The History of 21 Acres` Land

advertisement

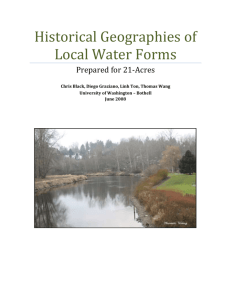

The History of 21 Acres' Land By Nan Hawthorne, a 21 Acres gardener Nature and human plans have governed the fate of the land on which 21 Acres is established. The effects of both destructive and creative forces of nature long preceded those of humans. Glaciation scoured the land, and then redeposited the first of the soils that would grow and grow into arable land, attracting the settlers who arrived in the late 19th century. Our acreage remained agricultural from thence to today. Landholders' efforts built and destroyed topsoil's while the Sammamish River floods augmented both. Now we are engaged in restoration and preservation of this land that has seen so much change. About 14,000 years ago, the land now occupied by 21 Acres was entirely covered by the Vashon Glacier. Its Pleistocene progenitor, the Puget Sound Lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, covered an area that extended from the Olympic Mountains to the Cascades as far as the south reaches of Puget Sound, obliterating whatever topography existed before. The ice sheet melted and left behind numerous glaciers. The melt water from the glacier from this part of the Vashon Glacier flowed south, then south and west carving what we now call the I-90 corridor, finally flowing to the northwest, a precursor of the present-day river. In the last stage of glaciation, the Vashon Glacier, receding north to its source in British Columbia, left behind the foundation for the soils here today. The uplands continued to show, the glacial till composed of gravel, sand and clay, which was dragged and formed by the receding ice. A combination of the melt water and succeeding floods over the land brought the lowlands its first topsoil. The river, the lowest point of the valley, developed marshes along most of its length, and the nitrogen-rich water and mud enhanced the topsoils further. Up until the late 1800s and clearing for farms in the area, the land was heavily forested with cedar, spruce and fir. What was called Squak Slough by the Simump people meandered through the valley with numerous twists and turns. In their language, "squak" means "marsh" and described the river and the land through which it wandered. It was approximately 30 miles from its source at Squak Lake (Lake Sammamish) to its destination in Lake Washington at what is now Kenmore. The slough flooded into the adjacent land and marshes on a regular basis. 1936 aerial view of Sammamish River Valley It is believed that the ancestors of the first humans to settle in the Pacific Northwest came here between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago at the end of the Ice Age, moving into lands that had been cleared of glaciers. The native people of the valley whereon 21 Acres lies, alternately called the Squak, Simump or Sammamish tribe were closely related to the Duwamish tribe on the other side of Lake Washington. Tlawahdees (my spelling), their largest village was at the mouth of the slough between Kenmore and Bothell, and another major settlement containing at least one longhouse was in the Issaquah area. When the Hudson's Bay Company explored the region in 1832, there were small settlements with a total population of 207 at various points along the river, perhaps explaining the translation of one of the tribe's names, "meandering people". Some members of the Simump tribe refused to accept the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, and, when government authorities sought to enforce the treaty by relocating members of many Puget Sound area tribes, they joined with Chief Sealth and the Duwamish in the Battle of Seattle and the ensuing if brief Puget Sound War. The result was the diaspora of the Simump people to reservations and non-reservation land by the Indian agent "Doc Maynard with the help of sawmill owner Henry Yesler. The 1862 smallpox epidemic decimated the local Native American populations. The descendants of former residents along the Squak Slough now live among the Suquamish, Snoqualmie, and the people of the Tulalip Reservation. Thanks to the fact that there was little difference in elevation of Squak Lake and Lake Washington, the Squak Slough was deeper and wider than it is now. It was easily navigated. Taking advantage of the National Homestead Act signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, Ira and Susan Woodin took possession of 160 acres to the northwest of 21 Acres, becoming the first permanent white settlers. The first person named in the county tax rolls as the owner of the land we are on was Emanuel Nielsen, one of a pair of brothers from Norway who settled in the land south of the Woodins. He owned 40 acres, which at that time was assessed at a value of $580. However, the land grant made by the Olympia office of the U. S. Bureau of Land management names Arthur L. Calkins as the recipient of the 1889 grant. Calkins and his family from Kansas apparently cancelled the land grant but appear to have stayed in the area. Land grant document By the cancelled land grant date of 1889, the Seattle-Lake Shore and Eastern Railway served the area. The famous steamboat the Mud Hen had abandoned plans to serve the valley after only one trip up the river in 1876 because the reeds and