Depression_child_review_2008

advertisement

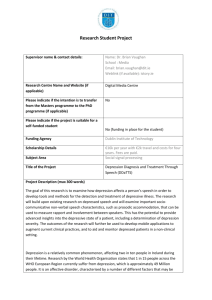

Depression 1 Carr, A. (2008). Depression in young people: Description, assessment and evidence-based treatment, Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 11, 3-15. Depression 2 Depression in Young People: Description, Assessment and Evidence-Based Treatment Alan Carr Running head or short title: Depression Keyword: Childhood depression Correspondence to Professor Alan Carr, School of Psychology, College of Human Sciences, John Henry Newman Building, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland. Tel: +353-1-716-8740 (Direct) 716-8120 (Secretary) Fax: + 353-1-716-1181. email: alan.carr@ucd.ie Revised and resubmitted in June 2007 to: Jacquelyn Dick, Assistant Editor, Developmental Neurorehabilitation, pdr@staffmail.ed.ac.uk, www.informaworld.com/devneurorehab; David Johnson, The Department of Child Life & Health, The University of Edinburgh, 20 Sylvan Place, Edinburgh, EH9 1UW, e-mail: David.Johnson@ed.ac.uk Depression 3 ABSTRACT Objective. The literature on depression in children and adolescents was reviewed to provide an update for clinicians. Review process. Literature of particular relevance to evidence-based practice was selected for critical review. Meta-analyses and controlled trials were prioritized for review along with key assessment instruments. Outcomes. An up-to-date overview of clinical features, epidemiology, prognosis, aetiology, assessment and intervention was provided. Conclusions. Depression in children and adolescence is a relatively common, multifactorially determined, and recurring problem which often persists into adulthood. Psychometrically robust screening questionnaires and structured interviews facilitate reliable assessment. There is growing evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy, psychodynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy and family therapy in the treatment of paediatric depression. There is also evidence that SSRIs may be particularly effective for severe depression, although they may carry the risk of increased suicidality. Depression 4 CLINICAL FEATURES A major depressive episode in children and adolescents is characterized by a period of low mood of at least two weeks duration, accompanied by other cognitive and behavioural features. The primary symptom of depression is low mood and / or loss of interest in daily activities including those that youngsters normally find enjoyable. There may be diurnal variation in mood, with mood being lowest in the morning. In adolescents, in some instances, irritable, rather than low mood may be the central feature. The principal cognitive features of depression are poor concentration, poor attention and indecisiveness; low self-esteem; pessimism; suicidal ideation or intent; and feelings of worthlessness or guilt. Fatigue; psychomotor retardation or agitation; and sleep and appetite disturbance are the main behavioural features. The diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode from ICD 10 [1] and DSM IV TR [2] and are given in Table 1. Major depression is an episodic disorder characterized by major depressive episodes and intervening periods or normal mood. This is distinguished from dysthymia, which is a milder but more persistent mood disorder, characterized by chronic low mood for at least a year (in young people and 2 years in adults), accompanied by fewer additional cognitive or behavioural symptoms than are required for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. For a DSM diagnosis only two additional symptoms are required and for and ICD diagnosis 3 additional symptoms are required for a dysthymia diagnosis. In both DSM IV TR and ICD 10, children and adolescents are diagnosed using almost the same criteria employed as are used for adults. There are some noteworthy minor differences. In DSM IV TR, irritability and failure to make expected weight gain count as symptoms of major depression in children, but not adults; and the duration of symptoms in dysthymia need only be 1 year for a diagnosis to be made in children compared with a duration of 2 years in adults. In view of the evidence that developmental changes in depressive symptoms and the overall depressive syndrome occur during Depression 5 childhood and adolescence, more extensive modifications to adult criteria have been proposed [3,4]. Luby [3] in a series of studies aimed at revising DSM IV TR criteria for preschoolers found that preschool children express depressive symptoms in thematic play, and through loss of interest in play. Also she has shown that a more valid definition of the depressive syndrome in preschoolers requires the presence of 4 (and not 5) symptoms, most of the time (not all of the time) over a 2 week periods as specified in DSM IV TR. Weiss & Garber [4] in a meta-analysis of 16 studies of depressive symptoms in children of different ages found that anhedonia, hopelessness, hypersomnia, weightgain and social withdrawal are rarer in younger children but become more common as children mature. In clinical practice, it is important to take account of these developmental issues in assessing depression in children and adolescents. EPIDEMIOLOGY Depression in young people is not a rare condition. In a review of 18 epidemiological studies of community samples, Costello et al., [5] found prevalence rates of major depression in youngsters under 18 to range from 0.2-12.9%, with a median of 4.7%. Depression is more common among adolescents than children; more common among teenage girls than boys; and very common among clinical populations [6]. Community studies of depression co-morbidity rates, show that high rates of co-morbidity occur with anxiety disorder, conduct disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood and