabel (1984) and many others, it seems obvious that important structural changes are taking place, and the only theme for discussion is the size and consequences of the changes, and the way these changes in the economy effect the political and institutional set up. This point is taken further by Jessop who links the developments in the global economy from Fordism to Post-Fordism to a parallell restructuring of the state from “the Keynesian welfare state appropriate to the Fordist mode of growth to a Schumpetarian workfare state more suited in form and function to an emerging post-Fordism” (Jessop 1994, 251), and a subsequently “hollowing out” of the nation state, which is a combined effect of a globalising and de-regulated world economy, dominated by TNCs, and the reduced power of nation states due to a transfer of authority to supranational organisations. These changes have led to a shift in the regime of international trade relations from comparative advantage on the basis of relative best access to endowments supplying cheap production factors (e.g. low input costs of raw material and labour) to socially created competitive advantage, resting on ”making more productive use of inputs, which requires continual innovation” (Porter 1998, 78)2. This has on the sub-national, regional level resulted in a growing attention being paid to perspectives and strategies that can secure the innovative capacity of regions in order to foster a regional future of endogenous economic growth. The increased focus on learning regions in the contemporary global economy as a strategy for regional development must, thus, be understood in this double context of changes in the economy as well as of the state. Contrary to the critics, it will be argued that the learning region has a large potential to offer both as a theoretical and normative concept and as a practical metaphor for formulating regional policy. 2 According to Porter “in the new economics of competition, what matters most is not inputs and scale, but productivity – and that is true in all industries” (Porter 1998, 85). 2 What is a “learning region”? In his article presenting the “sympathetic” critique of the idea of a learning region, Hudson (1999) does not explicitly define the concept. However, others have made such attempts. Florida, in an article arguing for a central role of regions in “the new age of global, knowledge-intensive capitalism” (Florida 1995, 527), defines learning regions as “collectors and repositories of knowledge and ideas, ....(which).... provide an underlying environment or infrastructure which facilities the flow of knowledge, ideas and learning” (Florida 1995, 528). Hassink (1998) summerises several definitions of learning regions as “regional development concepts in which the main actors are strongly, but flexibly connected with each other and in which both interregional and intraregional learning is emphasised” (Hassink 1998, 6). The Swedish National Institute for Working Life in a project together with The Swedish EU Programme Office on “Stronger Partnership for Learning Regions” consider the perspective of learning regions as a means to “initiate and provide the basis for co-operation between enterprises in regions, local public bodies, organisations and other interest groups” (The National Institute for Working Life 1997, 1). All these definitions and elaborations of the concept of a learning region emphasise the role played by regional based learning organisations. This underlines the important role of innovation, understood as contextualised social processes of interactive learning, in a postFordist learning economy, which highlights the significance of building social capital in order to foster co-operation as well as promoting the principle of broad participation in intra- and inter-firm networks. The concept of a learning region could, then, precisely be used to describe a region with an economy embedded in "institutional thickness", and characterised by innovative activity based on localised, interactive learning, and co-operation promoted by organisational innovations in order to exploit "the benefits of learning based competitiveness" (Amin and Thrift 1995a, 11). This points at a broad understanding of a learning region as representing the territorial and institutional embeddednesss of learning organisations and interactive learning, which, however, could not be said to be similar to a regional innovation system, and, consequently, be used synonymously (Hassink 1998), even if innovation systems, especially in its broad definition (Lundvall 1992), must constitute a core element of learning regions (Asheim and Pedersen 1999). Learning regions should be looked upon as a policy framework or model for formulations of long term partnership-based development strategies initiating learning-based processes of innovation, change and improvement. In the promotion of such innovation supportive regions the inter-linking of co-operative partnerships ranging from work organisations inside firms via inter-firm networks to different actors of the community, understood as “regional development coalitions”, will be of strategic importance. By the concept “development coalition” is meant a bottom-up, horizontally based co-operation between different actors in a local or regional setting, based on a socially broad mobilisation and participation of human agency. (Ennals and Gustavsen 1999a). The attractiveness of the concept of learning regions to planners and politicians is to be found in the fact that it at one and the same time promises both economic growth and job generation as well as social cohesion. As such, learning regions must be analysed as an answer and challenge to contemporary changes in the global economy and the subsequently strategic policy reorientations of the nation state. 3 The building blocks of the concept of learning regions The concept of “learning regions” has been used in at least three different contexts. The concept was first introduced by economic geographers in 1995 (Florida 1995), when they used it to emphasise the role played by co-operation and collective learning in regional clusters and networks in order to promote the innovativeness and competitiveness of firms and regions in the globalising learning economy (Asheim 1997). This approach was clearly inspired by the rapid economic development in the “Third Italy”, which drew the attention towards the importance of co-operation between SMEs in industrial districts and between firms and local authorities at the regional level in achieving international competitiveness (Asheim 1996). The second approach expressing (more indirectly) the idea of learning regions originates from the writings of new evolutionary and institutional economics on the knowledge and learning based economy, arguing that "regional production systems, industrial districts and technological districts are becoming increasingly important" (Lundvall 1992, 3), and from Porter, who emphasises that "the process of clustering, and the interchange among industries in the cluster, also works best when the industries involved are geographically concentrated" (Porter 1990, 157). These ideas are more or less the same as the ones Perroux, another Schumpetarian inspired regional economist, presented in the early 1950s. According to Perroux, the growth potential and competitiveness of growth poles can be intensified through territorial agglomeration by exploiting localisation (external) economies (Haraldsen 1994, Perroux 1970). The third approach, which conceptualises learning regions as regionally based development coalitions, has lately been applied by representatives of the socio-technical school of organisational theory taking their knowledge of how to form intra- and inter-firm learning organisations based on broad participation out of the firm context and using it to establish learning organisations at the regional level (i.e. learning regions) (Ennals and Gustavsen 1999a). This organised form of bringing the society inside the firm through learning organisations based on broad participation, and supported by labour market legislation as well as a strong tradition of co-operation between the labour market organisations, is in many aspects the opposite way of achieving a fusion of the economy with the rest of society (Piore and Sabel 1984) than the industrial district model, in which the firm is contextualised through its embeddedness in spatial structures of social relations. These contrasting models of contextualising the firm also reflect the alternative interpretations of social capital, i.e. as rooted in the “civicness” of communities (industrial district) or as formal organisations on the system level of societies (development coalition). However, while the economic geograhic and the evolutionary economics approaches are strong on the innovation dimension, the action research approach of the socio-technical school has mainly focused on the organisational principle of broad participation. Thus, it is an important task to merge these approaches in order to obtain a coherent model or policy framework for formulations of partnership-based development strategies in order to achieve economic growth, employment generation as well as social cohesion. 