Home hygiene, pets and other domestic animals

advertisement

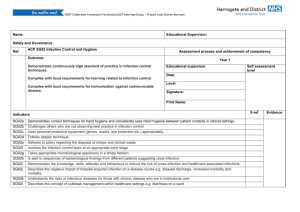

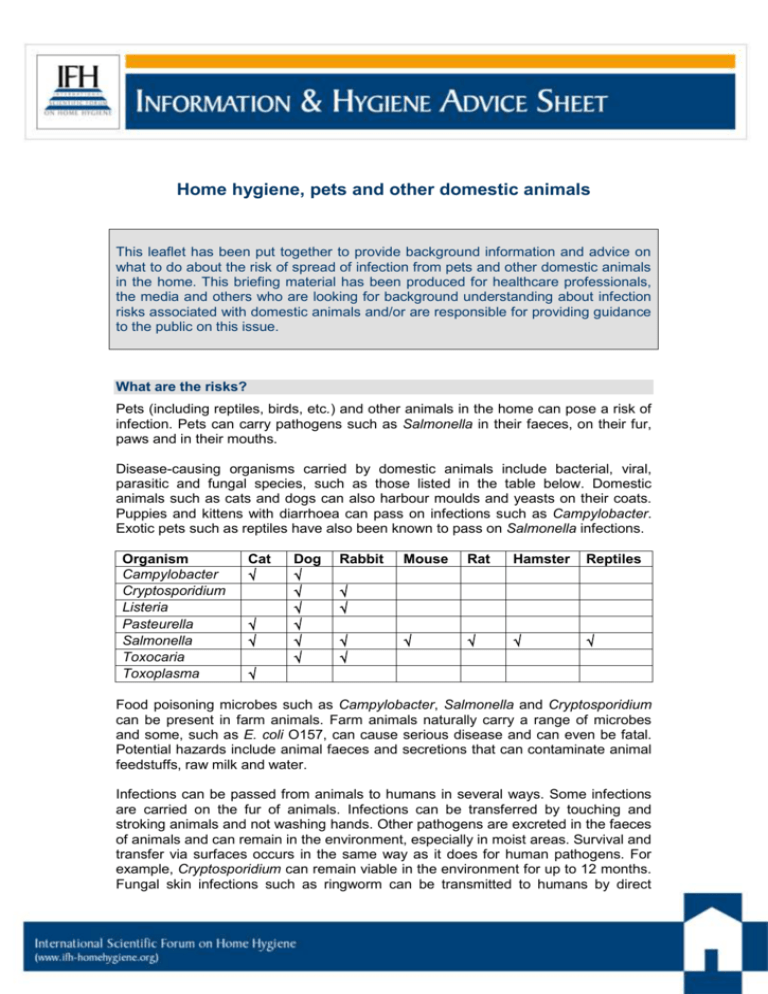

Home hygiene, pets and other domestic animals This leaflet has been put together to provide background information and advice on what to do about the risk of spread of infection from pets and other domestic animals in the home. This briefing material has been produced for healthcare professionals, the media and others who are looking for background understanding about infection risks associated with domestic animals and/or are responsible for providing guidance to the public on this issue. What are the risks? Pets (including reptiles, birds, etc.) and other animals in the home can pose a risk of infection. Pets can carry pathogens such as Salmonella in their faeces, on their fur, paws and in their mouths. Disease-causing organisms carried by domestic animals include bacterial, viral, parasitic and fungal species, such as those listed in the table below. Domestic animals such as cats and dogs can also harbour moulds and yeasts on their coats. Puppies and kittens with diarrhoea can pass on infections such as Campylobacter. Exotic pets such as reptiles have also been known to pass on Salmonella infections. Organism Campylobacter Cryptosporidium Listeria Pasteurella Salmonella Toxocaria Toxoplasma Cat Dog Rabbit Mouse Rat Hamster Reptiles Food poisoning microbes such as Campylobacter, Salmonella and Cryptosporidium can be present in farm animals. Farm animals naturally carry a range of microbes and some, such as E. coli O157, can cause serious disease and can even be fatal. Potential hazards include animal faeces and secretions that can contaminate animal feedstuffs, raw milk and water. Infections can be passed from animals to humans in several ways. Some infections are carried on the fur of animals. Infections can be transferred by touching and stroking animals and not washing hands. Other pathogens are excreted in the faeces of animals and can remain in the environment, especially in moist areas. Survival and transfer via surfaces occurs in the same way as it does for human pathogens. For example, Cryptosporidium can remain viable in the environment for up to 12 months. Fungal skin infections such as ringworm can be transmitted to humans by direct contact with animals. Water-borne transmission from pets to humans has also been documented. Infections can be passed on from animals in the kitchen. It is thus important to keep separate equipment for pets and to clean surfaces where pets have touched. How big is the risk? More than 50% of homes in the English-speaking world have cats and dogs, with an estimated 60 million cats and dogs in the USA. In 2007, a telephone survey of UK households revealed that cats and dogs were owned by 26% and 31% of households, respectively. It is estimated that there are around 10.3m cats and 10.5m dogs in the UK Domestic cats and dogs can carry organisms such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA and PVL-producing strains) and Clostridium difficile. Exotic pets such as reptiles and turtles can also be a source of infection e.g. Salmonella. Some examples of the occurrence of disease-causing organisms in domestic animals are as follows: In the USA, up to 39% of dogs may carry Campylobacter, and 10–27% may carry Salmonella A London study isolated 19 species of Campylobacter spp. from 100 specimens of faeces obtained from a cattery, including Campylobacter upsaliensis and Campylobacter jejuni A Canadian study showed that C. difficile was the most frequently isolated pathogen from dogs. C. difficile was isolated from 58 (58%) of 102 faecal specimens, of which 41 isolates were disease-causing strains. Feeding raw meat to dogs may have an impact. A Canadian study identified Campylobacter jejuni from 2.6% of raw meat-fed dogs and Salmonella enterica from 14% of raw meat-fed dog faeces. Salmonella enterica was recovered more frequently in the vacuum cleaner waste samples from households with raw meat fed dogs than from those where raw meat was not fed to dogs (10.5% versus 4.5%). There are numerous reports of MRSA carriage in household pets which is closely linked to MRSA in humans. In some cases it is concluded that that the original source of MRSA in pets or other animals may often be colonised or infected humans. It must be borne in mind that many pets that carry infectious agents do not