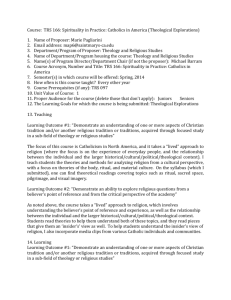

THE THEOLOGY OF ECOLOGY —a review article of: Celia Deane

advertisement

THE THEOLOGY OF ECOLOGY —a review article of: Celia Deane-Drummond, ECO-THEOLOGY, London (Darton Longman and Todd: 2008). Donal Dorr Ecology has become a topic of major general interest in recent years. It is not surprising, then, that a lot of work has been done on various aspects of an ecological spirituality. But a spirituality of ecology needs to be grounded in a solid and widely-accepted theology. I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that as yet we do not have such a generally-recognised theology. In fact the theology of ecology has largely remained on the sidelines of theological studies. Perhaps the main reason for this is that a genuinely ecological perspective requires such a radical re-visioning of the whole body of traditional theology that many of the more established theologians are unwilling to undertake it. It calls for a shift from an almost exclusive focus on the relationship between God and humanity, to a perspective which takes the whole process of evolution far more seriously and situates humans in the much wider context of the billions of years’ history of our universe. Furthermore, a lot of the new thinking in this area comes from feminist theologians. The fact that some of these writers have used goddess language or Gaia language may have led mainstream theologians to neglect or marginalize the whole topic. Most of the current writing on ecology sets out to raise our awareness and invites us to take an ethical stance on such issues as global warming and genetic modification. Celia Deane-Drummond, professor of theology and the biological sciences at the University of Chester, has written a very different kind of book. It is true that she devotes the first two chapters to a wide-ranging but condensed survey of these and other pressing practical ecological issues; and she has a short postscript on ‘eco-praxis’. But the intervening ten chapters offer us a very thorough exploration of the strictly theological issues in ecology—for instance: its biblical basis; its Christological dimension; how ecological theology relates to trinitarian theology; how dreadful pain in the non-human world and in the process of evolution can be reconciled with God’s love and care for all creation; and whether or to what extent non-human creatures are to partake in the renewed creation at the end of the world as we know it. This book is a very valuable resource for students and for any reader who has a serious interest in the topic. In some respects it is an introduction to the various important and difficult theological topics the author explores. But as I waded through some of the more dense material it felt at times more like an advanced-level course. The general reader could perhaps feel swamped at times by the summaries and critical evaluations by Professor Deane-Drummond of the views of so many different authors. The book has the feel of one written on the basis of the author’s class-notes for a year-long course of lectures. I say this not as a criticism but to convey a sense of the kind of book it is. Indeed I would have loved to have had the opportunity to sit in on her lectures and take part in the dialogue which they must have stimulated. I have the impression that she could have written a whole book about the material she covers in each of the twelve chapters and the postscript. In fact she already has written extensively about most of these topics in previous works—as indicated by the five books and various articles listed under her name in the bibliography. Because she has set out to cover so much material in one relatively short book (185 pages apart from notes etc), some of her summaries of the views of other theologians are so 1 compressed and dense that they remain rather obscure; at times she merely alludes to some point which she or another author has spelled out in far more detail in some other study (e.g. p. 50 at note 19, p 112 at note 56; p. 120 at note 29; p.155 at note 48). Professor Deane-Drummond covers so much material in this book that I found I had to take it in slow stages. I would advise readers to spread their reading and study of it over several months, just as though they were Professor Deane-Drummond’s students following her course. This would allow them to focus on one chapter and one topic at a time, not just reading what she has to say but also consulting some of the many books and sources which she refers to in each chapter. When I was a teenager some slightly disreputable booksellers sold line-by-line translations of Latin and Greek texts and brief summaries of the books we were supposed to study. These could be used by lazy students to avoid the work they were supposed to do for themselves. There is a danger that the present book could be used in somewhat the same way by students or interested readers. So they would be allowing Professor Deane-Drummond to do all the work of critical evaluation of the many authors whose work she summarizes. The result could be the very opposite of what the author would wish. The readers would gain a rather superficial familiarity with the many topics she covers but would not have taken time to really ‘let it in’ and to reflect on all the implications of the material she covers in the book. It is evident that she wants to avoid this kind of short-cutting by students and other readers, because she provides lists of books and articles for further study at the end of each chapter and, towards the end of the book, she devotes three pages to offering sets of questions for discussion in relation to each of her chapters. There are 34 pages of useful endnotes in the book. What a pity that these notes did not take the form of footnotes. I found it quite irritating to have to turn so frequently to the end of the book to consult the notes. Following on from these remarks about the book in general I now go on to comment briefly on some of the topics covered in individual chapters. There is a treasure-trove of useful information on ecological issues in the first chapter. There are also plenty of references to sources for more detailed background on the dozens of problems she treats—for instance, how oceans could change from being carbon ‘sinks’ to carbon emitters (p. 5), and how a tenfold increase in pesticides has not reduced the loss of crops to pests (p. 11). The author also has interesting comments on the difficulty of moving from factual knowledge of how ecosystems work to value-judgements about how we ought to behave (p. 12). ‘Economics and environmental justice’ is the topic in the second chapter. Especially useful here is Professor Deane-Drummond’s account of the problems associated with genetic modification of organisms and her treatment of the issue of the patenting of life-forms. Towards the end of this chapter she offers an interesting evaluation of the two major theories of justice—that of John Rawls and that of Amartya Sen. The origins and development of ‘Deep Ecology’ is dealt with helpfully in the third chapter. Here and in later chapters there are short summaries of the views of the main authors in the various fields she surveys—for instance, in this chapter the views of Teilhard de Chardin and Thomas Berry. In doing this Deane-Drummond shows that she is a very good teacher. The corresponding disadvantage is that these authors, or their committed disciples, may feel that her summaries and especially her brief critiques of their positions do not do always do full justice to the views of the authors she summarizes. 