with eating disorders and substance abuse in adolescence [5, 7]. PROGNOSIS While the majority of youngsters recover from a depressive episode within a year, they do not grow out of their mood disorder [6]. Major depression is a recurrent condition and depressed youngsters are more likely than their non-depressed counterparts to develop episodes of depression as adults, although they are no more likely to develop other types Depression 6 of psychological problems [8]. Double depression: that is, chronic dysthymia combined with major depressive episodes; severe depressive symptoms; maternal depression; comorbid conduct disorder or drug abuse; family problems; and social adversity have all been shown in longitudinal studies to be predictive of worse outcome [6, 8, 9]. In a large North American community study, Lewinsohn et al. [10] found that 12% of adolescents with depression relapsed within a year and 33% within 4 years. Interepisode intervals decrease as more episodes occur. This may be due to the neurobiological process of kindling [11] and the cognitive process of rumination [12, 13]. According to cognitive therapists, small stresses, which lead to small negative mood changes, can give rise to chronic rumination and catastrophising and precipitate later episodes of depression. According to neurobiological theorists, multiple episodes of depression, through a process of kindling, probably render the neurobiological systems that maintain depression more vulnerable to depressogenic changes in response to minor stresses. Children and adolescents with depression are at a higher risk of suicide than youngsters with other disorders, so the assessment and management of suicide risk is a priority when dealing with depressed young people [14,15,16]. SEX DIFFERENCES In adulthood twice as many women have depression as men. This sex difference in depression rates begins after the onset of puberty. Hankin and Abramson [7] have argued that multiple constitutional, personal and contextual factors may account for this, and have drawn support for their position from a review of a considerable body of empirical evidence. What follows are some key findings of their extensive review. Girls experience more independent and dependent stressful life events than boys. Independent life events are outside the individual’s control, for example, bereavement. Dependent life events are Depression 7 elicited by the individual’s behaviour, for example, interpersonal rejection. Girls also ruminate more and have a more depressive inferential style in response to these events. Girls have higher levels of the personality trait –neuroticism – which is a vulnerability factor for depression and which is partially genetically determined. Finally, genetic factors may render teenage girls more vulnerable to depression than boys. For example, in a study of 377 depressed and non-depressed adolescents exposed to high and low levels of life stress, Eley and colleagues [17] found that for girls (but not boys), depression occurring during exposure to high stress was associated with a specific molecular genetic deficit, 5-HTTLPR, a short allele form of the promoter region of the serotonin transporter 5-HTT. Collectively, the aggregation of these factors, reviewed by Hankin and Abramson [7] . may partly explain the higher rates of depression in teenage girls. AETIOLOGY Research on the aetiology of depression is converging in support of a diathesis-stress model [18, 19]. Children and adolescents are rendered neurobiologically vulnerable to depression by genetic factors which interact with environmental factors to give rise to mood disorders. Neurobiological vulnerability to depression is polygenetically determined [20]. The genes associated with this vulnerability are different in males and females [21]. Genetic factors play an increasingly significant role in the aetiology of depression with the transition to adolescence, particularly in girls [22]. Genetic factors may render young people vulnerable to depression by affecting their temperament and personality, and by affecting neurobiological factors associated with depression. Genetic factors influence the level of the personality trait, neuroticism, which is a predisposing factor for depression [23]. Genetic factors may also influence the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis, and the functioning of the serotonin, cholinergic and noradrenergic systems, which show deregulation under stress in depression [24]. Depression 8 Environmental factors which place undue stress on youngsters; which outstrip their coping capacities; and which occur in the absence of social support, interact with genetic factors and may initially render youngsters psychologically vulnerable to depression. Later they may precipitate the onset of depressive episodes and prevent recovery or precipitate relapse [25]. Loss of important relationships, failure experiences, bullying, illnesses and injuries, and disruptive life transitions such as moving house or the onset of puberty all constitute stressful life events. There is some evidence that stressful events are more likely to precipitate depression when they occur in the same domain as those that rendered the individual vulnerable to depression earlier in their lives. So youngsters who suffered interpersonal losses in early childhood are more likely to have a depressive episode later in their development precipitated by an interpersonal loss, and those that experienced significant achievement failures early in life are more likely to become depressed when they experience failure in academic and work domains later in their development [26, 27]. Non-optimal early parenting environments are particularly important sources of environmental stress, and deserve special mention. Non-optimal parenting