appear ill. Although there is little data indicating the extent of the infection risk from animals in the home (i.e. how often infections are acquired from animals in the home) a number of studies show situations where pets were identified as a risk factor for infection: A study of 50 US homes in which children under 4 years were known to be infected with Salmonella spp. showed that, in 34% of homes, there was also illness in another family member. The data indicated that environmental sources, infected family members and also pets, are more significant risk factors for development of salmonellosis in these children than contaminated foods. In 3 studies, discharged MRSA-infected hospital patients and health care workers were successfully treated at home to eradicate the organism, but subsequently became re-colonised. In each of these cases the evidence suggested that the source of re-colonisation was a domestic dog. Page 2/6 The UK HPA report data indicating that reptile pets may pose a Salmonella risk to infants in the home. Salmonella arizona is commonly found in the gut of reptiles, with snakes being the largest reservoir of infection. HPA reported a significant increase in reported infections with S. arizona that may be a reflection of the increased popularity of reptiles as pets. In England and Wales in 2007, 55 human cases of S. arizona were reported out of 11,943 non-typhoidal salmonellas (0.46%) compared with 30 cases out of 23,134 non-typhoidal salmonellas (0.13%) reported in 1998. People in close contact with farm animals are at risk of animal-to-human transmission of Salmonella Typhimurium DT104A variant. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was isolated from a pig, a calf, and a child on a farm in The Netherlands. The isolates were indistinguishable by typing methods, which suggested non-foodborne animal-to-animal and animal-to-human transmission. From a review of data from 1993 to 1995, the US CDC estimated that 3-5% of 20,000 laboratory-confirmed human cases of salmonellosis in Canada were associated with exposure to exotic pets In 2008 transmission of PVL-positive MRSA between a symptomatic woman and both her asymptomatic family and their healthy pet cat was reported. This illustrates how MRSA transmission can occurs between humans and cats and that pets should be considered as possible household reservoirs of MRSA that can cause infection or reinfection in humans. In 2013 a study of 79 households in Germany with children suffering from gastroenteritis due to an exotic Salmonella serovar was reported. Almost half (34/79) had at least one reptile pet in the home. Nineteen households and 36 reptiles were further investigated. In 15 of 19 households, an identical strain to the human case was confirmed in at least one reptile. Results showed that reptiles, especially bearded dragons, shed various Salmonella serovars including those isolated from infected children in the respective households. The report is available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20634 A 2011 review concluded that, besides humans, perhaps the most important community reservoirs of staphylococci are pets and livestock (1). He cites evidence showing that MRSA has been isolated from pigs, horses, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, chinchillas, and parrots. Targeted sampling suggests that up to 8% of dogs, 12% of horses, 15% of lactating cows, 14.3% of broiler farms, and 68% of fattening pig farms were potentially positive for MRSA. In many cases, MRSA clones from animals were shared by their owners and/or handlers, suggesting the possibility for MRSA transmission between animals and humans Human pathogens can also be associated with wild and migratory birds. Indirect transmission to humans has been reported for some of these such as E. coli and Salmonella spp., but little or no evidence of direct infection transmission from wild birds to humans. Data assessing the infection risks associated with pets and domestic animals is further reviewed in a 2012 IFH report (2). Escherichia coli O157:H7 Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 strains are carried primarily by healthy cattle and other ruminants, but most bovine strains are not transmitted to people, or cause disease. Virulent strains of EHEC O157:H7 are rarely harbored by Page 3/6 pigs or chickens, but are found in turkeys. The main reservoir for E. coli O157 is the intestine