Truth - RS Unit 1 - Victoria County History

advertisement

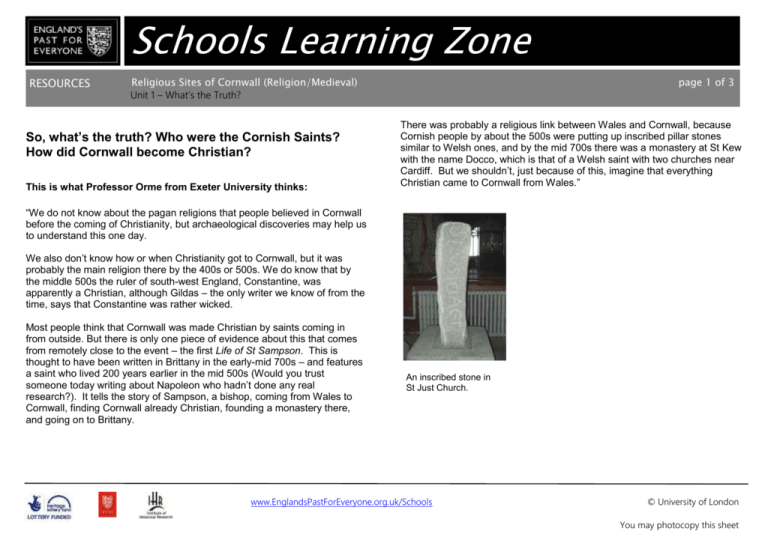

Schools Learning Zone RESOURCES Religious Sites of Cornwall (Religion/Medieval) Unit 1 – What’s the Truth? So, what’s the truth? Who were the Cornish Saints? How did Cornwall become Christian? This is what Professor Orme from Exeter University thinks: page 1 of 3 There was probably a religious link between Wales and Cornwall, because Cornish people by about the 500s were putting up inscribed pillar stones similar to Welsh ones, and by the mid 700s there was a monastery at St Kew with the name Docco, which is that of a Welsh saint with two churches near Cardiff. But we shouldn’t, just because of this, imagine that everything Christian came to Cornwall from Wales.” “We do not know about the pagan religions that people believed in Cornwall before the coming of Christianity, but archaeological discoveries may help us to understand this one day. We also don’t know how or when Christianity got to Cornwall, but it was probably the main religion there by the 400s or 500s. We do know that by the middle 500s the ruler of south-west England, Constantine, was apparently a Christian, although Gildas – the only writer we know of from the time, says that Constantine was rather wicked. Most people think that Cornwall was made Christian by saints coming in from outside. But there is only one piece of evidence about this that comes from remotely close to the event – the first Life of St Sampson. This is thought to have been written in Brittany in the early-mid 700s – and features a saint who lived 200 years earlier in the mid 500s (Would you trust someone today writing about Napoleon who hadn’t done any real research?). It tells the story of Sampson, a bishop, coming from Wales to Cornwall, finding Cornwall already Christian, founding a monastery there, and going on to Brittany. An inscribed stone in St Just Church. www.EnglandsPastForEveryone.org.uk/Schools © University of London You may photocopy this sheet RESOURCES Religious Sites of Cornwall (Religion/Medieval) page 2 of 3 Unit 1 – Legends of the Cornish Saints “All the other information we have about the saints is much later. One source for it is place-names like St Austell, St Columb Major, Gwinear, and so on, which are based on people’s names – people who were later thought of as saints. Even the place-names are mostly not recorded until from after about 900. Some of the names are those of Breton and Welsh saints, like Winwaloe at Landewednack and David at Davidstow. These names were probably borrowed from other places. It’s not very likely that the people concerned ever came to Cornwall and founded those churches. If we look at the churches dedicated to Piran and Petroc in Cornwall, Wales and Brittany, it is much more likely that both these saints originated in Cornwall than came from elsewhere. Their main centres, where they were especially respected, were at Perranzabuloe (Piran), Bodmin and Padstow (Petroc). These churches became so famous that other countries tried to adopt these saints as their won. In the 1200s in Ireland, for example, a whole 700 or 800 years after he is supposed to have lived, people tried to make Piran into an Irish saint by saying that Ciaran in Irish is the same as Piran. The life of St Ciaran was then rewritten to be the life of St Piran. This was all untrue.” Other saints’ names are unique to Cornwall, or are likely to have started in Cornwall and spread to Brittany and Wales, like Piran and Petroc. The other source is the Lives of Saints written in Brittany, Cornwall, and Wales from the late 800s onwards. There’s no evidence that the writers of these lives had any information we don’t. They wanted to explain who the people like Austell, Columb, and Gwinear were. They did this by describing them in the way people expected saints to be. So the saints’ stories almost always say that the saint came from somewhere else (like Sampson was said to have done), was a holy man or woman, founded a church, did miracles, and sometimes got martyred (killed for their beliefs). Historians now think that most of these saints were important local people. Some were buried in burial grounds and the burial grounds came to be named after them; later on, churches were built on the burial grounds and came to have the same names. Others may have actually founded a church. Some were probably clergy, but others noblemen or women. They may not have been particularly saintly, and there is no evidence that any of them was ever martyred. Bodmin Church. www.EnglandsPastForEveryone.org.uk/Schools © University of London You may photocopy this sheet RESOURCES Religious Sites of Cornwall (Religion/Medieval) page 3 of 3 Unit 1 – Legends of the Cornish Saints So what can we say for certain? “We should probably imagine Cornwall, southern England, Brittany, and Wales as all closely linked (Devon was British-speaking until about the 700s), and all sharing their religion, with some people going to and fro between all of them. We should not think of the Cornish as a passive people who simply got their religion from elsewhere. Still, the lives of the Saints are important – not because they are true, but because people thought they were true later on. Although Cornwall became part of England in the late 800s and early 900s, people in Cornwall went on imagining themselves as linked historically with Ireland, Wales, and Brittany rather than with England. To that extent, at least, they saw themselves as different from the English.” www.EnglandsPastForEveryone.org.uk/Schools © University of London You may photocopy this sheet