Theoretical Explanations of Foreign Policy

advertisement

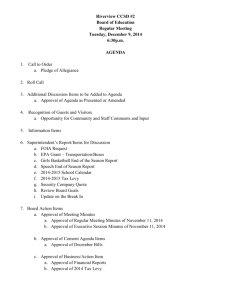

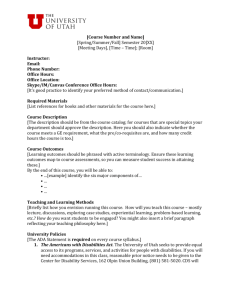

Political Science 530 Theoretical Explanations of Foreign Policy Spring 2012 Roy Licklider licklide@rci.rutgers.edu 732 932-9249 Our purpose in this course is to explore a variety of ideas about why states behave as they do. The approach is to try to isolate small groups of factors believed to be important, trace the theoretical assumptions about the circumstances under which they are expected to influence policy, and then look briefly at the best scholarship available to see whether in fact such relationships exist. Ideally we would have for each set of variables theoretical arguments, case studies (which are helpful in tracing relationships in detail), and cross-national quantitative analyses (to test the existence and power of relationships); in fact we are restricted by what research has been done and a limited amount of time. The following required books (all paperback) are available for purchase at the Rutgers University Bookstore: Valerie Hudson, Foreign Policy Analysis: Classic and Contemporary Theory G. John Ikenberry, American Foreign Policy: Theoretical Essays (Fifth Edition, 2005) Rose McDermott, Political Psychology in International Relations We will also be reading a substantial number of articles and book chapters, because much of the important theoretical and empirical work in foreign policy analysis has been published in this form. There will be no formal reading packet, but all of the articles will be available at the class Sakai site (https://sakai.rutgers.edu/portal). I have listed some suggestions for optional reading on the syllabus, but many more suggestions can be found in the 2010 syllabus of this course by Professor Levy; that syllabus is included on the Sakai site as well. A very long time ago I contemplated writing a textbook on comparative foreign policy. The project was never completed, but I did produce drafts of several chapters which I have resurrected from very deep storage and, perhaps in a fit of inappropriate vanity, have added to the syllabus. At least they are fairly short. Course Requirements: We will organize our weekly meetings as follows. We will usually begin with my own introductory comments on a particular body of literature, though in weeks of student presentations my own remarks will be briefer. We will then move to an open discussion of the material, including any student presentations. Most weeks we will cover several distinct topics, and we may have more than one presentation. For this system to work, and for students to benefit from it, each member of the seminar must complete all of the required reading prior to each class meeting and be prepared to discuss it. Each week I will try to provide some guidance as to what to emphasize in the following week’s reading. Given the different backgrounds and goals of different members of the seminar, I have adopted Professor Levy’s strategy of two alternative “tracks” or sets of requirements, a literature review track and a research track. You are free to select whichever track you prefer. I generally recommend, however, that IR majors planning to write a dissertation that involves some attention to how states formulate and implement their foreign policies (security, economic, human rights, environmental, etc.), especially those past their first year, write a research paper. I recommend that IR minors and those whose dissertation work is not likely to focus on how states formulate foreign policy adopt the literature review track. It is worth noting, however, that even a lot of system-level research includes a substantial foreign policy component, and that a case study of foreign policy making might nicely supplement a dissertation that employs a different methodology. 1) literature review track The basic requirement is a literature review paper . A electronic version of a full draft is due a week before an oral presentation in the class on the day that your subject is scheduled, as specified in the syllabus; it will be posted on Sakai and be part of the required reading for the class. The paper should be a 20-25 page (double space, with single space footnotes and references) critical review of the literature on a well-defined theoretical question relating to foreign policy analysis, often but not always equivalent to a sub-section of the syllabus. Whatever topic you choose, you must secure approval in advance, both to avoid misunderstandings and to facilitate the scheduling of presentations (see below). I would be happy to talk to you about what topics make most sense given your background and objectives in the program. The required and optional readings from the relevant section of the syllabus in