Evidence and Interpretation

advertisement

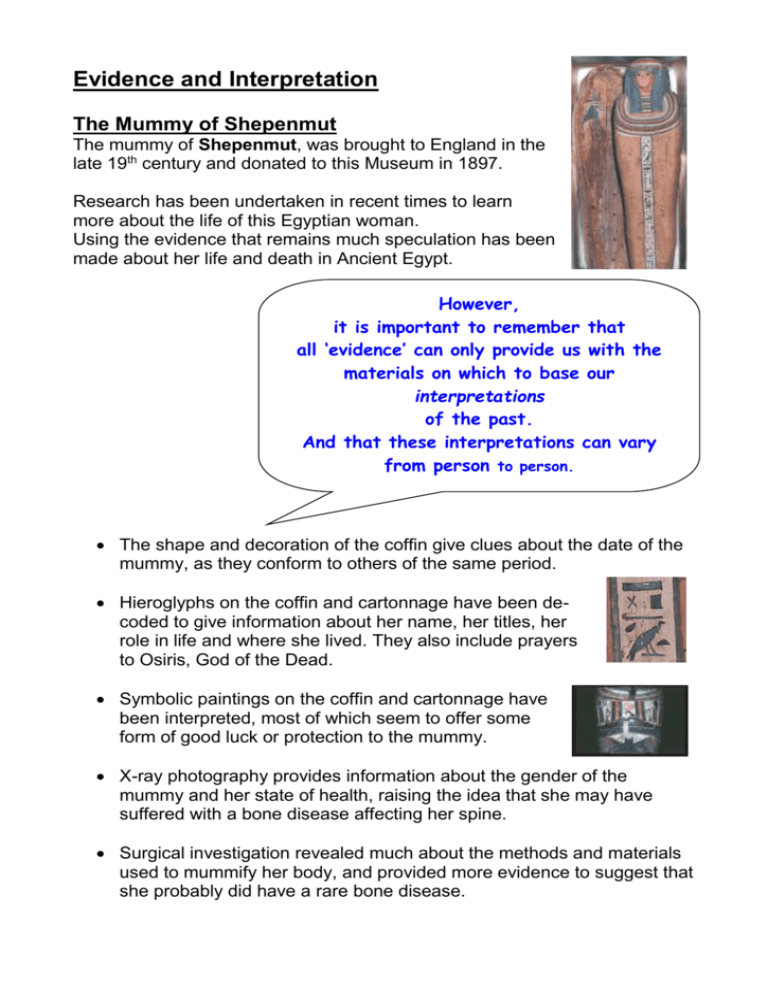

Evidence and Interpretation The Mummy of Shepenmut The mummy of Shepenmut, was brought to England in the late 19th century and donated to this Museum in 1897. Research has been undertaken in recent times to learn more about the life of this Egyptian woman. Using the evidence that remains much speculation has been made about her life and death in Ancient Egypt. However, it is important to remember that all ‘evidence’ can only provide us with the materials on which to base our interpretations of the past. And that these interpretations can vary from person to person. The shape and decoration of the coffin give clues about the date of the mummy, as they conform to others of the same period. Hieroglyphs on the coffin and cartonnage have been decoded to give information about her name, her titles, her role in life and where she lived. They also include prayers to Osiris, God of the Dead. Symbolic paintings on the coffin and cartonnage have been interpreted, most of which seem to offer some form of good luck or protection to the mummy. X-ray photography provides information about the gender of the mummy and her state of health, raising the idea that she may have suffered with a bone disease affecting her spine. Surgical investigation revealed much about the methods and materials used to mummify her body, and provided more evidence to suggest that she probably did have a rare bone disease. Research by C. V. Anthony Adams One researcher, C.V. Anthony Adams, based here at RAMM in the 1960’s, undertook much of this work. His findings have helped greatly in the interpretation of the symbolic paintings and hieroglyphs, and also informed us about the physical condition of the mummy. Extracts of his booklet ‘SHEPENMUT – PRIESTESS OF THEBES’ follow later. However, it must be remembered that these are only one person’s interpretations of the evidence! Other Interpretations . . . . Others have contested these interpretations, notably staff based at The British Museum in the 1980’s, saying that there is no evidence to suggest that Shepenmut had any special titles at all and may not have even been a priestess! Their research into the texts on the coffin suggests that: she was a ‘Lady of the House’ - i.e. a married woman her father Nes-Amenemipt, not her mother, was the ‘Carrier of the Milk Jar’ being a ‘Carrier of the Milk Jar’ was a low-grade profession equivalent to being a cow-herd there is no mention of the Temple of Amun there is no mention that she was a Priestess she and her father did come from Thebes, because of their names the coffins do date to the Third Intermediate Period, c.800 BC and that she was buried at Thebes They go on to mention that there was also a coffin listed in the Museum of Alexandria in 1904, that was almost certainly of the same date, belonging to a Lady of the House called Kharu who was daughter of the ‘Carrier of the Milk Jar’ Nes-Amenemipt, suggesting that she could possibly be the sister of Shepenmut. As a result of their research into the evidence, a letter from British Museum research staff to RAMM research staff suggests that the previous interpretation of the information was such because the researcher had: ‘picked out odd bits of information and melded them together to give a most misleading picture’! However, it is worth bearing in mind that their research was based purely on photographic evidence, having never seen the mummy face to face. Extracts from: - SHEPENMUT – PRIESTESS OF THEBES By C.V. Anthony Adams SHEPENMUT - Daughter of Esamenopet; Songstress of Amun-Re; Carrier of the Milk jar, and Priestess of the Temple of Thebes about 800 B.C., rests once more in the eternal sleep of death within her decorated cartonnage. She was the daughter of Esamenopet, and from the time when she was quite a young woman until the day of her death she would regularly shuffle her way along the burning sandy streets, going to and from the temple, while the heat of a remorseless sun beat down upon her body. Unlike our present-day nuns, Shepenmut was quite free to marry and have a family of her own if she so wished, but we have no evidence that she took advantage of this concession. We do know that about 800 B.C. she was a middle-aged woman, and that her life of dedication to the great god Amun-Re came to an end. In accordance with the custom and religious dictates of the time, her body