56-JSC-A634

advertisement

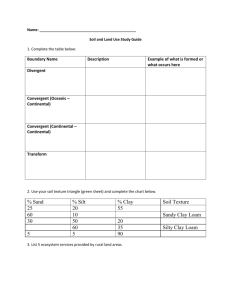

1 ELIMINATING UNCERTAINTY ASSOCIATED WITH CLASSIFYING SOIL TYPES IN DISTRIBUTED HYDROLOGIC MODELING HAPUARACHCHIGE P. HAPUARACHCHI, ANTHONY S. KIEM, HIROSHI ISHIDAIRA, JUN MAGOME and KUNIYOSHI TAKEUCHI Takeuchi-Ishidaira Lab., Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, Yamanashi University, Takeda 4-3-11, Kofu, Yamanashi 400-8511, JAPAN This paper presents a method to estimate the parameter values associated with soil characteristics in a distributed hydrologic model. The new approach accounts for all soil types in a catchment, regardless of the number of soil types present, eliminating the need for subjective soil reclassification methods and more accurately approximating the true physical characteristics of the catchment. The hydrologic model parameter values corresponding to soil type are calculated as a function of the amount (%) of basic soil types (sand, silt and clay) within each sub unit (e.g., grid, hydrological response unit or sub catchment) based on three coefficients (which represent the actual parameter value for sand, silt and clay respectively). The three coefficients can be determined based on either field measurements or by calibration (or in the case of ungauged catchments by transferring coefficient values previously determined in other similar catchments). The current study uses the new method in the BTOPMC model (block-wise use of TOPMODEL with Muskingum-Cunge flow routing method) to estimate lateral transmissivity (T0). The results indicate that the performance of distributed hydrologic models can be improved using the new method and that reclassifying or grouping soil types so that the effects of soil on hydrologic processes can be modeled is a significant and unnecessary source of uncertainty that can be eliminated. INTRODUCTION The impact of soil type on the basic hydrological behaviors of a catchment is an important factor in distributed hydrologic modeling. However in any catchment, numerous different types of soil can be present making reclassification of soil type difficult and some times unrealistic. In a distributed hydrologic model, it is difficult to incorporate different parameter values for each soil type due to the large amounts of data and calculations required to estimate such a large number of parameters. Therefore in many applications, only the dominating soil types present in the catchment are identified and the minor types are incorporated into these dominating classes considering their similar properties. Thus a great deal of subjectivity and uncertainty is inevitable in these reclassification methods since it is hard to determine exactly which soil types have similar properties (e.g., is sandy clay more similar to clay or sand and what criteria are used to decide). 2 This paper presents a method to estimate the parameter values associated with soil characteristics in a distributed hydrologic model. In the new approach, hydrologic model parameter values corresponding to soil type are calculated as a function of the amount (%) of basic soil types (sand, silt and clay) within each sub unit (e.g., grid, hydrological response unit or sub catchment) based on three coefficients (which represent the actual parameter value for sand, silt and clay respectively) that can be determined based on either field measurements or by calibration. Consequently, the actual soil texture of each sub-unit is uniquely considered and this is achieved through the estimation of only three coefficients – note that the number of coefficients to be determined is always three regardless of the heterogeneity of soil present in any study catchment. In addition, this new approach can effectively be adopted to reduce uncertainty in model predictions for both gauged and ungauged catchments. BTOPMC MODEL The BTOPMC (Block-wise use of TOPMODEL with Muskingum-Cunge flow routing method) is a grid based semi distributed hydrological model developed at the University of Yamanashi (Japan) for hydrological simulations in large river basins (Takeuchi et al., [6]; Ao et al., [1]). To facilitate the application of the model in large river basins, the total basin area is automatically subdivided into natural sub-basins by the Pfafstetter numbering system (Verdin and Verdin, [8]). The three dimensional physiographic heterogeneity of the basin is considered in the model mutually in terms of topography, soil types, geology, vegetation cover, and rooting depth. Basically the soil column is divided into three layers as root zone, unsaturated zone and the saturated zone. The non uniformity of the root zone depth over the catchment is taken into account using the distribution and the type of vegetation. In the model, runoff generation is based on the TOPMODEL (Beven and Kirkby, [2]; Beven and Binley, [3]; Quinn et al., [5]) concepts and flow routing is carried out by the Muskingum-Cunge method. The model parameters (Table 1) are calibrated either manually or automatically using the SCE-UA algorithm (Duan et al., [4]). The inputs of the model are land cover map, digital elevation model (DEM), soil map, precipitation, and evaporation data. It is possible to obtain the hydrologic characteristics (e.g., depth to the water table, actual evaporation, overland flow, base flow etc.) of any location (grid cell) of the catchment as the model output. Table 1. Parameters of the BTOPMC model Description Block average Manning's coefficient Decay factor of lateral transmissivity Average