One Voice More on Berlin`s Doctrine of Liberty

advertisement

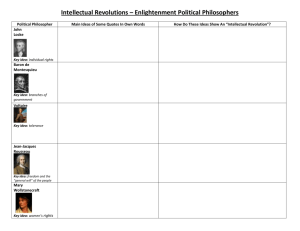

308 ONE MORE VOICE ON BERLIN’S DOCTRINE OF LIBERTY I Isaiah Berlin's famous essay on political freedom, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” 1 was described by Marshall Cohen as “academic, inflated and obscure.”2 It is perhaps an indication of the value of the essay that it should produce such a violent reaction. However, this characterisation of the essay has relevance to the problem of political liberty itself, for there is no doubt that the concept is of its nature obscure. Nevertheless, though philosophically so vague, the burning issue of liberty cannot be treated as merely academic in the contemporary world. Let this serve as justification for my adding one more voice to a long and complex discussion. II Participants in the debate have recognised different threads of Berlin's essay as the most significant ones. Many have concentrated on his conception of negative freedom, some criticising its narrowness and tracing its links with classical liberalism.3 It seems to me, however, that the main value and originality of Berlin's approach lies not so much in his discussion of negative liberty but in his perceptive critique of the positive concept. The proportions of the essay devoted to the two aspects in a way confirm this impression. Berlin devotes 9 pages to understanding of the negative concept, whereas his critique of the positive concept occupies 24 pages. Some commentators have discussed both threads of Berlin’s essay. Nevertheless, what 309 most of them have concentrated upon has been the distinction between the two concepts, not the critique of the positive one.4 Several authors claim to have solved the problem by arguing away the distinction.5 A significant exception is Charles Taylor, who questioned Berlin’s whole approach to the relationship between the negative and positive concepts.6 But in my opinion the only author to have taken up and elaborated upon the most original part of Berlin's doctrine, namely the critique of the positive concept, is C. B. Macpherson. This is the only discussion that does not evade in one way or another Berlin's central thesis that positive doctrines of liberty are particularly susceptible to distortion.7 C. B. Macpherson attempts to refute Berlin's main argument in the following way. He quotes Berlin's statement of the four central assumptions of the positive view of liberty: “first, that all men have one true purpose, and one only, that of rational self-direction; second, that the ends of all rational beings must of necessity fit into a single universal, harmonious pattern, which some men may be able to discern more clearly than others; third, that all conflict, and consequently all tragedy, is due solely to the clash of reason with the irrational or the insufficiently rational – the immature and undeveloped elements in life whether individual or communal, and that such clashes are, in principle, avoidable, and for wholly rational beings impossible; finally, that when all men have been made rational, they will obey the rational laws of their own natures, which are one and the same in them all, and so to be at once wholly lawabiding and wholly free.”8 Macpherson maintains that only the first assumption is inherent in all doctrines of positive freedom. In other words, he questions Berlin's thesis of the necessary logical bond between the notion of “freedom to” and rationalist monism. According to Macpherson the first assumption is even inconsistent with the last three. For what flows from the acceptance of the “positive” idea of freedom is not “a preordained harmonious pattern”9 but a “proliferation of many ways and 310 styles of life.”10 A hint of the same view, that there is no logical connection between rational self-direction and rationalist metaphysics, has been expressed by John Gray: “I suggest that some useful variant of the idea of a real or rational will may survive the demise of the rationalist metaphysics and philosophical psychology in which it has traditionally been embedded.” 11 Robert Kocis's conception of rational self-direction is also similar to that of Macpherson: “ ‘self-actualisation’ is not a single goal, but a series of (probably conflicting) goals,” 12 “there are many forms of selfrealisation.”13 Isaiah Berlin maintains his view and simultaneously rejects Macpherson's objection. According to him, the first assumption implies that to every problem there is in principle only one objective solution. If there is no answer, in principle, to a question, or if there are two answers, it cannot be a real question. Thus, “my realisation of myself as a rational being must rest on the perception of what the problem is. To this question there is in principle only one true answer. What is true of me is also true of you in similar circumstances, because we are both human beings.”14 At this point the door is open to rationalist metaphysics. Thus the idea of rational self-realisation logically entails the conviction expressed in the last three