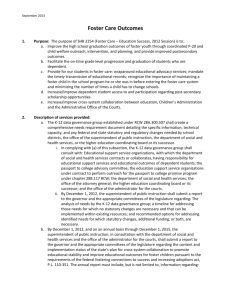

Empirical Review of Tables & Settings for Foster Care Visitation

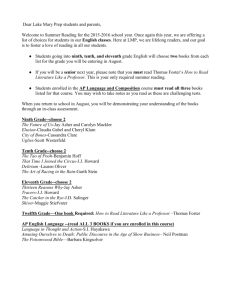

advertisement