2 Her next topic is the relationship between ecological theology and liberationist and indigenous theologies, including a rather brief treatment of the work of Sean McDonagh. In chapter 5 she focuses on the approach of the Eastern Orthodox where liturgy has a central role. Here too she introduces the ideas of Divine Sophia and creaturely sophia, which seem to be central to her own approach. I found the material in the following chapter quite dense, perhaps because some of it is a condensed version of a more extended study published elsewhere by the author. The treatment of the biblical material in Chapter 7 is very helpful and practical—and at times quite inspiring. She offers a rich and satisfying response to the common accusation that the command in Genesis to ‘subdue’ the earth gives rise to an exploitative attitude. Particularly interesting is her suggestion that chapters 38 to 41 of the Book of Job indicate that the Earth has an intrinsic value quite independent of humans (p. 86). I also like her idea that the Wisdom books provide a link between the vertical and the horizontal strands in an ecological theology (p. 93). A further valuable point is her insistence that God’s ‘rest’ on the seventh day of creation is not something passive but rather an active appreciation of the earth not just as ‘good’ but also as ‘holy’ (p. 96). The first few pages of Chapter 8 on Christology are very interesting and helpful. Then she goes into a rather more detailed account and critique of the views of Matthew Fox, Teilhard de Chardin, Jürgen Moltmann, and others; I found this material rather heavy. But I found the final few pages of this chapter quite valuable—especially her account of how Colossians 1:13-22 shows that all of creation is caught up in both the creative and redemptive work of Christ as the incarnate Wisdom (pp. 111-2). Theodicy is the topic in Chapter 9. Here the author bravely faces the really difficult issues about evil in the human and non-human world—and bravely admits that there is no fully satisfying answer. One particularly helpful point is her suggestion that in between physical evil and moral evil we should add a third category, namely, anthropogenic evil, that is, evil caused by humans but suffered in the non-human world e.g. industrial pollutants which have devastating impacts on other species (p. 116). Also helpful is her remark that ‘an empathetic God is not necessarily the same as a suffering God’; and her suggestion that ‘perhaps the pain that humanity experiences in witnessing the suffering of other species is in a sense a sharing in Divine compassion’ (p. 122). In the final four pages of this chapter she proposes her concept of ‘shadow sophia’. I sense that, in a book of this type, she is reluctant to devote a lot of space to her own view, and the result is that it is not spelled out in adequate detail. ‘Ecology and Spirit’ is the title of Chapter 10. Here we find more of the author’s own views. She gives a cosmic role to the Spirit as well as to the Word and links both of them to Wisdom. The eleventh chapter, dealing with ecofeminist theology is one of the more difficult chapters in the book but also one of the more valuable. It offers a way through the bewildering variety of approaches by feminist writers who link ecological and feminist theology. Some of these authors use goddess language and several make use of the notion of Gaia in one way or another. Professor Deane-Drummond is quite critical of much of the writing in this area. In this chapter, as elsewhere in the book, she offers a thoroughly orthodox Christian theology, solidly rooted in the bible, while at the same time offering a feminist corrective to traditional theological language. But in this chapter I found myself getting rather lost in the detail of her analysis and critique of the views of other authors. Furthermore, I found her account of the 3 role of Sophia somewhat truncated and allusive—which is quite understandable since she was attempting to summarize the much more extended account of this topic which she has published previously. Eco-eschatology is the difficult topic dealt with in the final chapter. She is (rightly) more reticent about what it involves than are several of the authors (including Hans Urs von Balthazar, Jürgen Moltmann, and John Haught) whose views she summarizes and critiques. Being not only solidly orthodox but also eminently sensible she is inclined to agree with those who maintain that in the renewed creation God will not feel it necessary to resurrect every mosquito that ever lived. She thinks it sufficient that creatures with little or no selfconsciousness be ‘inscribed’ in the memory of God. For myself, I prefer to be even more agnostic than she is on the whole question of what the new creation will look like. Nevertheless, I found it useful to have her lead me through this speculative territory. Not because it gave me a clearer sense of what the final fulfilment of our world will look like, but because it made me more aware of the mystery that is God’s relationship with our world, and of the gift of faith that invites me to hold on in the face of this mystery. Having been led by the author through such an extended exploration of difficult theological topics I found myself comforted by the final paragraph of her postscript. There she stresses the importance of a spirit of contemplation nourished by spending time in the natural world. My overall impression of the book is that it provides us with a quite detailed map of the territory of eco-theology which we may wish to explore—and also with a reliable compass to guide us on this journey of exploration. But I remind myself that a map and a compass, however useful, are not a substitute for a personal journey through the territory. And what better place to begin the journey, or to continue it, than with some of the other books or articles by Professor Deane-Drummond which are listed in the bibliography. 4