of healthy cattle and other farm animals. The bacteria can survive in faeces and soil. Carcasses can become contaminated through contact with intestinal contents at slaughter. Transmission to people occurs mostly through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Although less frequent, it can also through contact with manure, animals, or animal keepers, particularly through farm visits (3). Domestic animals and high risk groups in the home “At risk” groups are at particular risk of infection from domestic animals in the home who may be infected or carrying pathogenic spp. Demographic changes and changes in health service structure mean that the number of people in the home needing special care, because they are at increased risk of infection, is increasing. The largest of these “at risk” groups are the elderly who have reduced immunity to infection which is often exacerbated by other illnesses such as diabetes, etc. It also includes the very young, patients discharged from hospital, taking immunosuppressive drugs or using invasive systems, etc. It also includes the estimated 40 million people in the global community who are infected with HIV/AIDS. In particular: Pregnant women should not handle litter trays as pathogens excreted in animal faeces, e.g. Toxoplasma gondii, can affect the developing foetus. Listeria is also a particular risk for pregnant women. Pregnant women should avoid eating cheeses made from unpasterised milk. If there is a baby in the house, ideally, reptiles should not be kept. Are we too clean for our own good? How, and to what extent, parents should protect infants and children from infectious illness has been the subject of much debate in recent years. In the last 30 years we have seen an epidemic of chronic inflammatory diseases in the industrialized world. For young children the major concern is asthma, hayfever, food and other allergies, but, in reality, the problem extends to a broader range of diseases including Type 2 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis. The concept of a link between reduced “infection” exposure and increasing levels of allergic diseases, as first proposed in the 1990s, was named the hygiene hypothesis. This fuelled the idea that we have become too clean for our own good, and still persists, despite the fact that the hypothesis has been substantially revised. A more rational explanation, the ‘Old Friends’ hypothesis, is now becoming more widely accepted and argues that the vital exposures are not colds, influenza, measles and other common childhood infections which have evolved relatively recently over the last 10,000 years, but the microbes already present over 2 million years ago in hunter-gatherer times when our immune system was developing. Although we cannot be sure precisely what microbes are involved, current thinking is that the Old Friends organisms include harmless commensal microbes found on human and animal bodies and in the gut, and organisms from the natural environment. It also includes some infections such as parasitic worm infections that can persist as relatively harmless carrier states. It seems probable that exposure to a diverse range of these organisms is important, particularly early in life. There is some evidence that cats or dogs in the home can protect against allergies in children because they can be a source of exposure to “Old Friends” (4). Page 4/6 This suggests that, on one hand it is important not to become hygiene-obsessed, but on the other to maintain good hygiene practices. Babies are inevitably exposed to some micro-organisms in their environment which, in addition to germs will also include some of the Old Friends which need to become established as their normal gut flora, on their skin etc. Gradual exposure to small numbers of a wide range of microbes is also important for priming the immune system. The hygiene practices outlined below are important because they focuses on protecting infants against exposure to “infectious doses” of harmful organisms which our immune systems are not equipped to deal with. The latest findings on this issue can be found in a 2012 IFH review (5). Hygiene measures associated with pets and other domestic animals The principles of preventing the spread of pathogens from animals are the same as those for humans. Good handwashing practice is the single most important infection control measure. Hands should be thoroughly washed