was carefully mummified; placed in the beautifully decorated cartonnage case which was designed to represent the embalmed woman; having the facial area moulded in a state of peaceful resignation. The cartonnage was enclosed in a simple wooden coffin, and Shepenmut was laid to rest within the tomb, which had been prepared for her. So she remained undisturbed until the latter part of the nineteenth century when her tomb was discovered and her coffin, with its precious contents, was brought to England. Shepenmut had faithfully served the temple for many years, and naturally her death came as a great blow to her friends and relations. Indeed, while they mourned her passing, they were equally determined that she should receive the type of burial befitting her position as a priestess, but nevertheless such burials would only be equivalent to that of the average middleclass person of today. The religious teachings of several thousand years dictated that life after death depended upon the preservation of the body as the home to which the soul in due course might return. Such preservation varied in its technique with the passage of time, but we are concerned only with the process employed for Shepenmut. With great sorrow her body would be given into the custody of the embalmer's; the sorrow being all the more felt because Shepenmut would never be seen again by those who loved her, except as a mummy made ready for placing in the tomb. .... Apart from its mummiform shape, modeled face, wig, and decorated collar, the coffin of Shepenmut is much simplified and conforms to the designs of the late period. A single column of writing runs vertically down the lid; the text of which is a combination of prayers to Osiris, plus the titles of the priestess. These are also repeated along either side of the coffin. Within the coffin is a portrait of the goddess Isis, standing on the hieroglyph symbol of her sister goddess Nephthys. The arms of Isis are outstretched so as to enfold protectively the cartonnage containing the body of Shepenmut. The cartonnage case, or plaster and linen shell, covering the shrouded body is quite elaborate when compared with the plain coffin. Like the coffin, however, it is mummiform shape, and the decorations occupy four specific areas determined by four gaily coloured horizontal bands, and a vertical column of hieroglyphs. These symbolize the principal external bandages of the mummy, viz., a single band from head to foot and four horizontals. The blue wig is surmounted by a floral skullcap, beneath which protrude the wings of the protecting goddess Nekhbet. The lappets of the wig terminate in bands of yellow, and rest upon a beaded collar symbolic of a garland of assorted flowers. Immediately beneath the collar kneels the goddess Nephthys, wearing on her head the hieroglyph crown spelling her name, and her winged arms are outstretched in an attitude of protection across the mummy of Shepenmut. Coming now to the figures depicted between the first and second horizontal bands, the first at the extreme left is a standard on top of which is a Night Heron. This bird is symbolic of the resurrection from the dead of the god Osiris. The next figure is Hapy (Baboon-headed) who, with his brothers Imsety (Human-headed) next to him, and Qebhsenuef (Falcon-headed) and Duamutef (Dog-headed) at far right, constitute the four deities known as the Sons of Horus. It was their duty to guard the lungs, liver, intestines and stomach. Centrally in this same area is the hawk god, Horus, wearing on his head the sun disc of Amun. Horus also has his wings outstretched protectively across the priestess. On either side of Horus is a uraeus or serpent representing a goddess with different names who personified the burning Eye of Re, and who spits fire at enemies of the tombs. Each serpent wears upon its head the white crown or Mitre of Upper Egypt, and it is interesting to note that the serpent on the right has a signet ring or Shenu about its waist, offering 10,000,000 years of happiness to Shepenmut. In the next section are, at the left, the goddess Isis and on the right her sister Nepthys, each wears the sun disc of Amun and holds protective wings over the priestess. The central painting which now follows is an apron surmounted by plumes and sun disc of Amun. The exact significance of all such aprons is unknown, but on either side of it are found paintings of the god Horus in an attitude of