the full repsonse - Equality and Human Rights Commission

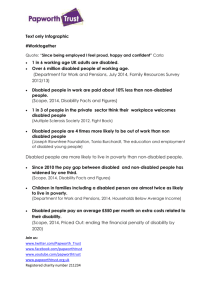

advertisement