environments include those characterized by lack of parental attunement, parental psychopathology (notably maternal depression and paternal substance use), family conflict, stressful parental separation, domestic violence, and child maltreatment, all of which may be influenced by wider sociocultural factors such as poverty and social isolation [19]. Non-optimal parenting environments may render youngsters psychologically vulnerable to depression by contributing to the development of poor skills for regulating negative emotional states and coping with both minor daily stresses and larger stressful life events [28]; self-criticism [26]; a low sense of control over one’s life [29]; a pessimistic cognitive style [30]; a negative and hopeless inferential style [31]; a ruminative response style [32]; insecure attachment styles [33]; and poor skills for developing supportive social networks [19, 34]. Depression 9 Once an episode of depression occurs it may be maintained at a psychological level by all of these personal psychological factors; and also by neurobiological processes, life stresses and non-optimal parenting environments mentioned earlier. On the positive side, personal and contextual protective factors may reduce the likelihood of depression or contribute to recovery. These include intelligence, problemsolving skills, an active coping style, the capacity for self-reflection, self-esteem, an internal locus of control and sense of mastery, higher levels of physical activity, good social skills, a supportive cohesive family, a positive school environment, supportive peer relationships, and a supportive community [19, 35, 36] ASSESSMENT Assessment for depression should begin with a broad screening for psychological difficulties. If this suggests that there are mood problems, a more detailed assessment of depressive symptoms may be conducted. If appropriate, this may be followed by structured interviewing about depressive syndromes. Then a wider interview covering risk and protective factors mentioned in the previous section, along with suicide risk assessment should be conducted. Guidelines for such broader interviews are given in Carr [15, 37] and elsewhere [14, 16, 38, 39]. For screening school-aged children and adolescents for any type of psychological disorder, including depression, the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) [40, 41] and the Behavioural Assessment System for Children (BASC) [42] are very useful. These are both reliable, valid and well standardized multi-informant assessment packs, which contain parent, teacher and child report forms, and which assess a wide range of emotional and conduct problems including depression. However, because these instruments span a wide range of problems, the depression subscales Depression 10 included in them, contain only a small number of items. If children screen positive for mood disorders on BASC or ASEBA depression scales, it is appropriate to conduct a more detailed assessment of depressive symptoms. The most widely used and best validated self-report instruments for assessing depressive symptoms in children are the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [43], the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth (BDIY) [44] and the Reynolds Child and Adolescent Depression Scales (RCDS and RADS) [45, 46]. The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire [47] has parent and self-report versions, and is the most widely used and best validated screening instrument with this feature. For preschool children, the parent-report Preschool Feelings Checklist [48] is one of the very few available measures for screening toddlers for depression. All of these instruments have good internal consistency and testretest reliability. They also have strong criterion validity, distinguishing between groups of cases with and without a diagnosis of depression [43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48]. These instruments are useful for evaluating symptom severity, and changes in symptom severity over time. However, unlike structured interviews they do not evaluate depressive syndromes as conceptualized in DSM IV TR and ICD 10. Where young people obtain elevated scores on depressive symptom assessment instruments, it is appropriate to conduct a structured interview to assess depression from a syndromal perspective. There are many structured interviews for assessing depression (and other DSM IV TR or ICD 10 disorders), most of which have parent and child-report versions, or which allow for data from multiple informants to be combined. In the UK the most widely used is the Development and Well-being Assessment (DAWBA), [49]. In North America, for school aged children, some of the most widely used include the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) [50], the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) [51], the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) [52] and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children (KSADS) [53]. The Berkeley Puppet Interview [54] may be used for assessing preschool Depression 11 children. The Young-Child DISC-IV [55] and the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) [56] are parent report interviews for use with children under 6. These instruments all have moderate to good inter-rater reliability [49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. The mood disorders module from these instruments may be used obtain a reliable diagnosis of depression. TREATMENT EFFECTIVENESS Available information on the natural history of childhood and adolescent depression provides a context for interpreting the results of treatment trials of psychological therapies. The majority of youngsters recover from a depressive episode within a year; about a tenth relapse during the