with soap and running water after handling domestic animals. Many pets that carry infectious agents do not appear ill and preventative measures such as washing hands after contact with pets is important. Pets and illness Ensure all animals are regularly groomed and checked for signs of infection. If a pet becomes ill, seek advice from a vet. Ensure all animals receive up-to-date immunisations and other important treatments such as worming and flea treatments. Pets and food Keep pet food separate from human food. Always wash hands after touching animals or their food, toys, litter trays, etc., especially before preparing food for human consumption. Ensure pet feeding areas are clean and animals have their own dishes and utensils. Dishes, utensils and tin openers used for pet food, should be cleaned and stored separately. Keep pets off kitchen surfaces or areas where food is prepared. Pets and cleaning Clean all cages and bedding regularly. Ensure litter trays are cleaned regularly (at least daily). Use gloves and paper towels to clean up animal faeces. Animal faeces can be flushed down the toilet. However, faeces in plastic bags and soiled cat litter should go into the waste bin. Hygienically clean floor surfaces used by pets and pet feeding areas regularly by cleaning followed by disinfection, or using a disinfectant/cleaner. Keep sandpits covered to avoid soiling by animals. Pregnant women should avoid cleaning cat litter trays . Farm animals On farm visits, ensure that the farm has washing facilities with running water, soap and disposable towels. Wash hands thoroughly after touching animals and before eating food. Page 5/6 Further reading 1. Kassem IA, Wooster, OH. Chinks in the armor: The role of the nonclinical environment in the transmission of Staphylococcus bacteria. Am J Infect Control 2011;39:539-41. 2. Bloomfield SF. Exner M, Signorelli C, Nath KJ, Scott EA. 2012. The chain of infection transmission in the home and everyday life settings, and the role of hygiene in reducing the risk of infection. http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/bestpractice-review/chain-infection-transmission-home-and-everyday-life-settings-androle-hygiene. 3. Ferens WA, Hovde CJ. Escherichia coli O157:H7: Animal Reservoir and Sources of Human Infection. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 2011:8(4). DOI: 10.1089=fpd.2010.0673 4. Bergroth E, Remes S, Pekkanen J, Kauppila T, et al. Respiratory Tract Illnesses During the First Year of Life: Effect of Dog and Cat Contacts. Pediatrics 2012:130:211-20. 5. Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Rook GA. The hygiene hypothesis and its implications for home hygiene, lifestyle and public health: summary. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/best-practicereview/hygiene-hypothesis-and-its-implications-home-hygiene-lifestyle-and-public IFH Home Hygiene Guidelines and Training resources Guidelines for prevention of infection and cross infection the domestic environment. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/best-practice-care-guideline/guidelinesprevention-infection-and-cross-infection-domestic Guidelines for prevention of infection and cross infection the domestic environment: focus on issues in developing countries. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/bestpractice-care-guideline/guidelines-prevention-infection-and-cross-infectiondomestic-0 Recommendations for suitable procedure for use in the domestic environment (2001). International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. http://www.ifhhomehygiene.org/best-practice-care-guideline/recommendations-suitableprocedure-use-domestic-environment-2001 Home hygiene - prevention of infection at home: a training resource for carers and their trainers. (2003) International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/best-practice-training/home-hygiene%E2%80%93-prevention-infection-home-training-resource-carers-and-their Home Hygiene in Developing Countries: Prevention of Infection in the Home and Peridomestic Setting. A training resource for teachers and community health professionals in developing countries. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: www.ifh-homehygiene.org/best-practice-training/homehygiene-developing-countries-prevention-infection-home-and-peri-domestic. (Also available in Russian, Urdu and Bengali) This fact/advice sheet was last updated in Jan 2014 Page 6/6