protection; wearing the sun disc of Amun, and carrying a shenu in the claws. In the intervening spaces between the wings of the Horus gods and the apron are depicted two sacred rams representing power and prestige. Next comes the vertical strip of hieroglyphs, and to the extreme right of this is another standard. This time, however, it bears the symbol of the firestone and denotes strength. At the side of the standard is the figure of Shepenmut herself, with arms raised to greet her Father and Mother, who also welcome her from the left of this section. The remainder of the cartonnage, in the area of the feet, is given over to various symbols for the protection of the dead, and on the wooden base-board is painted a figure of the pied bull of Amenti. SURGERY ON SHEPENMUT Intensive X-ray examinations carried out on the mummy of Shepenmut revealed . . . . the appearance of opacification of the intervertebral discs with associated minimal osteo-arthritic changes which could suggest a diagnosis of ochronosis, a bone and joint sequela of alkaptonuria; an extremely rare disease caused by a Mendelian recessive gene, and which occurs once in about 10, 000, 000 individuals. Opacification of this type, however, might equally be the result of post-mortem chemical reaction on the spine, especially so if certain iron salts were present in the natron compound used for embalming. To resolve the problem it was decided to remove a section of vertebrae for biochemical analysis at University College Hospital, London. .... An operation of the type envisaged required considerable planning, since at virtually all stages it would be fraught with hitherto unencountered difficulties and dangers; the first of major importance involved the satisfactory opening of the cartonnage, and the second the prevention of the mummy collapsing during the many hours required for the operation. .... The priestess was enclosed in a double layer linen shroud, which had been drawn round the body and laced up the back with linen strips, the excess material at the head and feet tucked underneath to give a neat finish to the work. It is usual for a large figure of Osiris, God of the Dead, to be drawn in ink on the outer shroud, but in this instance it was omitted. From a purely scientific point of view the removal of the shroud revealed the actual mummy, the bandages at surface level being three inches wide and wrapped horizontally about the body. However, from an aesthetic point of view it would be more in keeping to state that for the first time in over 2, 700 years the eyes of man were privilged to see the mummy of Shepenmut, exactly as she was after the ancient Egyptian embalmers had completed their work on her. .... . . . . having carefully made an incision they found a beautifully-cast, three inch long wax figure of the jackal-headed god Duamutef and although its ears were missing, it indicated that the dissected material was probably the stomach……no other figurines were found…The pelvis was almost completely filled with a linen roll . . . . Having removed the section, and taken away samples of other materials such as fragments of viscera, resinous paste, inner bandage, etc. the operation, which had lasted four and half hours was complete and the work of restoration could begin. .... In life Shepenmut, as a priestess, contributed to the spiritual welfare of her people. In death, through the agency of her spine section, she not only provided comparative material for the study of Alkaptonuria, but the technique adopted for the operation on her was published in a special edition of the 'Medical News’ for the British Medical Association Annual Meeting. The BBC. made a film of the operation which was broadcast as an edited version on television in the ‘Tonight’ programme. Shepenmut has thus ensured that workers in the field of palaeopathology need no longer rely upon radiographs for evidence, since they can now follow a simple procedure which provides a large safety margin for the mummy, and also obtain specimens they require for study and research. Finally, a critical examination of Shepenmut's cartonnage case enabled us to evaluate its physical structure and reconstruct the carefully planned method its Egyptian makers used to ensure the survival of the mummy it was to contain. Taken from Discussions in Egyptology 16,1990 ISSN 0268-3083 Shepenmut – Priestess of Thebes, Her Mummification and Autopsy by C.V. Anthony Adams, F.R.E.S.