many cases serve as a useful guide to the literature on any given topic, but please consult me for suggestions as to possible additions to the list (if the list on the syllabus is short) and/or priorities among them (if the number of items is quite large). Please do not assume that by reading all of the items in a particular section of the syllabus you have adequately covered a particular topic for your review. I also encourage you to incorporate material from other courses where relevant. In your literature review you should summarize the literature on your topic and at the same time organize it in some coherent way – preferably around a useful typology or theoretical theme, not around a succession of books and articles. You should note the theoretical questions that this literature attempts to answer, identify the key concepts and causal arguments, note some of the empirical research that bears on these theoretical propositions, and relate it to the broader literature on war and peace. You should identify the logical inconsistencies, broader analytical limitations, and unanswered questions of the leading scholarship in this area. You should also suggest fruitful areas for subsequent research. If you have any thoughts on how particular hypotheses could be tested, please elaborate on that. If you are uncertain as to what I am looking for in a critical review, I would be happy to make available a sample paper from a previous course. I expect rigorous analytical thinking that is well-grounded in the literature. You should include citations and a list of references. You may use either a "scientific" style (with parenthetical in-text citations) or a more traditional bibliographic style (as reflected in the Chicago Manual of Style), but just be consistent. See various journals for illustrations. Note that I want a separate bibliography even if a traditional footnoting style is used. I prefer footnotes to endnotes, but endnotes are also acceptable. The presentation based on each literature review will be scheduled for the day we discuss that topic in class. This is important, and it requires you to plan in advance, especially since the paper is due the week before the presentation. If you want to do a literature review on a topic that arises early in the term, you must get to work early. The formal part of the talk will be 12-15 minutes. You will then have the opportunity to respond to questions from the class for another half hour or so. I expect you to benefit from the feedback from class discussion and incorporate it into the final version of your paper, which is due in my mailbox May 7 at 2:00. There is no penalty for papers handed in within two weeks of that date, but papers handed in even a day late might receive an incomplete, given deadlines for handing in grades. 2) Research paper track. The requirement here is variable, depending on the stage of a student's work on a project. If you are just starting on a research project, a research design will be sufficient, but if you have been working on a particular project for a while I expect you to implement the research design and carry out the empirical research. If your paper for the class is a research design, I expect you to identify the question you are trying to answer, ground it in the theoretical literature and in competing analytical approaches, specify your key hypotheses, offer a theoretical explanation for those hypotheses, and provide a detailed statement as to how you would carry out the research. This includes the specification of the dependent and independent variables and the form of the relationship between them, the operationalization of the variables, the identification (and theoretical justification) of the empirical domain of the study (i.e., case selection), the identification of alternative explanations for the phenomenon in question, and an acknowledgment of what kinds of evidence would confirm your hypotheses and what kinds of evidence would disconfirm or falsify your hypotheses. Try to do this in 20-25 pages. And please consult with me along the way. Submitting an outline along the way would be helpful. You should understand that I have high standards for the research designs. I think of them as roughly equivalent to rough drafts of dissertation proposals or grant proposals. As to your presentation based on the research, consult with me, but in most cases I prefer that you emphasize (in the presentation) the theoretical argument and the research design phase of the project rather than your findings. We will schedule these presentations for late in the term, though if it fits earlier and if you are ready at that time we could go earlier (which would be a good way for you to get feedback on your project). Note that while I am quite tolerant of incompletes for