assumptions, if it is taken strictly. III This question has yet another dimension. The problem of human liberty is an object of concern in many intellectual fields other than general political theory – philosophy, social psychology or literature, for example. It is the role of the last to reflect the mood of contemporary culture. My impression is that one does not often nowadays come across the parallel of freedom as an 311 experience of space in an upward flight. Naive as this remark may be, the ancient myth of Icarus can be taken as the incarnation of the idea of “freedom from.” This very notion, though limited to the social context, seems to form the basis of the classical liberal image of freedom. The vision one encounters today has much more affinity with Kierkegaard's choice of the existential stage or Heidegger's postulate of authentic existence than with Icarus' flight. It is no longer the space devoid of obstacles but the horizon of choice that stands for human liberty. Let me back this digression up with some quotations which, though chosen at random, speak for themselves. It is how two modern writers, Thomas Merton and Alberto Moravia, see human liberty. “I cannot make the universe obey me. I cannot make other people conform to my whims and fancies. I cannot make even my body obey me. When I give it pleasure, it deceives my expectation and makes me suffer pain. When I give myself what I conceive to be freedom, I deceive myself and find that I am the prisoner of my own blindness and selfishness and insufficiency … we too easily assume that we are our real selves, and that our choices are really the ones we want to make, when, in fact, our acts of free choice are (though morally imputable, no doubt) largely dictated by psychological compulsions, flowing from our inordinate ideas of our own importance. Our choices are too often dictated by our false selves.”15 “a man has a beautiful life when he is free, when he lives according to his own principles, directing himself by his own internal inspiration, and not humbly sticking to universally valid norms. To live beautifully means to choose one's own way and follow it despite the price one has to pay. To me that man has lived his life beautifully who has had an opportunity to reveal the whole fullness of his personality, not the one who has lived “respectably.” A man does not live to be “respectable,” but to express himself as a personality. To me an opportunity of human fulfilment is a synonym for freedom.”16 It was [the] contemporary reality that generated existentialism and induced this very notion of 312 human freedom. IV Let us now return to the social context. Reading Fromm's Fear of Freedom, one cannot help noticing certain parallels: “positive freedom consists in the spontaneous activity of the total, integrated personality.”17 While Merton and Moravia drew their visions of liberty from the standpoint of the isolated individual, Fromm's conception undoubtedly involves a social context. And this is where the political theorist should apply all his imagination. The following excerpt strikes a reader of Fromm as especially significant. “Positive freedom also implies the principle that there is no higher power than this unique individual self, that man is the centre and purpose of his life: that the growth and realisation of man's individuality is an end that can never be subordinated to purposes which are supposed to have greater dignity.”18 It is worth mentioning that a similar idea was put forward by one of Berlin's critics, namely by Charles Taylor. “each person has his/her own original form of realisation. Some others, who know us intimately, and who surpass us in wisdom, are undoubtedly in a position to advise us, but no official body can possess a doctrine or a technique whereby they could know how to put us on the rails, because such a doctrine or technique cannot in principle exist if human beings really differ in their self-realisation.”19 Does this mean that both authors somehow want to protect their doctrines against potential distortions? Why did they take such precautions? Were they aware that their conceptions were vulnerable to perversion? Let us now examine the origin of such an apprehension. 313 An explanation of this problem is provided by “Two Concepts of Liberty.” The adherents of the positive view of freedom, however, would challenge Isaiah Berlin's critique and probably his line of defence. It seems valid to follow their argument and to examine the theoretical consequences that may be drawn from their vision of liberty. Let us concentrate upon one concrete doctrine, namely that of C. B. Macpherson. What follows from his simultaneous acceptance of the first assumption (that is, that all men have one true purpose, and one only, that of rational self-direction) and rejection of the rationalist monism which he claims is inherent in the last three assumptions? If there is no universal pattern and liberty is understood in the positive way, a countless number of collisions are bound to emerge. This is because any social doctrine aiming