grasses in the river tangled the side wheels. The river was still useful for industries like logging that could move logs downriver. Still navigable by smaller boats, farming families would take the river and then cross Lake Washington to then walk the rest of the way to downtown Seattle to sell their produce and crafts and buy supplies. Early Homesteads - Is T. L. Calkins the original grant holder, Arthur L. Calkins? By the beginning of the 20th century, the river was doomed to change irrevocably. The forests that had shaded and filtered runoff into the river had been cleared for agriculture. The river flooded into this land so often that a coalition of farmers dredged sections and hardened the banks, resulting in the destruction of salmon habitats. The marshes that had produced the nitrogen rich soils the farmers enjoyed no longer had the cooling forests and fertile habitats that preserved these species. The land occupied now by 21 Acres, by this time divided into parcels 31 and 48 by the county tax assessor remained agricultural in spite of the growing town of Woodinville. Being so near the river, it was undoubtedly flooded regularly, a challenge for the farmers but also a source of new topsoil. The land passed from hand to hand, growing, dropping during the Great Depression and then growing again in assessed value. Nielsen sold the land by 1895, about 35 acres to G. C. Wooley and the remaining five to John Peterson. Wooley's 35 acres then passed to Stephen Collicott, whose family held fourteen acres of parcel 31 for another few decades, seeing it drop in value from $800 to $540 during the Depression. They built a house on the land, whose main floor was 900 square feet and whose attic was divided into two rooms. They put up a barn on the land in 1920. The house was torn down in 1956, just two years before it was deeded over to S. J. Brown in July, and a one-story house of twice the former house's size built. The Browns deeded the house and land over to Ida may Brown just four months later. Parcel 48's 20 acres, owned by the Peterson family, saw a similar drop in value from $1080 to $780 at the same time. A Kroll map from 1958 shows the owner as Vincent Kaehlin. In 1963, Charles Kaplan and his wife became the owners until the county acquired the land in the late 1990s. Throughout the decades, small improvements were made, including the building of structures as noted above, and the land was used variously for crops and dairy cattle. King County Tax Parcel Map In 1917, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under Hiram M. Chittendon completed the Lake Washington Ship Canal. The resulting 8.8 foot lowering of the surface of the lakes had a dramatic effect on the slough, which flowed too quickly and was to shallow for navigation. The slough was no longer useful for transporting logs or goods. Nevertheless, it continued to flood the neighboring farms and homes. A geologist from North Seattle recalled being taken by his father during the flooding of the Sammamish. Standing on the hill overlooking the valley, he said, "It was a lake." A King County/Army Corps of Engineers project, finished in 1964, straightened the slough, now called the Sammamish Slough or River, and essentially eliminated all flooding in the lower valley while reducing it in the area of 21 Acres. The river was now only thirteen miles long. The City of Woodinville, formerly part of unincorporated King County, was growing fast. Interstate 405 fed the existing state highways, SR 522 and SR 202, causing heavy traffic down the main street in town, NE 175th. The decision was made to create cutoff roads, one north of downtown and one south. The southern cutoff bisected the lands that had formerly been cleared farmland. NE 171st Street, now the address of 21 Acres, was born. The land north of this street was developed as apartments and condominiums. Formerly known as the Kaplan Farm, 21 Acres was purchased in the late 1990’s by King County Parks and Natural Resources. Friends of the Woodinville Farmers Market purchased the land from the County for $352,000 in January 2005. 21 Acres is part of King County’s Farmland Preservation Project. The impact on the river and land now results from feverish development in the area, causing concern about the health of the river. The soil surrounding the area has low permeability, meaning the rain and melting snow does not soak into the earth but pours on top and into the streams and river. Toxins flow into the river and helps heat the water, particularly in summer, causing environmental damage. It is part of 21 Acres' mission to correct this impact and teach other farmers and developers how to do likewise. Bank native vegetation restored. (Author photo. While middle to high-density housing projects grow up along certain stretches of the river, there is no chance that 21 Acres will be directly impacted. The Farmland Preservation Program protects the wide floodplain area in the middle and upper portions of the river for farming uses in perpetuity. . The only river use besides agriculture here is parks and the Sammamish River Trail. Part of the effort to restore and preserve the river and adjacent land is the rebuilding of bridges to allow trail access and the replanting of the riverbanks with native vegetation. NLH 3-12-08 8706 words