following year; about a third relapse within 4 years; and inter-episode intervals decrease as more episodes occur [10]. Depression often persists into adulthood [8], and it is a risk factor for suicide [15]. Treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) is ineffective [57], and treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be associated with increased suicide risk in adolescents [58, 59], although there is some evidence to the contrary [60]. There is clearly a strong case for the importance of developing effective psychotherapies for depression in children and adolescents. In selecting treatment outcome literature for review, priority was given to metaanalyses and systematic reviews, and in their absence to randomized controlled trials. Where these types of evidence were not available, outcome studies that included a matched control group or a single treatment group were included, but results of such studies were interpreted with appropriate caution. In the most comprehensive available meta-analysis of 35 randomized controlled studies of psychotherapy for child and adolescent depression, Weisz et al. [61] obtained an effect size of .34. This indicates that the average treated case fared better than 63% of untreated cases and is equivalent to a success rate of about 58%. This modest effect size is more valid than the larger effect size of .72 found by Michael and Crowley [62] in an Depression 12 earlier, smaller and less methodologically robust meta-analysis of 14 trials of psychotherapy for child and adolescent depression. Weisz et al. [61] also found that there were no significant differences in outcome between cognitive behavioural treatments and other treatments, or between treatments conducted under optimal or routine clinical conditions. Treatment gains were maintained at 6 months follow-up but not at 1 year follow-up. This is not surprising giving the episodic and recurrent nature of major depression. In addition to these omnibus reviews of the overall effectiveness of psychotherapy for depression in young people, a number of reviews focusing on specific forms of treatment, and a number of key outcome studies which have examined the effectiveness of cognitive-behaviour, psychodynamic, interpersonal, and systemic therapy deserve mention. Cognitive behaviour therapy There is evidence from three reviews for the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of child and adolescent depression. In a systematic review of 6 studies of cognitive behaviour therapy for major depression in children and adolescents, Harrington et al. [63] found a remission rate of 62% for treated cases and 36% for untreated cases. In a meta-analysis of studies of cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in adolescence, Lewinsohn and Clarke [64] found a post-treatment effect size of 1.27. They also found that 63% of patients showed clinically significant improvement. In a metaanalysis of 6 studies of cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in adolescence, Reinecke et al. [65] obtained a post-treatment effect size of 1.02 and a follow-up effect size at 6-12 months of .61. Collectively these results indicate that just over 60% to just over 70% of young people diagnosed with a depressive disorder benefited from cognitive behaviour therapy. In an important comparative trial Brent [66] and his team found that immediately after treatment, more youngsters who received cognitive behaviour therapy (60%) were in Depression 13 remission compared with those who received family therapy (38%) or supportive therapy (39%). However, at two years follow-up there were no significant differences between the outcomes of the 3 groups. Recovery rates were 94% for cognitive behaviour therapy, 77% for family therapy, and 74% for supportive therapy. In all three groups, a negative family environment characterized by maternal depression and family conflict on the one hand, and severe cognitive distortions and depressive symptomatology on the other, were associated with poorer outcome. The positive effects of cognitive behaviour therapy arose predominantly from changes in depressive cognitive distortions. Positive changes in family functioning accounted for improvements in the family therapy group. In all three groups a rapid improvement during the first couple of sessions occurred in just over a third of cases, and was predictive of a positive outcome. Therapeutic factors common to all three types of therapy, such as the quality of the therapeutic alliance, probably accounted for this rapid improvement. All participants in this study received 12-16 sessions. During the follow-up period 62% used other services for depression, 33% for family problems, and 31% for conduct problems. The results of the study suggest it may be worthwhile combining individually-oriented cognitive behaviour therapy and family therapy to aim to address both intrapsychic and interpersonal depression maintaining factors, and to extend therapy beyond 16 sessions so that additional services are not required. Cognitive behaviour therapy for depression rests on the hypothesis that low mood is maintained by a depressive thinking style and constricted lifestyle that entails low rates of response contingent positive reinforcement. Cognitive behaviour therapy programmes for adolescents evaluated in treatment trials have two main components which target these two maintaining factors: behavioural activation and challenging depressive thinking [67]. In challenging depressive thinking, youngsters learn mood monitoring, and how to identify and challenge depressive negative automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions that accompany decreases in mood. With behavioural activation youngsters re-organize their daily routines so they involve more pleasant