4 a) Economic geographical studies of industrial districts in the Third Italy The rapid economic development in the "Third Italy", based on territorial agglomerated SME's in industrial districts (ID), has drawn an increased attention towards the importance of co-operation between firms and between firms and local authorities in achieving international competitiveness (Brusco 1990). Pyke (1994) underlines the close inter-firm co-operation and networks as well as the existence of a supporting institutional infrastructure at the regional level (e.g. centres of real services) as the main factors explaining the success of EmiliaRomagna in the "Third Italy". According to Dei Ottati, "this willingness to cooperate is indispensable to the realization of innovation in the ID which, due to the division of labour among firms, takes on the characteristics of a collective process. Thus, for the economic dynamism of the district and for the competitiveness of its firms, they must be innovative but, at the same time, these firms cannot be innovative in any other way than by cooperating among themselves" (Dei Ottati 1994, 474). The European experience of industrial districts has become a major point of reference in the recent international debate on industrial policy promoting regional endogenous development. Of significant importance is the understanding of industrial districts as a "social and economic whole", where the success of the districts is as dependent on broader social and institutional aspects as on economic factors in a narrow sense (Pyke and Sengenberger 1990). Bellandi emphasises that the economies of the districts originate from the thick local texture of interdependencies between the small firms and the local community (Bellandi 1989), and Becattini maintains that "the firms become rooted in the territory, and this result cannot be conceptualised independently of its historical development" (Becattini 1990, 40). Thus, the major differentiating factors in play in the Third Italy are not the techno-economic structures as such, but rather the importance of non-economic factors for the economic performance of the regions. Brusco et al. (1996) maintain that the “experience in EmiliaRomagna has demonstrated that competitiveness on global markets is not a contradiction to high labour cost, high incomes and a fair distribution of income; on the contrary, we would claim that a fair income distribution is a necessary condition (although not sufficient) for consensus, and consensus and participation are an indispensable prerequisite for economic success” (Brusco et al. 1996, 35). Furthermore, the economic and social development of the region has not simply been “the result of a “spontaneous” development but, rather, it has been assisted by a process of institutional building aimed at the creation of an intermediate governance structure capable of establishing a positive enabling environment for firm development” (Bianchi 1996, 204). b) Evolutionary economical theories of post-Fordist societies as ”learning economies” Lundvall and Johnson use the concept of «learning economy» when referring to the contemporary post-Fordist economy dominated by the ICT-related (information, computer and telecommunication) techno-economic paradigm in combination with flexible production methods and reflexive work organisations (i.e. learning organisations and functional flexible workers) (Lundvall and Johnson 1994). In addition the learning economy is firmly based on 5 «innovation as a crucial means of competition» (Lundvall and Johnson 1994, 26). These perspectives of the "learning economy" are based on the view that knowledge is the most fundamental resource in a modern capitalist economy, and learning the most important process (Lundvall 1992), thus making the learning capacity of an economy of strategic importance to its innovativeness and competitiveness. When reference is made to innovation as a crucial means of competition in the learning economy it is not the previous hegemonic linear model of innovation of the Fordist era of industrial organisation and production3, which is being thought of, but a new theoretical understanding of innovation as basically a socially and territorially embedded, interactive learning process, which, thus, cannot be understood independent of its institutional and cultural contexts (Lundvall 1992). This more sociological view on innovation implies a criticism of the traditional dominating linear model of innovation, as the main strategy for national R&D policies, of being too "research-based, sequential and technocratic" (Smith 1994, 2). The criticism implies another and broader view of innovation as a social as well as a technical process, as a non-linear process, and as a process of interactive learning between firms and their environment (Lundvall 1992, Smith 1994). This alternative model could be referred to as a bottom-up interactive innovation model (Asheim and Isaksen 1997). The interactive innovation model puts emphasis on “the plurality of types of production systems and of innovation (science and engineering is only relevant to some sectors), “small” processes of economic co-ordination, informal practices as well as formal institutions, and incremental as well as large-scale innovation and adjustment” (Storper and Scott 1995, 519). Porter emphasises that the reproduction and development of competitive advantage requires continual innovation, which in a learning economy is conceptualised as a localised interactive learning process, promoted by clustering, networking and inter-firm co-operation. This new and alternative conceptualisation of innovation as an interactive learning process means an extension of the range of branches, firm-sizes and regions that can be viewed as innovative, also to include traditional, non R&D-intensive brances, often constituted by SMEs and located in peripheral regions. The basic critique of the linear model is precisely the equation of innovative activities with R&D-intensity. The majority of SMEs are in branches which are not R&D-intensive, but which could still be considered to be innovative (e.g. the importance of design in making furniture manufactures competitive and moving them up the value-added chain). One further, important implication of this view on innovation is that it makes the distinction between high-tech and low-tech branches and sectors, which is a product of the linear model, irrelevant, as it maintains that all branches and sectors can be innovative in this broader sense. According to Porter, “the term high-tech, normally used to refer to fields such as information technology and biotechnology, has distorted thinking about competition, creating the misconception that only a handful of businesses compete in sophisticated ways. In fact, there is no such thing as a low-tech industry. There are only low-tech companies – that is, companies that fail to use world-class technology and practices to enhance productivity and innovation” (Porter 1998, 85-86). Following Porter, this implies that it is 3 Fordism is here defined as "an allegedly hegemonic form of industrial organization" (Sayer 1992, 194), and not simply as an assembly line-based organisational model. 6 possible in all branches and sectors to find productive and innovative firms enjoying competitive advantages on the global markets. Thus, this theoretical perspective also broaden the scope for a policy of strong competition for post-Fordist learning economies (Storper and Walker 1989), i.e. competition building on innovation and differentiation strategies, in contrast to weak competition based on price competition. c) Organisational theoretical action research on learning organisations as ”development coalitions” Hudson in his criticism of the concept of learning regions questions the impact of the growth of “new and enriching and empowering forms of work” as a result of the increased importance of knowledge and learning (Hudson 1999, 60). Referring to what he sees as “necessary and possible” in a capitalist economy he will not in general accept the tendency towards a reduction in the relative significance of “the alienated and deskilled mass worker” (Hudson 1999, 60). However, changes in work organisation away from such working conditions have been underway since the 1940s and 50s starting with the studies by the sociotechnical school of organisational theory, which also is a forerunner for today’s research on development coalitions. There has been a transformation of the organisation of the labour process from a work organisation on the basis of Fordist and Taylorist principles of a strict division between intellectual and manual work, building on the ideas of “scientific management”, to a reflexive based work organisation in which central, skilled, functional flexible workers are more important than un- or semiskilled, numerical flexible, peripheral workers. In such a reflexive work organisation of functional flexible