COMPARATIVE SYNTAX OF FIJIAN AND TONGAN

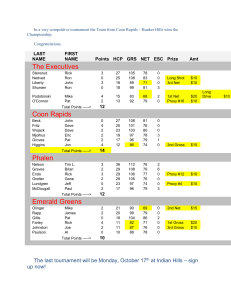

advertisement