events, physical exercise and social Depression 14 interaction. They also develop skills to support this process including social skills, relaxation skills, communication and problem-solving skills, and relapse prevention skills. Some cognitive behavioural programmes for depression in young people include concurrent intervention with parents, which helps them understand factors that maintain depression and support youngsters in following through on the behavioural activation and cognitive components of the child-focused part of the programme. Cognitive behaviour therapy usually spans 10-20 child-focused sessions and may be offered on an individual or group basis. Where concurrent parent sessions occur, usually about 5-10 of these are offered. Lewinsohn’s group-based programme [68, 69] and Brent’s [66] and Weisz’s [70] individual cognitive behaviour therapy programmes are good examples of well-developed North American evidence-based approaches in this area. In the UK, Stallard’s Think Good - Feel Good programme offers a best practice approach to CBT with young people [71, 72] Psychodynamic therapy One randomized controlled trial and one non-random matched group trial provide evidence for the effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapy with depressed children and adolescents [73, 74]. In a randomized controlled study of 72 youngsters aged 9-15 assigned to psychodynamic or family therapy, Trowell et al. [73] found that about 75% of cases in both groups were fully recovered after therapy. 100% of those who received psychodynamic therapy and 81% of those who received family therapy were fully recovered at 6 months follow-up (but this group difference was not significant). Psychodynamic and family therapy also led to a significant reduction of double depression (major depression with co-morbid dysthymia) and rates of other co-morbid conditions. In this study psychodynamic therapy involved an average of 25 individual sessions and 12 concurrent parent sessions spanning 9 months, following a manual based on Malan [75] and Davenloo’s [76] model of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy. In this model the focus Depression 15 is on interpreting the links between defences, anxiety and unconscious feelings and impulses, within the context of the transference relationship with the therapist, the relationship with significant people in the child’s current life, and early relationships with parents or caregivers. Family therapy involved an average of 11 sessions spanning 9 months based on Byng Hall [77] and Will and Wrate’s [78] integrative model of family therapy (discussed in more detail below). In a non-randomized matched group study of 58 children aged 6-10 years, most of whom had dysthymia, assigned to psychodynamic therapy or community-based treatment as usual, Muratori et al [74] found that at two years follow-up, 66% of those who received psychodynamic psychotherapy were recovered compared with 38% in the control group. In this study, psychodynamic therapy involved 11 conjoint parent-child sessions and several additional individual sessions for children only, based on the Cramer and Palacio Espasa’s [79] model. Within this model in the first phase, parent-focused work occurs where parent-child interactions are interpreted in terms of their defensive functions. Playbased child-focused work occurs in the second phase, with the aim of helping the child understand and articulate links between feelings, wishes and symptoms. In the final phase, the core-conflictual theme that links the parent’s defensive style to the child’s symptoms is explored. A core conflictual theme has three key elements: (1) the person’s wish in a particular type of situation, (2) the person’s anticipated or imagined response of the other person in that type of situation, and (3) the person’s actual defensive response in that type of situation. Taken together, the results of these two trials provide preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy with children and adolescents. Because Muratori’s study was not a randomized controlled trial, caution is required in interpreting the results. The exceptionally positive outcome of psychodynamic psychotherapy in Trowell et al.’s [73] study is very impressive and requires replication. Depression 16 Interpersonal therapy There is evidence from three controlled efficacy studies, a controlled effectiveness study and a single group outcome study that interpersonal psychotherapy is an effective treatment for adolescent depression which leads to recovery in more than 75% of cases, and in two of these studies interpersonal therapy was found to be as effective as cognitive behaviour therapy [80, 81, 82] Interpersonal therapy for adolescent depression targets five interpersonal difficulties which are assumed to be of particular importance in maintaining depression: (1) grief associated with the loss of a loved one; (2) role disputes involving family members and friends; (3) role transitions such as starting or ending relationships within family, school or peer group contexts, moving houses, graduation, or diagnosis of an illness; (4) interpersonal deficits, particularly poor social skills for making and maintaining relationships; and (5) relationship difficulties associated with living in a single parent family. In interpersonal therapy the specific focal interpersonal factors that maintain the youngster’s depressive symptoms are addressed within a series of childfocused and conjoint family sessions. Mufson et al.’s [83] manual provides detailed guidance on this approach to therapy with depressed adolescents. Family therapy There is evidence from six studies for the effectiveness of family therapy for child and adolescent depression and suicidality, two of which have already been mentioned [66, 73]. In a comparative study, Trowell et al. [73] found that 11 sessions of family therapy was as effective as a programme which included 25 sessions of psychodynamic therapy coupled with 12 adjunctive parent sessions. 