core workers it is easy to understand the potential importance of intra- and inter-firm learning organisations based on broad participation, in which interactive learning plays a strategic role. In their work, Lundvall and Johnson argue that "the firm's capability to learn reflects the way it is organised. The movement away from tall hierarchies with vertical flows of information towards more flat organisations with horizontal flows of information is one aspect of the learning economy" (Lundvall and Johnson 1994, 39). This is in line with Scandinavian experiences,4 which have shown that flat and egalitarian organisations have the best prerequisites of being flexible and learning organisations, and that industrial relations characterised by strong involvement of functional flexible, central workers is important in order to have a working "learning organisation". Such organisations will also result in well functioning industrial relations, where all the employees (i.e. the (skilled) workers as well as the managers) will have a certain degree of loyalty towards the firm.5 All experience shows that "the process of continous improvement through interactive learning and problem-solving, a process that was pioneered by Japanese firms, presupposes a workforce that feels actively committed to the firm" (Morgan 1997, 494). Brusco - with special 4 Referred to as, for example, "Kalmarism" in contrast to "Fordism", "Neo-Taylorism" and "Toyotism" in the international academic literature (Leborgne and Lipietz 1992). 5 Leborgne and Lipietz (1992) disagrees in the possibilities of combining involvement and flexibility. They argue that “collective involvement and flexibility are incompatible”, because “external rigidity of the labor market (is) associated with negotiated involvement of the workers” (Leborgne and Lipietz 1992, 339). However, partly the authors reduce flexibility to only be a question of numerical flexibility, and neglect the possibility of functional flexibility, and partly, given the presence of functional flexible, central workers in the organisation, there exists a potential trade-off between influence and loyalty. 7 referance to the industrial districts of Emilia-Romagna - points to the dominating model of production in the districts "that was able to be efficient and thus competitive on world markets, in which efficiency and the ability to innovate were achieved through high levels of worker participation and were accompanied by working conditions that were acceptable" (Brusco 1996, 149). In general, Porter points out that ”labor-management relationships are particularly significant in many industries because they are so central to the ability of firms to improve and innovate” (Porter 1990, 109). Such co-operative tradition is embedded in specific cultural, social and political-institutional factors. In Norway, egalitarian social structures are still a prominent part of the society compared to most other (non-Nordic) developed nations. Thus, the contemporary Norwegian society is characterised by a low level of conflict both in the society as such and in the worklife, the educational level is high, the culture is rather homogenous, and equality represents an ideal as well as a reality in most cases. The trade unions are representative and very co-operative oriented, and the political situation is characterised by a high degree of stability (Nylehn 1995). Thus, it could be argued that the Norwegian society is characterised by a culture in which cooperation is both recognised and attributed value to, and that this can have positive consequences for firms with respect to loyalty, flexibility and general positive attitudes towards work at the micro level as well as to the social regulation of the labour market at the macro level. However, it is important that co-operation is based on broad participation in order to have a significant and lasting effect on innovativeness and competitiveness, i.e. all workers in a firm have to be involved in the continuous improvement work within a learning organisation aiming at increased productivity and quality specifically and contributing to enterprise development in general (Nylehn 1995). The presence of social capital in the form of a strong tradition of co-operation adds to the high level of human capital of the work force in a synergetic way, and represents an international competitive advantage, not the least beacuse it implies a next to immediate implementation of decisions, since they have been taken in consensus oriented learning organisations based on broad participation. A strong and broad involvement within an organisation will make it easier to use and diffuse informal or "tacit", non-R&D based, knowledge, which in a "learning economy" has a more central role to play in securing continuous innovation. Transactions with "tacit" knowledge within and between networking organisations require trust, which is easier to establish and reproduce in flat organisations than in hierarchical ones. In a study of successful intra-firm reorganisation of SMEs in Baden-Württemberg Herrigel reports that one company "set out to constitute "trusting" relations among all actors within the firm, regardless of role or position in the organization, which were informed by mutual respect. It discouraged thinking in terms of hierarchy and status and made all information about the company available to everyone within it" (Herrigel 1996, 46). In organisations characterised by an authoritarian management style the attitude of the employees will often be to keep "the relevant information to themselves" (You and Wilkinson 1994, 270). 8 Agglomeration and localised learning The perspective of "learning economies" and modern innovation theory emphasises that learning is a localised, and not a placeless process (Lundvall and Johnson 1994, Storper 1995a). This view is supported by Porter, who argues that "competitive advantage is created and sustained through a highly localised process. Differences in national economic structures, values, cultures, institutions, and histories contribute profoundly to competitive success" (Porter 1990, 19). Accordingly, Porter argues that "the building of a "home base" within a nation, or within a region of a nation, represents the organizational foundation for global competitive advantage" (Lazonick 1993, 2). In contrast to this, Reich in his book "The Work of Nations" (1991) argues that "the globalization of industrial competition has led to a global fragmentation of industry, thus making national industries and the national enterprises within them less and less important entities in attaining and sustaining global competitive advantage" (Lazonick 1993, 2). According to Reich, "the work of nations" is the result of activities that take place in the national territory, and not of nationally-based companies (Reich 1991, Storper 1995b). However, Reich's analysis misses the historical and contemporary insights of the importance of territory (i.e. location and agglomeration) specifically and non-economic factors (i.e. institutions, social structures, traditions etc.) in general, or in Piore and Sabel's words, the "fusion" of the economy with society (Piore and Sabel 1984), for the performance of an economy. The major impact of Porter's book "The Competitive Advantage of Nations" (1990) is represented by a change in the understanding of the strategic factors which promote innovation and economic growth. Porter's main argument is that these factors are a product of localised learning processes, and that the importance of clusters is that they represent the material basis for an innovation based economy, which represents "the key to the future prosperity of a nation" (Lazonick 1993, 2). Porter's cluster is basically an economic concept indicating that "a nation's successful industries are usually linked through vertical (buyer/supplier) or horizontal (common customers, technology etc.) relationships" (Porter 1990, 149). However, in an article from 1998, Porter restricts his definition of cluster to only denote ”geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field” (Porter 1998, 78).6 A dynamic, processual understanding of competitiveness clearly indicates that enterprises in order to keep their position in the global market, must focus on developing their own core competencies through transforming themselves into learning organisations. But internal restructuring alone cannot sustain the competitiveness of firms in the long run. As firms are embedded in regional economies they are very much depended on a favourable economic environment.The main argument for territorial agglomeration of economic activity in a contemporary capitalist economy is that it provides the best context for an innovation based 6 In my view there is a need to operate with clusters in both conceptualisations, as it is a quite normal situation to find (geographical) clusters of specialised branches being part of a national (economic) cluster of the same branches. 