research papers, I still expect a presentation of the theory and research design during the term. Research papers are more elaborate and involve a lot more work, but presumably Ph.D. students enroll in the program because this is what they want to do. There is no set length for a research paper, but one guideline is about 35-40 pages, which is the outer limit for most journal submissions. Please double space the text and single space the footnotes and references and submit an electronic copy to me a week before the presentation so I can post in on Sakai for the class to read. I am generally quite open to very different methodological perspectives, the norms of mainstream IR favor research that aims to construct and test falsifiable (loosely defined) hypotheses about foreign policy or international behavior, or to construct interpretations of particular episodes and then support those interpretations with empirical evidence. I share these norms, and I am unenthusiastic about theoretical arguments about the empirical world for which there is no conceivable evidence that would lead to their rejection. At the same time, I recognize the value some research communities place on formal theory construction independent of empirical test, or on radical constructivist critiques without systematic empirical analysis, and I would be willing to discuss the possibility of papers along these lines. Paper (literature and research review) Due Dates: May 7, 2:00, in my mailbox; email is appropriate only if absolutely necessary Grading The point of a seminar, as opposed to just being given a reading list, is to participate in and learn from class discussion of the reading. This requires all of us to read the assigned material in advance with some care, and it is often useful to take written notes on it as well. Life often makes this inconvenient so I have structured institutions to shape expectations and behaviors in such circumstances. 20% READING QUIZZES: Each session will begin with a short reading quiz—three questions about one of the assigned readings for that day. Students will have 5-10 minutes to answer them, and you may use your own written notes (but nothing on computers for obvious reasons). The quizzes are graded pass/fail—satisfactory answers to two questions are a pass. We have fourteen sessions scheduled. Students who pass 11 of the 14 quizzes will receive an A for that part of the course, students who pass 10 will receive a B, etc. There will be no final exam. 20% CLASS PARTICIPATION: Since the whole point of discussion is to help your classmates, at the end of the semester each students will assign a letter grade to every other student’s class participation. The average of these grades will count half of the total participation grade; I will independently assign a participation grade for the other half. 10% CRITIQUES: Everyone doing a presentation (literature or research) is required to submit a full draft of the paper a week in advance for distribution to the class as required reading. Everyone else in the class is required to prepare a brief (2-3 page) written critique of the paper and bring two copies to class, one for the author and one for me. I do not grade the draft, but I do grade the critiques; the criterion is how much you have made helpful suggestions to improve the quality of the draft. Broader rather than narrow comments are encouraged; do not simply check grammar and spelling! 50%: PAPER GRADE 1. THEORETICAL INTRODUCTION (1/19/12) Roy Licklider, “How Do We Know What We Know?” Kenneth Waltz, Man, the State, and War, chapter 1 J. David Singer, “The Level-of-Analysis Problem in International Politics” in James N. Rosenau, International Politics and Foreign Policy (1969), chapter 7. Hudson, chapter 1 Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (1976), chapter 1 G. John Ikenberry et. al., “Introduction: Approaches to Explaining American Foreign Economic Policy,” International Organization, 41, 1 (Winter 1988), 1-14 Ikenberry, Introduction and part 1, chapter 1 (Holsti) Walter Carlsnaes, “Foreign Policy” in Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse, and Beth A. Simmons, eds., Handbook of International Relations (2002), 331-349 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus sections 1 and 2 2. SYSTEMIC EXPLANATIONS (1/26/12) Hudson, pp. 153-162 Roy Licklider, “The Effects of the International System on Foreign Policy of Individual States” Ikenberry, part 2, chapter 1 (Waltz) and part 8, chapters 1-4 (Huntington; Krauthammer; Ikenberry; Jervis) Lars-Erik Cederman et. al., “Testing Clausewitz: Nationalism, Mass Mobilization and the Severity of War,” International Organization, 65 (October 2011), 605-638 Steven Pinker, “A History of Violence,” New Republic, 236, 12 (March 19, 2007), 18-21 Douglas