75% of cases no longer met the criteria for depression after treatment and 81% were recovered at 6 months follow-up. Byng Hall [77] and Will and Wrate’s [78] integrative model of family therapy was used in this trial. Therapy involved techniques from many schools of family therapy and helped families Depression 17 understand the links between the youngster’s depression, problematic family scripts and insecure family attachment patterns. It also helped family members develop more secure attachments to each other and re-edit problematic family scripts to form a more coherent narrative about how to manage stress and life-cycle transitions. In a controlled study of attachment-based family therapy for depression with 32 adolescents, Diamond et al. [84] found that after treatment 81% of treated cases no longer met the criteria for depression, whereas 47% of the waiting list control group did. At 6 months follow-up 87% of cases were not depressed. Attachment-based family therapy involves the following sequence of interventions which have been shown in process studies to underpin effective treatment: relational reframing, building alliances with the adolescent first and then with the parents, repairing parent-adolescent attachment, and building family competency [85]. In another comparative study, Brent’s team [66], found that only 38% of depressed adolescents were recovered immediately after family therapy, but at two years follow-up 77% no longer met the criteria for depression. Family therapy was less effective in the short-term, but as effective in the long-term as cognitive behaviour therapy. Improvements in family functioning accounted for youngsters’ recovery. A behavioural systems approach to family therapy was used in this trial. This involved using family-based behavioural interventions such as problem monitoring, communication and problem-solving skills training, contingency contracting, and relapse prevention to reduce family conflict, enhance family relationships and promote better mood management. In a controlled trial involving the families of 31 adolescents, Sanford et al. [86] evaluated the incremental benefit of adding psychoeducational family therapy to a routine treatment programme involving predominantly supportive counselling and SSRI antidepressant medication. Three months after treatment 75% of the family therapy group and 47% of controls no longer met the criteria for depression, and parent-adolescent relationships in the family therapy group were significantly better than in the control group. Depression 18 A 13 session, home-based adaptation of Falloon et al.’s [87] family therapy model was used in this study. Treatment included psychoeducation about depression, communication and problem-solving skills training, and relapse prevention. In a single group outcome study for adolescents with co-morbid depression and substance abuse, Curry et al., [88] found that after a combined programme of cognitive behavioural therapy and family therapy, 50% of cases recovered from depression and 66% from substance abuse. The programme spanned 10 weeks, with weekly family therapy sessions and twice weekly cognitive behaviour therapy group sessions. Robin and Foster’s [79] model of family therapy for negotiating parent-adolescent conflict was used in this programme. Huey et al. [90] evaluated the effectiveness of multisystemic therapy – an intervention programme that includes family therapy as its core component [81]– in a randomized controlled study of a group of with 156 African American adolescents at risk for suicide referred for emergency psychiatric hospitalization. Most of these youngsters were depressed, but had multiple other co-morbid difficulties. Compared with emergency hospitalization and treatment by a multidisciplinary psychiatric team, Huey et al. [80] found that multisystemic therapy was significantly more effective in decreasing rates of attempted suicide at 1-year follow-up. Collectively these studies lend support for both attachment-based and psyhoeducationally oriented cognitive-behavioural approaches to family therapy as effective treatments for depressed adolescents, and multisystemic therapy as an effective family therapy based approach to reducing suicidality. Antidepressant medication In a meta-analysis of 13 studies of the effectiveness of TCAs for depression in young people, Hazell et al. [57] concluded that TCAs are ineffective with children and only have a small impact on adolescent depression. In contrast, there is growing evidence that Depression 19 SSRIs may have a role in the treatment of depression in young people. In reviews of controlled trials of SSRIs for child and adolescent depression, Cheung et al. [92] and Vasa et al. [93] found a number of SSRIs, notably fluoxetine, alleviated the symptoms of depression in about two thirds of children and adolescents and led to complete remission in about a third of cases. However, because there is some evidence that SSRIs may lead to increased suicidal ideation and behaviour [58, 59], caution in required in using them in the treatment of children and adolescents with mood disorders. Results of the large USA multisite Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study [TADS, 94] which involved 439 moderately depressed adolescents, showed that cognitive behaviour therapy combined with fluoxetine (an SSRI) led to a significantly higher improvement rate (71.0%) than medication alone (60.6%), which in turn led to a significantly higher improvement rate that cognitive-behaviour therapy alone (43.2%). Cognitive behaviour therapy combined with SSRis also led to the