saturation deficit Lateral transmissivity under saturated conditions Maximum root zone capacity Parameter n0 m S0 T0 Srmax Units m m m2/h m 3 METHODOLOGY In the BTOPMC model, the lateral transmissivity (T0) of soil is used to calculate the base flow and it is one of the model parameters that has to be calibrated. Traditionally, it is assumed that the soil properties in a sub-catchment are homogeneous and a fixed T0 value is assigned to every grid cell in the sub-catchment. However it is clear that this assumption is not realistic, especially when considering a large catchment area. In order to incorporate the actual soil properties of each grid cell in the calculation of base flow, the T0 value was assigned to each grid cell based on the dominant soil type present. It was observed that the model performance could be improved significantly using this method. However, the uncertainty associated with soil classification is inevitable. For example, if the grid cell contains nearly equal percentages of sand, silt and clay, it is hard to determine the dominating soil type. Therefore, in order to incorporate the effect of actual soil properties in the T0 value regardless of the number of soil types present in the catchment, the following method is proposed. The value of T0 for each grid cell is calculated using the following equation. T0 U clay T0 Clay U sand T0 sand U silt T0 silt (1) Where Ucaly, Usand, and Usilt are the percentages of clay, sand, and silt present in each grid. It is assumed that the soil texture in a grid cell is homogeneous and the sum of Ucaly, Usand, and Usilt is 1. T0 clay, T0 sand, T0 silt are parameters which represent the other soil textural properties (particle size, pore size etc.) present in the catchment. In other words, T0 clay represents the T0 value of a particular soil column which only consists of clay. Usually these three parameter values are calibrated in the model. The basic advantage of the new approach is the number of coefficients to be determined is always three regardless of the heterogeneity of soil present in any study catchment and the actual soil texture of each sub-unit (e.g., grid, hydrological response unit) is uniquely considered. DATA AND APPLICATION In the present study the BTOPMC model is applied to the Mekong River basin (Figure 1) for simulating the river flow at two discharge gauging stations, Pakse and Mukdahan. The Mekong River is the longest river in southeastern Asia. It starts from the Qinghai province in China and crosses Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam and flows to the South China Sea passing 4200 km. The Mekong Basin population is about 60 Million and many of them directly or indirectly depend on the river. The annual average precipitation of the basin is about 1570 mm and the upstream drainage area of Pakse and Mukdahan are 545000, and 391000 km2 respectively (UNESCO, [7]). In this study, the new method (Eq. 1) is used to calculate the T0 value in the BTOPMC model and the result is compared with the normal application where the T0 4 value is based on the dominating soil type in each grid. The hydrological data from 1972 to 1977 is used for calibrating the model (daily time step) and from 1978 to 1985 for validating the model. The model is calibrated using the observed discharge at Pakse and validated at both Pakse and Mukdahan discharge gauging stations. The precipitation measured at 64 gauging stations over the catchment is used (from the Mekong River Commission and the China Meteorological Administration and Chinese Academy of Sciences). The monthly average potential evaporation is calculated using the PenmanMonteith method for each grid (Zhou et al., [9]). The digital elevation model for the basin is generated from the USGS 30 arc second GTOPO30 data set. 100°0'0"E 110°0'0"E Legend ! ! ! ! $ Discharge Gauging Stations ! Precipitation Gauging Stations ! ! China 30°0'0"N 30°0'0"N ! ± ! ! ! ! ! ! Mekong Basin ! India ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20°0'0"N 20°0'0"N ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mukdahan ! ! ! ! ! $! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Pakse ! ! ! $ 0 1 2 4 6 10°0'0"N 10°0'0"N ! 8 Decimal Degrees 100°0'0"E 110°0'0"E Figure 1. Location of the Mekong River basin and the discharge and precipitation gauging stations The IGBP (International Geosphere Biosphere Program) land cover and the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) soil map are used in this application. The land cover which is associated with parameter Srmax, is reclassified into four classes as deep rooted (forest), shallow rooted (grass/shrub), shallow rooted and irrigated (crop), and impervious to reduce the number of parameters to be calibrated. There are altogether 23 soil textural classes present in the catchment. 