Lemke, “The Continuation of History: Power Transition Theory and the End of the Cold War,” Journal of Peace Research, 34 (February 1997), 23-36 Ann Florini, “The Evolution of International Norms,” International Studies Quarterly, 40 (1996), 363-389 Stefan Fritsch, “Technology and Global Affairs,” International Studies Perspectives, 12, 1 (February 2011), 27-45 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 3 (also relevant for External Explanations) Elizabeth Fausett and Thomas J. Volgy, “Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs) and Interstate Conflict: Parsing Out IGO Effects for Alternative Dimensions of Conflict in Postcommunist Space,” International Studies Quarterly, 54, 1 (March 2010), 79-101 Brian Greenhill, “The Company You Keep: International Socialization and the Diffusion of Human Rights Norms,” International Studies Quarterly, 54, 1 (March 2010), 127-145 Derick Becker, “The New Legitimacy and International Legitimation: Civilization and South African Foreign Policy,” Foreign Policy Analysis, 6, 2 (April 2010), 133-146 3. EXTERNAL EXPLANATIONS (2/2/12) Roy Licklider, “External Variables: How Does One State Influence Another’s Foreign Policy?” Ikenberry, part 2, chapter 3 (Ikenberry) and pp. 402-413 (Allison) Roy Licklider, “The Power of Oil: The Arab Oil Weapon and the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the United States,” International Studies Quarterly, 32, 2 (June, 1988), 205-226 Peter Viggo Jakobsen, “Pushing the Limits of Military Coercion Theory,” International Studies Perspectives, 12, 2 (May 2011), 153-170 Douglas M. Stinnett et. al., “Complying By Denying: Explaining Why States Develop Nonproliferation Export Controls,” International Studies Perspectives, 12, 3 (August 2011), 308-326 Kenneth A. Schultz, “The Enforcement Problem in Coercive Bargaining: Interstate Conflict over Rebel Support in Civil Wars,” International Organization, 64, 4 (2010), 281-312 Miroslav Nitide, “Getting What You Want: Positive Inducements in International Relations,” International Security, 35, 1 (Summer 2010), 138-183. Valentin Krustev, “Strategic Demands, Credible Threats, and Economic Coercion Outcomes,” International Studies Quarterly, 54, 1 (March 2010), 147-174 OPTIONAL: Alexander George et. al., The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy Wallace Thies, When Government Collide: Coercion and Diplomacy in the Vietnam Conflict, 1964-1968, pp. 284-348 Roy Licklider, Political Power and the Arab Oil Weapon: The Experience of Five Industrial Nations (1988) Barry Blechman and Stephen S. Kaplan, Force without War: U.S. Armed Force as a Political Instrument Stephen S. Kaplan, Diplomacy of Power: Soviet Armed Forces as a Political Instrument Todd Sechser, “Goliath’s Curse: Coercive Threats and Asymmetric Power,” International Organization, 64, 4 (2010), 627-660 Michael Allen and Benjamin Fordham, “From Melos to Baghdad: Explaining Resistance to Militarized Challenges from More Powerful States,” International Studies Quarterly, 55, 4 (December 2011), 1025-1045 Levy 2010 syllabus, part 3 (also relevant to Systemic Explanations) 4. SOCIETAL EXPLANATIONS I (2/9/12) SIZE (POWER) Roy Licklider, “Societal Variables: Size and Power Capabilities” Hudson, pp. 143-153 Laura Neack, The New Foreign Policy: Power Seeking in a Globalized Era, chapters 8-9 Andrew J. R. Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics, 27 (January, 1975), 175-200. David A. Cooper, “Challenging Contemporary Notions of Middle Power Influence: Implications of the Proliferation Security Initiative for ‘Middle Power Theory,’” Foreign Policy Analysis, 7, 3 (July 2011), 317-336 DEVELOPMENT Roy Licklider, “Economic Development and Modernization” Mohammed Ayoob, “The Security Problematic of the Third World,” World Politics, 43 (January 1991), 257-283 Jack Levy and Michael Barnett, “Alliance Formation, Domestic Political Economy, and Third World Security,” Jerusalem Journal of International Relations, 14 (December 1992) Robert Rothstein, “National Security, Domestic Resource Constraints, and Elite Choices in the Third World” in S. Deger and R. West, Defense, Security and Development Jeff Colgan, “Oil and Revolutionary Governments: Fuel for International Conflict,” International Organization, 64, 4 (2010), 661-694 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 4k Maurice A. East, Size and Foreign Policy Behavior: A Test of Two Models, World Politics, 25 (July, 1973), 555-576. Jeanne A. K. Hay, Small States in World Politics: Explaining Foreign Policy Behavior Andrew Cooper and Timothy Shaw, The Diplomacies of Small States: Between Vulnerability and Resilience (2009) The Foreign Policy Power of Small States, special issue of Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 23 (September 2010), 381-453 John Scott