greatest reduction in suicidal thinking, compared with the other two conditions. This may provide an evidencebased rationale for combining SSRIs with cognitive behaviour therapy in moderate depression. In the TADS study the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy alone (43.2%) was low compared with other trials where the outcome has been about 60% [53]. This may have been due to the characteristics of the participants. In an analysis of factors related to outcome in the TADS study, Curry et al. [95] found that cognitive behaviour therapy combined with SSRIs was more effective than SSRIs alone for mild to moderate depression and for depression with high levels of cognitive distortion, but not for severe depression or depression with low levels of cognitive distortion. In contrast to the results of the TADS study, Goodyer et al. [96] in the UK multicentre Adolescent Depression Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) involving 208 adolescents with severe depression who had not responded to an initial brief trial of psychotherapy, found that there was no significant benefit in terms of recovery from depression or reduction in suicidal ideation associated with adding 19 sessions of Depression 20 cognitive behaviour therapy to routine outpatient consultations at a specialist clinic and SSRIs. By 28 weeks 57% of trial participants showed clinically significant improvement including reduced suiciality. The sample in this study included cases of severe depression that would have been excluded from the TADS study because of suicidality, depressive psychosis or co-morbid conduct disorder. Goodyer, concluded that for severe adolescent depression, of the type typically referred to UK specialist services, the addition of cognitive behaviour therapy to routine specialist care and SSRI treatment confers no additional benefit. Two additional US studies have yielded similar results. In a randomized trial involving 152 depressed adolescents, Clarke et al. [97] found that the addition of cognitive behaviour therapy to routine treatment with SSRIs had a negligible impact on the course of depressive symptoms. In a randomized multisite trial involving 73 moderately depressed adolescents, Melvin et al. [98] found that treatment with SSRIs (sertraline), cognitive behaviour therapy and both combined had similar outcomes 6 months after treatment. The results of the studies reviewed in this section support the use of SSRIs in severe depression in young people, when they do not respond to a brief trial of psychotherapy. However, because there is some evidence that treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be associated with increased suicide risk in adolescents [58, 59], regular monitoring of this is essential. Electro convulsive therapy There are currently no data from controlled trials to support the use of electroconvulsive therapy with adolescents, but some limited data from open trials, so its use remains cautious and controversial [99, 100, 101, 102]. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE Depression 21 The evidence reviewed in this paper has implications for assessment and treatment. Assessment for depression should begin with a broad screening for psychological difficulties with instruments such as those in the ASEBA or BASC evaluation packs. If this suggests that there are mood problems, a more detailed assessment of depressive symptoms may be conducted with depression-specific instruments such as the CDI, BDIY, RCDS or RADS. Where elevated scores on these occur, it is appropriate to conduct a structured interview to assess depression from a syndromal perspective with the mood disorders module from instruments such as the DAWBA, DISC-IV, DICA, CAPA, or KSADS. If children are under 5 the Young-Child DISC-IV or PAPA may be used. These structured interviews will yield DSM or ICD diagnoses. Then a wider interview covering risk and protective factors mentioned in the previous section, along with suicide risk assessment should be conducted. With regard to treatment, the conclusions that can be drawn are limited by the nature of available evidence. For example, only tentative conclusions may be made about how to tailor treatment to match client characteristics because for all forms of therapy, evidence is available for only a limited range of children in terms of age, socio-economic status, family composition, depression severity, comorbidity and so forth. For example, in Trowell et al.’s [73] trial of psychodynamic therapy, only children over 9 were included, and this is the only randomized controlled trial of psychodynamic therapy. Also, actively suicidal cases were excluded from most psychotherapy trials, with the exception of Goodyer et al’s [96]. Tentative conclusions must also be drawn about how best to combine child-focused and parent-focused interventions, since no treatment deconstruction trials have been conducted in which child-focused, parent-focused and combined treatment protocols have been compared. With these caveats in mind, the following guidance is offered for clinical practice until more evidence becomes available. Effective protocols for mild to moderate depression have been developed within the cognitive-behavioural, interpersonal, psychodynamic and family therapy traditions. These Depression 22 protcols should be flexibly applied in clinical practice, taking due account of clinical formulations of clients’ unique profiles of personal and contextual predisposing, precipitating, maintaining and protective factors. In light of such clinical formulations, a case may be made for combining child and family based components of treatment protocols that have been shown to be effective, to address specific elements within a client’s formulation [37]. Extant evidence suggests that family-based