9 learning economy.7 In a learning economy the competitive advantage of firms and regions is based on innovations, and innovation processes are seen as social and territorial embedded, interactive learning processes. According to Amin and Thrift, this forces a re-evaluation of "the significance of territoriality in economic globalisation" (Amin and Thrift 1995a, 8). Thus, a strong case is made today that regional agglomerations are growing in importance as a mode of economic coordination in post-Fordist learning economies (Asheim and Isaksen 1997, Cooke 1994). In general, “geographical distance, accessibility, agglomeration and the presence of externalities provide a powerful influence on knowledge flows, learning and innovation and this interaction is often played out within a regional arena” (Howells 1996, 18). Close co-operation with suppliers, subcontractors, customers and support institutions in the region will enhance the process of interactive learning and create an innovative milieu favourable to innovation and constant improvement. The spatial proximity of interacting firms is an important enabling factor in stimulating inter-firm "learning networks" involving long-term commitment. Håkonsson claims that "the importance of proximity is particularly noticeable in horizontal relationships, but it is not altogether absent in the case of vertical relations" (Håkonsson 1992, 125). Thus, such co-operation can result in a largely improved innovative capacity of firms within regional agglomerations. This influences the performance of the firms and strengthens the competitive advantage of regions. Generally, the innovative capacity at the regional level can be promoted through identifying “the economic logic by which milieu fosters innovation” (Storper 1995a, 203). Specifically, it is important to underline the need for “enterprise support systems, such as technology centres or service centres, which can help keep networks of firms innovative” (Amin and Thrift 1995a, 12). Localised learning is not only based on tacit knowledge, as we shall argue that contextual knowledge also is constituted by ”sticky”, codified knowledge. This refers to disembodied knowledge and know-how which are not embodied in machinery, but are the result of positive externalities of the innovation process, "which can occur independently of changes in physical capital stock" (de Castro and Jensen-Butler 1993, 1) .... and to "untraded interdependencies", i.e. "a structured set of technological externalities which can be a collective asset of groups of firms/industries within countries/regions" (Dosi 1988, 226).8 Disembodied knowledge can be both tacit and codified. However, such knowledge is, as pointed out by de Castro and Jensen-Butler, generally highly geographical immobile, and is 7 Porter (1998) underlines that “what happens inside companies is important, but clusters reveal that the immediate business environment outside companies plays a vital role as well. This role of locations has been long overlooked, despite striking evidence that innovation and competitive success in so many fields are geographically concentrated” (Porter 1998, 78). 8 According to de Castro and Jensen-Butler "rapid disembodied technical progress requires [...] a high level of individual technical capacity, collective technical culture and a well-developed institutional framework [...] (which) [...] are highly immobile in geographical terms" (de Castro and Jensen-Butler 1993, 8). Dosi argues that "untraded interdependencies" represent "context conditions" which generally are country- or region-specific, and of fundamental importance to the innovative process (Dosi 1988). Storper emphasises the importance of regions in underpinning "untraded interdependencies" between actors, generating region-specific material and nonmaterial assets in production allowing actors to promote technological and organisational change (Storper 1995c). Finally, Amin and Thrift precisely underline "the role of localised "untraded interdependencies" in securing learning and innovation advantage in inter-regional competition" (Amin and Thrift 1995a, 12). 10 often constituted by a combination of place-specific experience based, tacit knowledge and competence, artisan skills and R&D-based knowledge (Asheim 1999). Thus, some codified knowledge can be a product of localised rather than placeless learning. This implies, for example, that the adaptability of this contextual form of codified knowledge is dependent upon, and limited by artisan skills and tacit knowledge (Asheim and Cooke 1998). Lundvall (1996) argues in a similar way when he maintains that “the increasing emergence of knowledge-based networks of firms, research groups and experts may be regarded as an expression of the growing importance of knowledge which is codified in local rather than universal codes. The skills necessary to understand and use these codes will often be developed only by those allowed to join the network and to take part in a process of interactive learning” (Lundvall 1996, 10-11). This points out that "whilst knowledge in the form of embodied technical progress can be exported independently of social institutions, such knowledge in its disembodied form cannot be absorbed independently of such institutions" (de Castro and Jensen-Butler 1993, 3). The rationale behind endogenous development is precisely "to use this social organization to generate innovation and economic development" (Lazonick and O'Sullivan 1995, 4). The formation of learning regions understood as regional development coalitions represents a strategy of promoting such innovation supportive regions through the creation of organisations and institutions as public-private partnerships, for example, in accordance with the network approach to regional innovation systems based on partnerships amongst large, private firms, government, universities, intermediary agencies, research institutes and small firms (Asheim and Cooke 1999). This perspective emphasises the importance of organisational (social) and institutional innovations to promote co-operation, primarily through the formation of dynamic flexible learning organisations. Lundvall and Johnson underline that "the firms of the learning economy are to a large extent "learning organisations" (Lundvall and Johnson 1994, 26). A dynamic flexible "learning organisation" can be defined as one that promotes the learning of all its members and has the capacity of continuously transforming itself by rapidly adapting to changing environments by adopting and developing innovations (Pedler et al. 1991, Weinstein 1992). The hegemonic techno-economic paradigm of the post-Fordist "learning economy" is to a very large extent (and more than previous techno-economic paradimgs) dependent on organisational innovations to have its potential exploited, and the more important organisational innovations are, the more important interactive learning can be considered to be for the promotion of innovations in general as organisational innovations enable the formation of learning organisations in post-Fordist societies. On the other hand it can be argued that the application of the ICT techno-economic paradigm stimulates organisational innovations, as the ICT technologies are very adaptable to all kinds of network organisations, and, thus, supports the rise of the “network society” (Castells 1996). The strategic role played by co-operation in a learning economy is underlined by the understanding of interactive learning as a fundamental aspect of the process of innovation (Asheim 1996). What this broader understanding of innovation as a social, non-linear and interactive learning process means, is a change in the evaluation of the importance and role played by socio-cultural and institutional structures in regional development from being looked upon as mere reminiscences from pre-capitalist civil societies (although still 11 productive), to be viewed as necessary prerequisites for regions in order to be innovative and competitive in a post-Fordist learning economy. Thus, if these observations are correct, this represents new "forces" in the promotion of technological development in capitalist economies, implying a modification of the overall importance of competition between individual capitals. Of course, the fundamental forces in a capitalist mode of production constituting the technological dynamism are still caused by the contradictions of the capitalcapital relationship. However, Lazonick argues, referring to Porter's empirical evidence (Porter 1990), that "domestic cooperation rather than domestic competition is the key determinant of global competitive advantage. For a domestic industry to attain and sustain global competitive advantage requires continuous innovation, which in turn requires domestic cooperation" (Lazonick 1993, 4). Cooke (1994) supports this view, emphasising that "the cooperative approach is not infrequently the only solution to intractable problems posed by globalization, lean production or flexibilisation" (Cooke 1994, 32). Using this perspective on networks, competitive advantage is achieved internally through inter-firm co-operation and exploited externally through competition with firms of the "outside" world. According to Harvard Business Review, "the new competition [...] is among alliances of firms, not individual firms" (Rosenfeld 1996, 247; Gomes-Casseres 1994). Lazonick argues that "to fight foreign rivals requires a suspension of rivalry in order to build value-creating industrial and technological communities. Unless social organizations are put in place that can engage in innovation, heightened domestic rivalry will lead to decline" (Lazonick 1993, 8). Non-economic factors in economic development: Trust and networking as social capital As a consequence of the increased awareness and recognition of intra- and inter-firm cooperation and networking as important factors in promoting international competitiveness, "the issue of (extended) trust has come to the fore" (Humphrey and Schmitz 1996, 23). According to Lipparini and Lorenzoni "a high dose of trust serves as substitute for more formalised control systems" (Lipparini and Lorenzoni 1994, 18). In this context a critical question is how it is possible to develop the necessary extended trust as the basis for interfirm co-operation and networking in order to sustain collective efficience, defined as "the competitive advantage derived from local external economies of joint action" (Humphrey and Schmitz 1996, 28). Through co-operation and networking the ambition is to create "strategic advantages over competitors outside the network" (Lipparini and Lorenzoni 1994, 18). However, to achieve this it is important that the networks are organised in accordance with the principle of the "strength of weak ties" (Granovetter 1973). Grabher argues that "loose coupling within networks affords for favourable conditions for interactive learning and innovation. Networks open access to various sources of information and thus offer a considerably broader learning interface than is the case with hierarchical firms" (Grabher 1993, 10). Leborgne and Lipietz (1992) maintain that the more horizontal the ties between the partners in the network are, the more efficient the network as a whole is. This is also emphasised by Håkansson, who points out that "collaboration with customers leads in the first instance to the step-by-step kind of changes (i.e. incremental innovations), while collaboration with partners 12 in the horizontal dimension is more likely to lead to leap-wise changes (i.e. radical innovations)" (Håkansson 1992, 41). Generally Leborgne and Lipietz argue that "the upgrading of the partner increases the efficiency of the whole network" (Leborgne and Lipietz 1992, 399). This can be illustrated by an example from the "Third Italy", where a firm started to cooperate with its suppliers in developing new products (i.e. product innovations) in order to institutionalise a continual organisational learning process. This co-operation played a central role in shortening the product cycle, improving the product quality and increasing the competitiveness of the firm (Bonaccorsi and Lipparini 1994). The firm redefined the relations to its major suppliers based on the recognition that "a network based on long-term, trustbased alliances could not only provide flexibility, but also a framework for joint learning and technological and managerial innovation. To be an integral partner in the development of the total product, the supplier must operate in a state of constant learning, and this process is greatly accelerated if carried out in an organizational environment that promotes it" (Bonaccorsi and Lipparini 1994, 144). Such enterprise development is based on what Lazonick and O’Sullivan (1996) call the innovative enterprise. An innovative business enterprise does not take an achieved competitive advantage as given, as it can be eliminated through imitation. Thus, it must be continually reproduced through innovation. However, the innovation process has to be based on collective learning inside the business enterprise or network of co-operating firms to give the firm a possibility of developing their specific competitive advantage over competing enterprises. In this way collective learning stands in contrast to individual learning, where the improved skills are sold and purchased on the labour market at a given price (Lazonick and O’Sullivan 1996, Storper 1997). According to Lazonick and O’Sullivan, innovation processes in the advanced knowledge based society are characterized by such collective learning, which depends on business enterprises creating social organisations (e.g. learning organisations and networks) enabling collective learning to take place (Lazonick and O’Sullivan 1996). Generally, Tödtling notes that "subcontracting relationships [...] have changed substantially: they are no longer confined to the goal of cost savings only, but increasingly include aspects of product quality and technology development and improvement. This implies more selective and fewer but stronger relationships between firms since they cover not just production but also quality control, joint research and development as well as information exchange on and coordination of future planning" (Tödtling 1995, 14). Herrigel refers to cases of successful adjustment and restructuring of SMEs in Baden Württemberg, where "relations with suppliers [...] were intensified so that important providers were drawn directly into the development process" (Herrigel 1996, 47). Such a reorganisation of networking between firms can be described as a change from a domination of vertical relations between principal firms and their subcontractors to horizontal relations between principal firms and suppliers. Patchell refers to this as a transformation from production systems to learning systems, which implies a transition from "a conventional understanding of production systems as fixed flows of goods and services to dynamic systems based on learning" (Patchell 1993, 797). 13 When talking about the importance of non-economic factors for the performance of an economy we are, thus, referring to socio-cultural (i.e. institutional) as well as politicalinstitutional (i.e. organisational) factors, which incorporate historical and territorial dimensions. In more recent writings within economic sociology the concept of social capital has come into use. Social capital represents an extension of the “capital” concept from the classical conomists use of physical capital (i.e. assets that generate income) and the neoclassical economics introduction of human capital, focusing on the importance of education and training of the labour force, to capture the role social and cultural aspects in a broad sense are playing in influencing economic performance by “encompassing the norms and networks facilitating collective action for mutual benefit” (Woolcock 1998, 155). Social capital can depend on the level of “civicness” in the civil society as well as on the degree of formal organisation in the public sphere. According to Putnam, social capital means “features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust, that facilitate action and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Putnam 1993, 35-36). As such, social capital can be viewed as a structural property of larger groups (Woolcock 1998), as it is a common value to several people, and also represents a set of expectations, obligations, and social norms which govern the behaviour of individuals in society (Greve 1999), or what in other contexts is called “institutional thickness” (Amin and Thrift 1995b). However, being aware of the fact that Europe is characterised by cultural diversity, and knowing from empirical research that the existence of entrepreneurial as well as innovative activity is not evenly spread out geographically, this indicates that not all cultural settings represent social capital (i.e. the problems of applying the industrial district model in parts of Southern Italy due to lack of trust and the dominance of strong ties). This points to the importance of looking at social capital not only as something which has more or less organically developed in specific geographical and historical settings, but as something that could be developed through various forms of policy interventions. Examples of such initiatives could be the establishment of centres of real services in the Third Italy, or the network programmes of Denmark and Norway, which all are aimed at promoting and stimulating the collective capacity for co-oparation and networking. Lorenz has, in a study from the Lyon region in France, showed that trust and co-operation among firms can be intentionally created through a "partnership" strategy, which is based on establishing long term relations concerning the amount, price and quality of work between the client firms and their subcontractors (Lorenz 1992). In a study from the US, Sabel also points to the possibilities of creating trust by bringing in consultants in order to make groups of firms capable of re-defining their collective interests so as to pave the way for what Sabel calls "studied trust" (Sabel 1992). But at the same time he warns us that this "does not prove that there is even one sure [...] way to actually