PlaneDebate Packet 238 - Cross

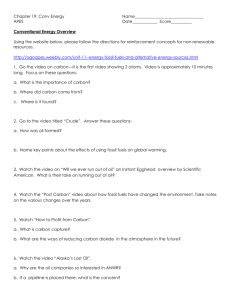

advertisement