at regulating relationships among men must provide some universal principle. Classical liberalism structured society by granting every individual an independent sphere. There is no way in which liberty identified with self-realisation and abstracted from any universal pattern of development could perform the same role. What is it then that can make the positive doctrine of freedom a social one, not merely an individualist, possibly existentialist, conception of personal self-fulfilment? It is my thesis that every defence of positive liberty presupposes some tacit, universal value that fulfils the task of structuring society. This value is seen as indispensable and fundamental. At the same time, given the great persuasive appeal of the term “liberty,” it is hard for a theorist to abandon the concept. Thus he expands or even changes its meaning in order to protect the preferred value. Is this the case in Macpherson's discussion? Let us come back once again to his paper. The following excerpt seems to support my contention. “if the chief impediments to men's developmental powers were removed, if, that is to say, they were allowed equal freedom, there would emerge not a pattern but a proliferation of many ways and styles of life which could not be prescribed and which would not necessarily conflict.”20 314 However, the removal of the “chief impediments,” which is essential to achieving “equal freedom,” implies the emergence of an authority which would perform the task. By providing equal conditions for self-realisation, the authority must simultaneously define them. Thus it will not be merely the scope of an individual's independent sphere that will be decided upon by some external authority, but also the very content of his freedom. This model is bound to produce a limited range of patterns (if not one), rather than a proliferation of many ways and styles of life. In conclusion, it seems to me that Berlin's main thesis that positive conceptions or liberty are particularly susceptible to distortions remains valid. For if a doctrine of “freedom to” is to fulfil a social function, it must provide some principle, whether explicit or implicit, by which to structure society. In both cases the term “liberty” loses its original connotation as a sphere of independence and will mean whatever a theorist wishes. 1 Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” in: Liberty, pp. 166–217. 2 Marshall Cohen, “Berlin and the Liberal Tradition,” The Philosophical Quaterly 10 (1980): 216. 3 See Arnold S. Kaufman, “Professor Berlin on Negative Freedom,” Mind 7l (1962): 241–3; Cohen, “Berlin and the Liberal Tradition,” pp. 216–27, Hillel Steiner, “Individual Liberty,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 75 (1974–5): 33–6; John Gray, “On Negative and Positive Liberty,” in: Liberalisms, pp. 62–4. For discussion on the disadvantages of the rigid negative approach, see also Alan Ryan, “Freedom,” Philosophy 40 (1965): 108–11. 4 See Gray, “On Negative and Positive Liberty,” pp. 48–51; John Gray, “Introduction,” in: eds. Zbigniew Pelczynski and John Gray, Conceptions oj Liberty in Political Philosophy (London: Athlone Press, 1984), pp. 4–6; Henry J. McCloskey, “A Critique of the Ideals of Liberty,” Mind 315 74 (1965): 483–6; Leslie J. Macfarlane, “On Two Concepts of Liberty,” Political Studies 14 (1966): 77–81; David Nicholls, “Positive Liberty,” American Political Science Review, 56 (1962): 114–15, ft 8. For an objection on the ground of the incompletness of the two concepts of liberty see also Stanley I. Benn, “Freedom and Persuasion,” The Australasian Journal of Philosophy 45 (1967): 260–2. See Gerald MacCallum, Jr, “Negative and Positive Freedom,” The Philosophical Review 76 5 (1967): 312–34; Joel Feinberg, Social Philosophy (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1973), pp. 9–14; William A. Parent, “Some Recent Work on the Concept of Liberty,” American Philosophical Quarterly 11 (July 1974): 149–67 (see especially pp. 152 and 166). 6 Taylor, “What's Wrong with Negative Liberty,” pp. 175–93. Macpherson, Democratic Theory, pp. 95–119. Though Cohen does actually engage in a 7 discussion on Berlin's critique of the conceptions of positive freedom, he conducts it from a position of fundamental disagreement: see: Cohen, “Berlin and the Liberal Tradition,” pp. 218, 221–7. 8 Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” in: Liberty, p. 200. 9 Macpherson, Democratic Theory, p. 112 10 ibid., p. 111. 11 Gray, “On Negative and Positive Liberty,” p. 59. 12 Kocis, “Toward a Coherent Theory of Human Moral Development,” p. 375. 13 ibid, p. 386. 14 Isaiah Berlin in conversation with the author, July 1986. 15 Thomas Merton, No Man Is an Island (London: Hollis & Carter, 1955), pp. 20–1. 316 16 This is my translation from an interview with Alberto Moravia, published in a Polish periodical: “Podroz po wyboistej drodze z Alberto Moravia,” Forum 48 (1977): 18. 17 18 Fromm, Fear of Freedom, p. 222. ibid., p. 228. 19 Taylor, “What's Wrong with Negative Liberty,” p. 180. 20 Macpherson, Democratic Theory, pp. 111–12.