extend trust when the actors believe it is in their interest to do so" (Sabel 1992). In addition, it is questionable if the intentional creation of trust between networking firms can be "embedded" in the same way as the original form of "mutual knowlegde and trust" found in Marshallian industrial districts. When it comes to the production of trust, agglomerations have two advantages. First, manufacturers do not only have to rely on their own experience but can exploit the experience of others. Secondly, agglomerations facilitate joint actions aiming at building up institutional trust (Humphrey and Schmitz 1996). In contrast to regional economic theory, Marshall 14 attaches a more independent role to agglomeration economies. The "Marshallian" view of the basic structures of industrial districts expresses the idea of "embeddedness" as a key analytical concept in understanding the workings of the districts (Granovetter 1985). It is precisely the embeddedness in broader socio-cultural factors, originating in pre-capitalist civil societies, that represents the material basis for Marshall's view of agglomeration economies as the specific territorial aspects of geographical agglomerated economic activity, which concern the quality of the social milieu of industrial districts, and which only indirectly affect the profits of firms. Among such factors, Marshall emphasises, in particular: the "mutual knowledge and trust" that reduces transaction costs in the local production system; the "industrial atmosphere" which facilitates the generation of skills (tacit knowledge) and (social) qualifications required by the local industry; and the effect of both these aspects in promoting (incremental) innovations and innovation diffusion among SMEs in industrial districts (Asheim 1994). By defining agglomeration economies as social and territorial embedded properties of an area, Marshall abandons "the pure logic of economic mechanisms and introduces a sociological approach in his analysis" (Dimou 1994, 27). Harrison emphasises that this mode of theorising is fundamentally different from the one found in conventional regional economics or in any other neoclassical-based agglomeration theory (Harrison 1991). A tentative answer to the problem of lack of extended trust in inter-firm networking may be found in the informal social barrier of loyalty (Hirschman 1970, Asheim 1990). A local community, or a community of professionals, characterised by the egalitarian and collective values of loyalty (not to be confused with solidaritiy) means higher barriers towards exit for its members, thus ensuring that the actors within, for example, an industrial agglomeration will continue to promote co-operation rather than competition for a longer period of time. This increases the effectiveness of voice, which "depends on the discovery of new ways of exerting influence and pressure towards recovery" (Hirschman 1970, 80). The discovery of such new ways of achieving improvement "from within" will usually be the result of the agency of either the most influential entrepreneurs or the professional, external experts (Asheim 1992). However, the importance of trust as a prerquisite to promote inter-firm co-opertion as a basis for competitiveness is not a guarantee in itself for a sufficient degree of innovativeness in the long run. Even so, factors such as trust among firms in the local cluster and loyalty among the workforce can be of great significance in forming close and innovative inter-firm networks with customers and suppliers/subcontracters as well as establishing flexible and learning intra-firm organisations, which are of strategic importance in fostering competitive advantage of firms and regions (i.e. Marshall’s agglomeration economies). On the other hand, as argued by Lundvall (1996), “it will not be possible to preserve a reasonable degree of trust without a minimum of social cohesion. As the social basis for learning is eroded, the rate of change will slow down. This is one reason why the analysis of the learning economy cannot neglect the social dimension and also why any policy strategy aiming at promoting the learning economy must have a New New Deal as an integrated part” (Lundvall 1996, 17). 15 Conclusion: Partnership as governance in Schumpetarian workfare states? What is the policy implications of the increased importance of co-operation in promoting innovation with regard to forms of governance in societies, in which non-economic factors play a significant role for their economic performance. According to Lundvall and Johnson (1994), post-Fordist societies are characterised by such an economy, which they call a learning economy. Jessop argues that “as the dominant techno-economic paradigm shifts from Fordism to post-Fordism, the primary economic functions of states are redefined” (Jessop1994, 262). He maintains that the post-Fordist changes in the organisation and location of production also make “public-private partnerships and other forms of heterarchy more relevant. ... This is seen in a turn from the “Keynesian welfare national state” to a more complex, negotiated system oriented to institutional competitiveness, innovation, flexibility, and “enterprise culture”. ... In the emerging Schumpetarian workfare regime, the market, the national state, and the mixed economy have lost significance to inter-firm networks, publicprivate partnerships, and a multilateral and heterarchic “negotiated economy”” (Jessop 1998, 35).9 Seen from a regional perspective, where local states during the Fordist era “operated as extensions of the central Keynesian welfare state” (Jessop1994, 271), we see today a “reorganisation of the local state as new forms of local partnership emerge to guide and promote the development of local resources. In this sense we can talk of a shift from local government to local governance. Thus local unions, local chambers of commerce, local venture capital, local education bodies, local research centres and local states may enter into arrangements to regenerate the local economy” (Jessop 1994, 272). This is a precise description of what we in this article, along with Ennals and Gustavsen (1999a), have called regional development coalitions, and which we regard as being of strategic importance for the formation of learning regions. Thus, from a Scandinavian point of view public-private partnerships, as an example of de-statization of politics, does contain some potential progressive elements of a policy of job-generating growth in Europe, and, could, consequently, rather be said to represent a continuity of “modernizing” social-democratic welfare states than the discontinuity of being a basic element of a Schumpetarian workfare state (Amin and Thomas 1996, Hernes 1978, Jessop 1994). This would be in line with the perspective of the recent Green Paper on “Partnership for a new organisation of work” from the European Commission DG V (Ennals and Gustavsen 1999a and 1999b, Fricke 1999, Totterdill 1999) as well as the overall popularity of the concept of learning regions among policy makers and several international agencies and organisations (in addition to DG V), such as the work of DG Regio of the European Commission on innovation policy and regional developement (Landabaso, forthcoming), and OECD’s series of European workshops on learning regions (e.g. Maskell and Törnqvist 1999). This is also in accordance 9 Porter (1998) argues that “leaders of business, government, and institutionss all have a stake – and a role to play – in the new economics of competition. ... The lines between public and private investment blur. Companies, no less than governments and universities, have a stake in education. Universities have a stake in the competitiveness of local businesses” (Porter 1998, 90). 