Masker, Small States and Security Regimes: The International Politics Of Nuclear Non-Proliferation in Nordic Europe and the South Pacific Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner, Small States in Global Affairs: The Foreign Policies of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) 5. SOCIETAL EXPLANATIONS II (2/16/12) CULTURE Hudson, chapter 4 Judith Goldstein and Robert Keohane, “Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytic Framework” in Goldstein and Keohane, Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions and Political Change (1993), chapter 1 Ikenberry, part 4 chapters 1 (Huntington) and 4 (Keohane) Fritz Gaenslen, “Culture and Decision Making in China, Japan, Russia, and the United States,” World Politics, 39, 1 (October 1986), 78-103 Jeffrey W. Legro, "Which Norms Matter? Revisiting the 'Failure' of Internationalism." International Organization, 51/1 (Winter 1997), 31-64. Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, “Taking Stock: The Constructivist Research Program in International Relations and Comparative Politics,” Annual Review of Political Science, 4 (2001), 391-416 Peter Katzenstein, The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics (1996), chapters 1 (Katzenstein) and 2 (Jepperson et. al.) Steve Smith, “Foreign Policy Is What States Make of It: Social Construction and International Relations Theory” in Vendulka Kubalkova, Foreign Policy in a Constructed World (2001) Lisa Ann Richey, “In Search of Feminist Foreign Policy: Gender, Development, and Danish State Identity,” Cooperation and Conflict, 36, 2 (June 2001), 177-212 Carolyn M. Warner and Stephen G. Walker, “Thinking about the Role of Religion in Foreign Policy: A Framework for Analysis,” Foreign Policy Analysis, 7, 1 (January 2011), 113-135. OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 8 6. SOCIETAL EXPLANATIONS III IDEOLOGY AND CLASS (2/23/12) Ikenberry, part 3, chapters 1-3 (Frieden; Bacevich; Wade X (George Kennan), The Sources of Soviet Conduct, Foreign Affairs, 25, 4 (July, 1947), pp. 566-582 (18) Thomas E. Weisskopf, “Capitalism, Socialism, and the Sources of Imperialism” in G. John Ikenberry, American Foreign Policy (Scott, Foresman, 1989— not the text), 162-185. Jerome Slater and Terry Nardin, “The Concept of a Military-Industrial Complex” in Steven Rosen, Testing the Theory of the Military-Industrial Complex (1973), chapter 2 Kevin Narizny, “Both Guns and Butter, or Neither: Class Interests in the Political Economy of Rearmament,” American Political Science Review, 97, 2 (May 2003), 203-220 Jerome Slater, "Two Books of Mearsheimer and Walt." Security Studies, 18, 1 (2009): 4-30 (remainder is optional). OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, parts 7a, 7b, and 8b 7. GOVERNMENTAL EXPLANATIONS-ACCOUNTABILITY I (3/1/12) Hudson, chapter 5 John Owen, “How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace,” International Security, 19, 2 (Autumn 1994), 87-125 Bruce Bueno de Mesquita et. al., “An Institutional Explanation of the Democratic Peace,” American Political Science Review, 93, 4 (December 1999), 791807 Kenneth A. Schultz, Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy (2001), chapters 1-3 Jun Koga, “Where Do Third Parties Intervene? Third Parties’ Domestic Institutions and Military Interventions in Civil Conflicts,” International Studies Quarterly, 55, 4 (December 2011), 1143-1166 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 6a-c 8. GOVERNMENTAL EXPLANATIONS: ACCOUNTABILITY II (3/8/12) Ikenberry, part 5, chapters 1-4 (Roskin; George; Jacobs and Page; Trubowitz) Ole R. Holsti, “Public Opinion and Foreign Policy: Challenges to the AlmondLippmann Consensus,” International Studies Quarterly, 36, 4 (December 1992), 439-466 Jack Levy, “The Diversionary Theory of War: A Critique” in Manus Midlarsky, Handbook of War Studies (1989), chapter 11 Jack Levy and William Mabe, “Politically Motivated Opposition to War,” International Studies Review, 6 (2004), 65-83 Jack Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (1991), chapters 1, 2, & 8 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 6d-g 9. GOVERNMENTAL EXPLANATIONS-BUREAUCRACY I (3/22/12) Ikenberry, part 6, chapters 1-2 (Allison; Krasner) Morton Halperin and Arnold Kanter, “The Bureaucratic Perspective: A Preliminary Framework” in Halperin and Kanter, Bureaucratic Politics and Foreign Policy (1974), 1-42 John Steinbruner, The Cybernetic Theory of Decision (1976), chapter 3 James C. Thomson, “How Vietnam Happened” in Morton Halperin and Arnold Kanter, Readings in American Foreign Policy (1973), 98-110 Jack Levy, “Organizational Routines and the Causes of War,” International Studies Quarterly, 30 (June 1986), 193-222 Stuart J. Kaufman, “Organizational Politics and Change in Soviet Military