5 RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS This paper presents a method to estimate the parameter values associated with soil characteristics (T0) in a distributed hydrological model (BTOPMC). The new approach is applied to the Mekong River basin and the results are compared with the normal application. The parameter sets resulting from the two different approaches (Table 2) are similar except for the T0 value. However the parameter set obtained in the new approach seems to be more physically based than the normal application (e.g., normally the T0 value for silt should be higher than that for clay). The model performance in both applications (Table 3) is acceptable both in calibration and validation stages (for Pakse). However the model performance with the new approach is slightly better than the normal application. The hydrographs (Figures 2 & 3) show a good agreement between the observed and calculated discharges in both applications except for few extreme events. The model performance (validation) at the Mukdahan station from 1978 to 1985 is better than the period 1972 to 1977 (Table 3). However the parameter set calibrated using the Pakse observed discharge data is valid for the Mukdahan station. This implies that the calibrated parameter set is strongly physically based. In the normal application, the T0 value of each grid is assumed as the T0 value of the dominating soil type present in the grid, which seems to be unrealistic especially when nearly equal percentages of soil types (sand, silt, and clay) are present. In fact the reclassifying or grouping soil types is unrealistic and an unnecessary source of uncertainty. In the new approach, we only have to ever estimate three parameters to represent all possible soil textural combinations regardless of how many soil types are present in the basin to be modeled. This also makes it particularly appealing for the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS) Prediction in Ungauged Basins (PUB) project since all we need to know to estimate T0 is the percentages of sand, silt, and clay in each grid which is readily available - even though T0 may change slightly from region to region this can be determined by future applications in numerous different basins. It is clear that the new approach used to calculate the T0 value in the BTOPMC enhances the model performance and eliminates the uncertainty associated with soil classification, as well as improving the physical soundness of the model. However, further investigations are necessary to determine whether using non-linear functions to calculate T0 is more suitable than the linear function (Eq. 1) used in this study. 6 0.0 100000 10.0 20.0 30.0 60000 Preci Qobs Qs im 40.0 40000 Precipitation (mm) Discharge (m3/s) 80000 50.0 20000 60.0 01/01/1984 01/01/1983 01/01/1982 01/01/1981 01/01/1980 01/01/1979 01/01/1978 01/01/1977 01/01/1976 01/01/1975 01/01/1974 01/01/1973 70.0 01/01/1972 0 Date Calibration Figure 2. Observed and simulated hydrographs of the modified application (at Pakse) 0.0 100000 10.0 20.0 30.0 60000 Preci Qobs Qs im 40.0 40000 50.0 20000 60.0 Calibration Date Figure 3. Observed and simulated hydrographs of the normal application (at Pakse) 01/01/1984 01/01/1983 01/01/1982 01/01/1981 01/01/1980 01/01/1979 01/01/1978 01/01/1977 01/01/1976 01/01/1975 01/01/1974 01/01/1973 70.0 01/01/1972 0 Precipitation (mm) Discharge (m3/s) 80000 7 Table 2. Calibrated parameter sets Impervious Application Srmax Modified application 0.0001 Normal application 0.0001 Forest Srmax 0.750 0.750 Grass Srmax 0.738 0.738 Table 3. The performance of the BTOPMC model Calibration Pakse Nash Vol% Qo/P% Modified application 82.70 101.60 38.40 Normal application 82.30 103.70 38.40 Mukdahan Modified application 69.50 115.00 39.40 Normal application 68.10 117.40 39.40 Crop Srmax 0.745 0.745 Clay T0 50.0 45.0 Sand T0 300.0 200.0 Silt T0 150.0 25.0 Qs/P% 39.00 39.80 Ea/P% 62.80 62.80 Nash 81.70 81.40 Vol% 102.00 102.55 45.30 46.20 53.60 53.60 73.40 72.80 110.20 111.20 n0 0.2 0.2 m 0.030 0.030 S0 0.001 0.001 Validation Qo/P% Qs/P% 39.90 40.55 39.90 40.75 43.00 43.00 47.40 47.90 Ea/P% 61.35 61.35 51.60 51.60 Note: Nash is the Nash-Sutcliffe coefficient, Qo and Qs are the observed and simulated discharges respectively (m3/s), Vol%=Qs/Qo%, P is the precipitation (mm) and Ea is the actual evapotranspiration (mm) 8 REFERENCES [1] Ao T. Q., Yoshitani J., Takeuchi K., Fukami K., Mutsuura T. and Ishidaira H., “Effects of sub-basin scale on runoff simulation in distributed hydrological model: BTOPMC”, Weather Radar Information and Distributed Hydrological Modeling (Proc. of symposium HS03 held during IUGG2003), Sapporo, IAHS Publ. No. 282, (2003). [2] Beven, K. J. and Kirkby, M. J., “A physically based, variable contributing area model of hydrology”, Hydrol. Sci. Bull., Vol 24, No. 1, (1979), pp 43-69. [3] Beven, K. J. and Binley, A. M., “The future of distributed models: model calibration and predictive uncertainty”, Hydrol. Processes, Vol. 6, (1992), pp 279-298. [4] Duan, Q., Sorooshian, S. and Gupta, V. K., “Effective and efficient global optimization for conceptual rainfall-runoff models”, Water Resour. Res., Vol 28, No. 4, (1992), pp 1015-1031. [5] Quinn, P. F., Beven, K. J. and Lamb R., “The ln(a/tanâ) index: how to calculate it and how to use it in the TOPMODEL framework”, Hydrol. Processes, Vol. 9, (1995), pp 161-182. [6] Takeuchi. K., Ao, T. Q. and Ishidaira, H., “Introduction of block-wise use of TOPMODEL and Muskingum-Cunge method for the hydro-environmental simulation of a large ungauged basin”, Hydrol. Sci. J., Vol. 44, No 4, (1999), pp 633-646. [7] UNESCO, “World water balance and water resources of earth”, English translation, USSR committee for the international hydrological decade, (1978). [8] Verdin, K. L. and Verdin, J. P., “A topographical system for delineation and codification of the Earth’s river basins”, J. Hydrol., Vol. 218, (1999), pp 1-12. [9] Zhou, M. C., Takeuchi, K., and Ishidaira, H., “Special and temporal distribution patterns of potential evaporation and evapotranspiration at Mekong and Yellow river basins”, Proc. Of 2003 annual conference, Fukoka, Japan society of hydrology and water resources, (2003), pp 192-193.