16 with the new institutionalist perspective on regional development (Amin 1999, Amin and Thrift 1995b, Brulin 1998, Grabher 1993, Lundvall 1996). Finally, contrary to addressing the structural limits to learning in a capitalist economy, the focus should be on the new possibilities in a learning economy of creating context conditions supporting a plus sum game generating endogenous regional development in some regions without distorting the growth potentials of other regions (Lundvall 1996). Concerning the structural limits to learning, these are - within a capitalist economy - basically caused by a policy of weak competition. Thus, a policy of strong competition, building on innovation and differentiation strategies in networks of large and small firms on the basis of interactive, localised learning and continual innovation in industrial and territorial clusters, has considerable potential for learning, as it provides the best material context for an innovation based learning economy, and, as such, represents the most dynamic, long-term growth oriented kind of capitalism which can achieve development in as well as of regions. As mentioned earlier, the emphasis on interactive learning points to the importance of cooperation, which reminds us of the significance of non-economic factors, such as trust and institutions, for the economic performance of regions and nations. Consequently, the question of how trust can be fostered within firms, between firms in networks and by public-private partnership at the regional level in order to promote increased co-operation as a source of competitive advantage of regions, is very important from a policy perspective. According to Lazonick, “history shows that the driving force of successful capitalist development is not the perfection of the market mechanism but the building of organizational capabilities” (Lazonick 1991, 8). In general, according to Freeman and Perez (1986), it is important to remember that the diffusion (exploitation/utilisation) of knowledge is not dependent on techno-economic subsystems, but on the socio-institutional framework. Thus, in order to generate economic growth and increased employment, as a basis for achieving social cohesion, focus must be on the absorption capacity of socities, which points to the importance of non-economic factors such as culture (social capital) and politics (e.g. educational policies securing a well educated population through an equal, free of cost and proximate access to high quality educational facilities) for economic performance, through improving the potentials for (regional) learning in a society. However, a learning based strategy of endogenous regional development cannot be applied accross the board, as the necessary requirements concerning socio-cultural and socio-economic structures are to be found in relatively well-off regions, and the sufficient techno-economic and political insitutional structures only in relatively developed countries. In this context it is important not to have a pre-deterministic view of the development paths of capitalist societies. Marx gave up the paradigm of necessity in his political-economical works (Schanz 1985), implying that the "logic of capital" must be interpreted as tendencies, which depend on contingently related conditions to be realised (Asheim and Haraldsen 1991). Contemporary examples of economic development clearly show that the social democratic, coordinated capitalist development in Norway and the Third Italy is rather different from, and represent other "windows of opportunities" than, the neo-liberal, uncoordinated development in Britain and USA (Soskice 1999). This points to the duality of agency and structure in societal development, confirming that "men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past" (Marx 1972, 10). 17 This has to be taken into account when evaluating the prospects of a strategy for the formation of learning regions based on development coalitions in different regions, and the possible, resulting "worlds of production" (Storper and Salais 1997). References: Amin, A. (1999): An institutionalist perspective on regional development. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Amin, A. & N. Thrift (1995a): Territoriality in the global political economy. Nordisk Samhällsgeografisk Tidskrift, No. 20, 3-16. Amin, A. & N. Thrift (1995b): Institutional issues for the European regions: From markets and plans to socioeconomics and power of association. Economy and Society, 24, 41-66. Amin, A. & D. Thomas (1996): The negotiated economy: state and civic institutions in Denmark. Economy and Society, 25, 2, 255-281. Asheim, B. T. (1990): Innovation diffusion and small firms: between the agency of lifeworld and the structure of systems. In N. E. Alderman et al. (eds): Technological change in a spatial context: theory, empirical evidence and policy. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 37-55. Asheim, B. T. (1992): Flexible specialisation, industrial districts and small firms: A critical appraisal. In H. Ernste & V. Meier (eds): Regional development and contemporary industrial response. Extending flexible specialisation. Belhaven Press, London, 45-63. Asheim, B. T. (1994): Industrial districts, inter-firm co-operation and endogenous technological development: The experience of developed countries. In Technological dynamism in industrial districts: An alternative approach to industrialization in developing countries? Unctad, Unitied Nations, New York and Geneva, 91-142. Asheim, B. T. (1996): Industrial districts as "learning regions": A condition for prosperity? European Planning Studies, 4,4, 379-400. Asheim, B. T. (1997): ”Learning regions” in a globalised world economy: Towards a new competitive advantage of industrial districts? In S. Conti & M. Taylor (eds), Interdependent and uneven development: Global-local perspectives. Ashgate, Aldershot, 143-176. Asheim, B. T. (1999): TESA bedrifter på Jæren – fra et territorielt innovasjonsnettverk til funksjonelle konserndannelser? In A. Isaksen (ed), Regionale innovasjonssystemer. Innovasjon og læring i 10 regionale næringsmiljøer. STEP-report R-02, The STEP-group, Oslo, 131-152. Asheim, B. T. & T. Haraldsen (1991): Methodological and theoretical problems in economic geography. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 45,4, 189-200. 18 Asheim, B. T. & A. Isaksen (1997): Location, agglomeration and innovation: Towards regional innovation systems in Norway? European Planning Studies, 5,3, 299-330. Asheim, B. T. & G. K. Pedersen (1999): TESA - a development coalition within a learning region. In R. Ennals & B. Gustavsen (eds): Work organisation and Europe as a development coalition. Case studies. John Benjamin’s Publishing Company, Amsterdam-Philadelphia, 108-119. Asheim, B. T. & P. Cooke (1998): Localised innovation networks in a global economy: A comparative analysis of endogenous and exogenous regional development approaches. Comparative Social Research, Vol. 17, JAI Press, Stamford, CT, 199-240. Asheim, B. T. & P. Cooke (1999): Local learning and interactive innovation networks in a global economy. In E. Malecki & P. Oinäs (eds), Making connections. Ashgate, Aldershot, 145-178. Becattini, G. (1990): The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In F. Pyke et al. (eds): Industrial districts and inter-firm co-operationin Italy. International Institute for labour studies, Geneva, 37-51. Bellandi, M. (1989): The industrial district in Marshall. In E. Goodman & J. Bamford (eds): Small firms and industrial districts in Italy. Routledge, London, 136-152. Bianchi, P. (1996): New approaches to industrial policy at the local level. In F. Cossentino et al. (eds): Local and regional response to global pressure: The case of Italy and its industrial districts. Research Series 103, International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 195-206. Bonaccorsi, A. & A. Lipparini (1994): Strategic partnerships in new product development: An Italian case study. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11,2, 135-46. Brulin, G. (1998): How to shape creative territorial energy: The case of the Gnosjö Region. Concepts and Transformation, 3, 3, 255-269. Brusco, S. (1990): The idea of the industrial district: Its genesis. In F. Pyke et al. (eds): Industrial districts and inter-firm co-operation in Italy. International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 10-19. Brusco, S. (1996): Global systems and local systems. In F. Cossentino et al. (eds): Local and regional response to global pressure: The case of Italy and its industrial districts. Research Series 103, International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 145-158. Brusco, S. et al (1996): The evolution of industrial districts in Emilia-Romagna. In F. Cossentino et al. (eds): Local and regional response to global pressure: The case of Italy and its industrial districts. Research Series 103, International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 17-36. 19 Castells, M. (1996): The rise of the network society. Blackwell, Oxford. Castro, E. de & C. Jensen-Butler (1993): Flexibility, routine behaviour and the neo-classical model in the analysis of regional growth. Institute of Political Science, University of Aarhus. Cooke, P. (1994): The co-operative advantage of regions. Paper prepared for: Centenaire Harald Innis Centenary Celebration Conference on "Regions, Institutions, and Technology: Reorganizing Economic Geography in Canada and the Anglo-American World", University of Toronto, September. Dei Ottati, G. (1994): Cooperation and competition in the industrial district as an organization model. European Planning Studies, 2, 4, 463-83. Dimou, P. (1994): The industrial district: A stage of a diffuse industrialization process - the case of Roanne. European Planning Studies, 1,2, 23-38. Dosi, G. (1988): The nature of the innovative process. In G. Dosi et al. (eds): Technical change and economic theory. Pinter Publishers, London, 221-38. Ennals, R. & B. Gustavsen (1999a): Work organisation and Europe as a development coalition. John Benjamin’s Publishing Company, Amsterdam-Philadelphia. Ennals, R. & B. Gustavsen (1999b): Creating a new European development agenda: Learning across cultures. Concepts and Transformation, 4, 1, 11-21. Florida, R. (1995): Toward the learning region. Futures, 27,5, 527-536. Freeman, C. & C. Perez (1986): The diffusion of technical innovations and changes of techno-economic paradigm. Paper presented at the Conference on Innovation Diffusion. Venice, Italy, March 1986. Fricke, W. (1999): Editorial: Work organization, regional development and industrial democracy. Concepts and Transformation, 4, 1, 1-10. Gomes-Casseres, B. (1994): Group versus group: how alliance networks compete. Harvard Business Review, 72, 62-74. Grabher, G. (1993): Rediscovering the social in the economics of interfirm relations. In G. Grabher (ed): The embedded firm. On the socioeconomics of industrial networks. Routledge, London, 1-31. Granovetter, M. (1973): The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 6, 1360-80. Granovetter, M. (1985): Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 3, 481-510. 