Reading Notes

advertisement

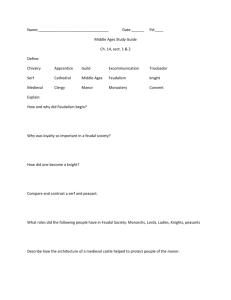

Reading_Notes_Chapter_11 The Fourteenth Century This is a rather short chapter to cover as much as it does, so it is difficult to abbreviate it much, but I shall try as I guide you step by step through the chapter. p. 257, para 1: Here again we have a brief summary of the ups and downs of the century; it’s not bad as a very quick summary. p. 257-258: This opening analogy between what is medieval and what were the “Sixties” might work for you; it might not. But part of this chapter is going to press the idea that there is more continuity between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance than is often taught, a point, by the way, that I totally agree with. pp. 258-261: Here are described some of the big religious controversies of the period, and they are big, but they are also rooted in past developments that you already know about. p. 258: Babylonian Captivity 1305-1377: Papacy moves from Rome to Avignon in France, under the thumb of the French king. p. 258-259: Great Schism 1378-1415: multiple popes, two to three at given times. p. 259: Council of Constance (1414-1418): settled the Schism p. 260: Lollard heresy in England; the followers of John Wyclif (d. 1384), anti-papal stance with many proto-Protestant ideas. pp. 260-261: Hussite Rebellion – followers of John Hus in Prague (executed in 1415), also inspired by Wyclif and also inspiration of Martin Luther in the next century. pp. 261-264: Major Political Developments: The thing you look for at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance are the following: Rise of Cities and City States; Rise of Absolute Monarchies; Rise of Middle Classes. pp. 261: Most of the same strong states are evident at this late stage. Germany and Italy do not become kingdoms or nations for quite a while. The kingdoms of Aragon and Castile merged to create, basically Spain, in the 15th century. The dream of a world government that Dante wrote about still bothers leaders and intellectuals. p. 262: Italy. While Italy is not consolidated as a nation till the 19th century, there are some powerful kingdoms in Northern Italy (Lombardy), middle (Papal States) and the south (Sicily). Italy’s northern region developed some of the most important city states: Florence, Pisa, Siena, Milan, and Venice. In the south Naples emerged as a powerful kingdom as well and ruled by the French in the 14th century. p. 262-264: 100 Year’s War. This is the war between England and France that lasted longer than a hundred years. The dates are usually 1337 to 1453. Actually, though the war was less like a concentrated war between than a series of wars. England seemed to win the most territory in the early years and France more in the later years. The effects of the wars, like that of the Crusades, was to solidify national identify, increase hatred, kill off a lot of people, and devastate some land. In some ways the causes of the war go back to William the Conqueror in 1066 and the situation of a French duke being at the same time an English king. Later the English king Henry II in his marriage to Eleanor seemed to rule a great deal of western France. So these English claims of French land can be seen to date back to French claims of English land. pp. 262-263: This was is sometimes considered the last to be fought according to the rules of chivalry, and there is some historical support for this. Notice the quote from a contemporary of the time Jean Froissart who described Edward III’s creation of the knightly Order of the Garter. pp. 263-264: Two important women of the Hundred Years War are Joan of Arc and Christine de Pizan. Joan’s story is extremely popular and powerful; she is still revered as a saint, and many people make pilgrimages to all the sites associated with her remarkable career. There is a movie about her life for every generation. She led the French army to victory, ensured the crowning of a rather weak prince, and was captured, tried, and executed in 1431. Christine is sometimes referred to as the first successful professional woman writer. She was widowed early and had to make a living for her and her children with little family support, and so her biographers claim she made a living with her mind and her pen. She wrote on a number of subjects, but the Book of the City of Ladies is noteworthy as a very progressive feminist argument for the recognition of the importance of women in culture. pp. 264-268: Section on Medieval Philosophy: This is a section you could easily skip, I think, unless you have an interest in philosophy. The section does not go into enough depth to do most of you any good. It starts out pointing the age-old joke about medieval Scholasticism that they spent all their time arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. There is some truth to this statement, yes, but it is also applicable at any time in the history of philosophy. On page 266 the reputation of Thomas Aquinas is discussed and because his theology as become the dominant theology of the Catholic Church and many of those associated with its history, it is relevant. Bonaventure is mentioned as the dominant intellect in the same time period (both died in the year 1324) in the Franciscan tradition. p. 267: Another philosophical tradition that developed in the 14th century was Nominalism. This tradition is more amenable to science, as we understand it, and a little less patient with reasoning about God. William of Ockham, a Franciscan, is the dominant figure in this school. pp. 268-271: Black Death or Plague. This is a significant cultural event because the result of the plagues that began in the year 1348 was to destroy about a third of Europe’s population. This has serious effects on labor, religion, art, and politics. p. 268: Religious response. There were lots of communities that assumed the plague was the result of their sin and they redoubled their devotion. The flagellants are mentioned on this page, people who go about whipping themselves for their sins. p. 269: Scapegoating: Another response was to blame a group for sinful ways. The Jews were often the target of this abuse. p. 270: There were some advances in medicine and hospital development as a result of the plague, not as much as one would like, but still some learned about treatments and took a more scientific approach to the body and disease. Greek and Arabic texts were looked at more often during this period. p. 270: Political Unrest. Three uprisings are cited in your text that resulted to some degree from the plague: Jacquerie in Paris in 1356; the Ciompi revolt in Florence in 1378, and the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381. In all three of these, disenfranchised laborers rose up, with violence, against the upper classes who were taking advantage of their labor. How did this result from the plague? Well, in crass economic terms: the plague reduced the supply of their labor and while demand remained constant their value should have gone up but did not. The peasants were aware of this and demanded a change. pp. 271-278: The Rise of the Renaissance. This is a section you could skim, really, but again if you are interesting it is not long and it goes to the heart of the medievalism question of this course. The question is what and why is their continuity with the Middle Ages today? There must be something we share and there must be something that we don’t that we find interesting. p. 271: Citing the two paintings of the Madonna, the authors plainly state that there is a change in sensibility that happened sometime around the 14th or 15th century. Botticelli’s Renaissance Madonna is a world of difference from the 13th century, equally beautiful one by Cimabue, equally beautiful, I say, but very different aesthetics. p. 272: Having admitting that something happened to create a new sensibility, the authors are quick to point out that historians from the Renaissance forward have been too quick to label every bad medieval and everything good Renaissance. They cite the Jacob Burckhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) as one of the great promulgators of this myth. And they are right; Burckhardt’s book did much to create this somewhat false dichotomy that exists. p. 272-277: The authors go on to counter the Burckhardtian thesis on the use of classical texts by citing numbers classical or pagan authors used in the Middle Ages and nonmodern uses of pagan texts in the Renaissance period. Plato, Aristotle, Homer, Ovid, Virgil, and Cicero are cited. pp. 275-277: Perhaps the best case they make is focused on the figure of Petrarch. He is a fourteenth-century Italian who is as much celebrated as a late medieval as well as an early Renaissance figure. He truly is a person of both worlds. The authors provide a brief analysis of his famous letter about a climb up Mount Ventoux, in southern France. He expresses a modern motivation of wanting to see from the mountain and he uses Livy, a classical writer, to support this motivation, but after his climb he realizes that his climb is an allegory of the life of the spirit and he goes to Augustine and returns to a focus on the invisible life, a medieval turn. Petrarch, therefore, stands like much of the Middle Ages to us, a place where we can differ from a lot, but a place where we can find continuities and maybe origins of much of the culture that surrounds us.