Policy,” World Politics, 46, 3 (April 1994), 355-382 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 4a-h 10. GOVERNMENTAL EXPLANATIONS: BUREAUCRACY II (3/29/12) Robert J. Art, “Bureaucratic Politics and American Foreign Policy: A Critique,” Policy Sciences, 4 (1973), 467-490 Jonathan Bender and Thomas H. Hammond, “Rethinking Allison’s Models,” American Political Science Review, 86 (June 1992), 301-322 Alexander George, “The Case for Multiple Advocacy in Making Foreign Policy,” American Political Science Review, 66 (September 1972), 751-785 Margaret G. Hermann, “How Decision Units Shape Foreign Policy: A Theoretical Framework,” International Studies Review, 3, 2 (Summer 2001), 47-82 Helen V. Milner, “Rationalizing Politics: The Emerging Synthesis of International, American, and Comparative Politics,” International Organization, 52, 4 (Autumn 1998), 759-786 Ronald Rogowski, “Institutions as Constraints on Strategic Choice” in David A. Lake and Robert Powell, Strategic Choice and International Relations (1999), 116-136 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, parts 4i-j and 5 11. GOVERNMENTAL EXPLANATIONS: SMALL GROUPS (4/5/12) Hudson, chapter 3 (38) McDermott, chapter 9 Eric K. Stern, “Probing the Plausibility of Newgroup Syndrome: Kennedy and the Bay of Pigs” in Paul ‘t Hart et. al., Beyond Groupthink: Political Group Dynamics and Foreign Policy-making (1997), chapter 6 Philip E. Tetlock et. al., “Assessing Political Group Dynamics: A Test of the Groupthink Model,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63 (September 1992), 403-425 Dina Badie, “Groupthink, Iraq, and the War on Terror: Explaining US Policy Shift toward Iraq,” Foreign Policy Analysis, 6, 4 (October 2010), 277-296 Margaret G. Hermann et. al., “Who Leads Matters: The Effects of Powerful Individuals”, International Studies Review, 3, 2 (Summer 2001), 83-132 David G. Myers and Helmut Lamm, “The Group Polarization Phenomenon,” Psychological Bulletin, 83, 4 (1976), 605-627 Thomas Preston, “Presidential Personality and Leadership Style” in Preston, The President and His Inner Circle: Leadership Style and the Advisory Process in Foreign Affairs, chapter 1 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, part 11 12. INDIVIDUAL EXPLANATIONS I (4/12/12) Hudson, chapter 2 McDermott, chapters 1-3 and 10 INFORMATION PROCESSING: COGNITION, BELIEFS AND IMAGES Ikenberry, part 7, chapters 1-3 (Jervis; Tetlock and McGuire; Khong) OPTIONAL: McDermott, chapters 4-5 OPERATIONAL CODE Stephen G. Walker, “Operational Code Analysis as a Scientific Research Program: A Cautionary Tale” in Colin Elman and Miriam Fendius Elman, Progress in International Relations Theory: Appraising the Field (2003), 245-276 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, parts 9a-e 13. INDIVIDUAL EXPLANATIONS II (4/19/12) EMOTIONS AND MOTIVATIONS McDermott, chapter 6 MODELS OF LEARNING Lisa R. Anderson and Charles A. Holt, “Classroom Games: Understanding Bayes’ Rule,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 4 (Spring 1996), 179-187 Robert Jervis, “How Decision-Makers Learn from History” in Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (1976), chapter 6 Jack Levy, “Learning and Foreign Policy: Sweeping a Conceptual Minefield,” International Organization 48 (Spring 1994), 279-312 PERSONALITY: PSYCHOBIOGRAPHY McDermott, chapter 7 Ikenberry, part 7, chapter 4 (Winter et. al.) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP McDermott, chapter 8 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, parts 9f and 10 14. INDIVIDUAL EXPLANATIONS III (4/26/12) THREAT PERCEPTON AND INTELLIGENCE FAILURES Robert Jervis, “Perceiving and Coping with Threat” in Jervis et. al., Psychology and Deterrence (1985), chapter 2 Avi Shlaim, “Failures in National Intelligence Estimates: The Case of the Yom Kippur War,” World Politics, 28 (1976), 348-380 HEURISTICS AND BIASES Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and biases” in Daniel Kahneman et. al., Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (1982), chapter 9 PROSPECT THEORY Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “Rational Choice and the Framing of Decisions,” Journal of Business, 59 (4/2 (1986), S251-278 Jack S. Levy, “Prospect Theory, Rational Choice and International Relations,” International Studies Quarterly, 41/1 (March 1997), 87-112 SUNK COSTS AND MODELS OF ENTRAPMENT Barry M. Staw and Jerry Ross, “Behavior in Escalation Situations: Antecedents, Prototypes, and Solutions,” Research in Organizational Behavior, 9 (1987), 39-78 TIME HORIZONS AND INTERTEMPORAL CHOICES Philip Streich and Jack S. Levy, “Time Horizons, Discounting, and Intertemporal Choice,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51, 2 (April 2007), 199-226 OPTIONAL: Levy 2010 syllabus, parts 11f-g and 12