20 Greve, A. (1999): The role of social capital in the development of technology. Paper presented at a conference on ”Mobilizing knowledge in technology management: Competence construction in the strategizing and organizing of technical change”. Copenhagen, Denmark, October 1999. Haraldsen, T. (1994): Teknologi, økonomi og rom - en teoretisk analyse av relasjoner mellom industrielle og territorielle endringsprosesser. Doctoral dissertation, Department of social and economic geography, Lund University, Lund University Press, Lund. Harrison, B. (1991): Industrial districts: Old wine in new bottles? Working paper 90-35. School of urban and public affairs, Carnegie-Mellon University. Hassink, R. (1998): The paradox of interregional institutional learning. Science and Technology Policy Institute, Seoul, South Korea (mimeo). Hernes, G. (1978): Forhandlingsøkonomi og blandingsadministrasjon. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo. Herrigel, G. (1996): Crisis in German decentralised production: Unexpected rigidity and the challenge of an alternative form of flexible organization in Baden Württemberg. European Urban and Regional Studies, 3,1, 33-52. Hirschman, A. (1970). Exit, Voice and Loyalty. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. Howells, J. (1996): Regional systems of innovation? Paper presented at HCM Conference on “National systems of innovation or the globalisation of technology? Lessons for the public and business sector”, ISRDS-CNR, Rome, April. Hudson, R. (1999): The learning economy, the learning firm and the learning region: A sympathetic critique of the limits to learning. European Urban and Regional Studies, 6, 1, 5972. Humphrey, J & H. Schmitz (1996): Trust and Economic Development. Discussion paper No. 355, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. Håkansson, H. (1992): Corporate technological behaviour. Co-operation and networks. Routledge, London. Jessop, B. (1994): Post-Fordism and the State. In A. Amin (ed.): Post-Fordism. A reader. Blackwell, Oxford, 251-279. Jessop, B. (1998): The rise of governance and the risks of failure: the case of economic development. International Social Science Journal, No. 155, 29-45. Landabaso, M. (forthcoming): EU policy on innovation and regional development. Chapter 6 in Bakken, S. et al. (eds), Learning regions: Theory, policy and practice. 21 Lazonick, W. (1991): Business organization and the myth of the market economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Lazonick, W. (1993): Industry cluster versus global webs: Organizational capabilities in the American economy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 2, 1-24. Lazonick, W. & M. O'Sullivan (1995): Organization, finance and international competition. Industrial and Corporate Change, 4,4, 1-49. Lazonick, W. & M. O’Sullivan (1996): Sustained economic development. STEP Report No. 14, The STEP group, Oslo. Leborgne, D. & A. Lipietz (1992): Conceptual fallacies and open questions on post-Fordism. In M. Storper & A. J. Scott (eds): Pathways to industrialization and regional development. Routledge, London, 332-48. Lipparini, A. & G. Lorenzoni (1994): Strategic sourcing and organizational boundaries adjustment: A process-based perspective. Paper presented at the workshop on "The changing boundaries of the firm", European Management and Organisations in Transition (EMOT), European Science Foundation, Como, October. Lorenz, E. (1992): Trust, community, and cooperation: Toward a theory of industrial districts. In M. Storper & A. J. Scott (eds): Pathways to industrialization and regional development. Routledge, London, 195-204. Lundvall, B.-Å. (1992): Introduction. In B.-Å. Lundvall (ed.): National Systems of Innovation. Pinter Publishers, London, 1-19. Lundvall, B.-Å. (1996): The social dimension of the learning economy. DRUID Working Papers, No. 96-1, Aalborg University, Aalborg. Lundvall, B.-Å. & B. Johnson (1994): The learning economy. Journal of Industry Studies, 1,2, 23-42. Marx, K. (1972): The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in Marx, K. & F. Engels, Selected Works Volume 1, Progress Publishers, Moscow. Maskell, P. & G. Törnqvist (1999): Building a cross-border learning region. Copenhagen Business School Press, Copenhagen. Morgan, K. (1997): The learning region: Institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, Vol. 31, No. 5, 491-503. National Institute for Working Life (1997): Stronger partnership for learning regions. Stockholm. Nylehn, B. (1995): Kan "ledelse på norsk" være et konkurransefortrinn? Bedre Bedrift, nr. 3, 43-46. 22 Patchell, J. (1993): From production systems to learning systems: lessons from Japan. Environment and Planning A, Vol. 25, 797-815. Pedler, M. et al. (1991): The learning company. McGraw-Hill, London. Perroux, F. (1970): Note on the concept of "growth poles". In McKee, Dean & Leahy (eds): Regional economics: Theory and practice. The Free Press, New York, 93-103. Piore, M. & C. Sabel (1984): The second industrial divide: Possibilities for prosperity. Basic Books, New York. Porter, M. (1990): The competitive advantage of nations. Macmillan, London. Porter, M. (1998): Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, November-December, 77-90. Putnam, R. (1993): Making democracy work. Princeton University Press, Princeton. Pyke, F. (1994): Small firms, technical services and inter-firm cooperation. International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva. Pyke, F. & W. Sengenberger (1990): Introduction. In F. Pyke et al. (eds): Industrial districts and inter-firm co-operation in Italy. International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 1-9. Reich, R. (1991): The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21st-Century Capitalism. Knopf, New York. Rosenfeld, S. (1996): Does cooperation enhance competitiveness? Assessing the impacts of inter-firm collaboration. Research Policy, 25, 247-263. Sabel, C. (1992): Studied trust: Building new forms of co-operation in a volatile economy. In F. Pyke & W. Sengenberger (eds): Industrial districts and local economic regeneration. International Institute for Labour Studies, Geneva, 215-50. Sayer, A. (1992): Beyond Fordism and flexibility. In A. Sayer & R. Walker: The new social economy: rethinking the division of labor. Basil Blackwell, Boston, MA, 191-223. Schanz, H.-J. (1985): Marx og det moderne. Kurasje, No. 37, 3-14. Smith, K. (1994): New directions in research and technology policy: Identifying the key issues. STEP-report, No. 1, The STEP-group, Oslo. Soskice, D. (1999): Divergent production regimes: Uncoordinated and coordinated market economies in the 1980’s and 1990’s. In Kitchelt et al. (eds), Continuity and change in contemporary capitalism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 101-134. Storper, M. (1995a): Regional technology coalitions: An essential dimension of national 23 technology policy. Research Policy, 24, 895-911. Storper, M. (1995b): Competitiveness policy options: The technology - regions connection. Growth and Change, 26, 285-308. Storper, M. (1995c): The resurgence of regional economies, ten years later: The region as a nexus of untraded interdependencies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2,3, 191-221. Storper, M. (1997): The regional world. Territorial development in a global economy. The Guilford Press, New York and London. Storper, M. & R. Walker (1989): The capitalist imperative. Territory, technology, and industrial growth. Basil Blackwell, New York. Storper, M. & A. J. Scott (1995): The Wealth of Regions. Futures, 27,5, 505-526. Storper, M. & R. Salais (1997): Worlds of production. The action frameworks of the economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Totterdill, P. (1999): Workplace innovation as regional development. Concepts and Transformation, 4, 1, 23-43. Tödtling, F. (1995): Firm Strategies and Restructuring in a Globalised Economy. IIRDiscussion 53, Institute for Urban and Regional Studies, Wirtschaftsuniversität, Vienna. Weinstein, O. (1992): High technology and flexibility. In P. Cooke et al. (eds): Towards global localisation. UCL Press, London, 19-38. Woolcock, M. (1998): Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society, 151-208. You, J.-I. & F. Wilkinson (1994): Competition and co-operation: Toward understanding industrial districts. Review of Political Economy, 6,3, 259-278. 24