intervention for child and adolescent depression includes family psychoeducation; facilitating family understanding and support of the depressed youngster; and organizing home-school liaison to help the youngster re-establish normal home and school routines. Available evidence suggests that child-focused interventions involves exploration of contributing factors, some of which may be outside youngsters’ awareness; facilitating moodmonitoring; increasing physical exercise, social activity and pleasant events; modification of depressive thinking styles, depression maintaining defence mechanisms and depression maintaining patterns of social interaction; the development and use of social problem-solving skills; and the development of relapse prevention skills. Extant evidence suggests that a dozen family sessions and twice as many individual sessions are probably necessary for treating mild to moderate depression in children and adolescents. With severe depression, where clients show no response to a brief trial of psychotherapy, and where they present with suicidality, psychotic features, or comorbid difficulties, a trial of SSRIs combined with routine specialist clinical monitoring and support is the treatment of choice. However, caution is warranted in using SSRIs with youngsters, since they may increase suicide risk. These conclusions are broadly consistent with international guidelines for best practice [38, 39], but differ from UK NICE guidelines insofar as these do not recommend the use of psychodynamic therapy for depression. _____________ Depression 23 REFERENCES 1. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992. 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition-Text Revision. DSM –IV-TR. Washington, DC: APA; 2000 3. Luby J. Affective disorders. In: Delcarmen-Wiggens R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant and toddler mental health assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 337-353. 4. Weiss B, Garber J. Developmental differences in the phenomenology of depression. Developmental Psychopathology 2003; 15: 403-30. 5. Costello E, Mustillo S, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. In: Luborsky L, Petrila J, Hennessy, K, editors, Mental health services: A public health perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 111-128. 6. Costello EJ, Pine DS, Hammen C, March JS, Plotsky PM, Weissman MM, Biederman J, Goldsmith HH, Kaufman J, Lewinsohn PM, Hellander M, Hoagwood K, Koretz DS, Nelson CA, Leckman JF. Development and natural history of mood disorders. Biological Psychiatry 2002; 52: 529-542. 7. Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin 2001; 127: 773-96. 8. Harrington R, Dubicka B. Natural history of mood disorders in children and adolescents. In: Goodyer I, editor, The depressed child and adolescent. 2 nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 353-381. 9. Harrington R. Affective disorders. In Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry. 4th Edition. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002. pp. 463-485. Depression 24 10. Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: Age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1994; 33: 809-818. 11. Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the "kindling" hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychological Review 2005; 112: 417-445. 12. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2000; 109: 504-511. 13. Segal Z, Williams J, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford; 2002. 14. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behaviour. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2001; 40(4): 495-9. 15. Carr A. Depression and attempted suicide in adolescence. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002. 16. NICE. Self-Harm. The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in Primary and Secondary care. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. 17. Eley, T. C., Sugden, K., Corsico, A., Gregory, A. M., Sham, P. & McGuffin, P. et al. (2004). Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Mol Psychiatry, 9, 908-915. 18. Hankin B, Abela J. Developmental psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. 19. Shortt A, Spence S. Risk and protective factors for depression in youth. Behaviour Change 2006; 23(1): 1-30. 20. Rice F, Harold GT, Thapar A. The genetic aetiology of childhood depression: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2002; 43: 65-80. Depression 25 21. Zubenko GS, Hughes HB III, Stiffler JS, Zubenko WN, Kaplan BB. Genome survey for susceptibility loci for recurrent, early-onset major depression: results at 10 cM resolution. American Journal of Medical Genetics (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2002; 114: 413-422. 22. Scourfield J, Rice F, Thapar A, Harold GT, Martin N, McGuffin P. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: Changing aetiological influences with development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2003; 44: 968-976. 23. Kendler K, Gatz G, Gardner C, Pederse N. Personality and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 2006; 63(10): 1113-1120. 24. Zalsman G, Oquendo M, Greenhill L, Goldberg P, Kamali M, Martin A, Mann J. Neurobiology of depression in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2006; 15(4): 843-868. 25. Goodyer I. Life events: Their nature and effects. In: Goodyer I, editor. The depressed child and adolescent. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 204-32. 26. Blatt S. Experiences of depression. Theoretical, clinical and research perspectives. Washington, DC: APA; 2004. 27. Coyne JC, Whiffen VE. Issues in personality as diathesis for depression: The case of sociotropy-dependency and autonomy-self-criticism. Psychological Bulletin 1995; 118: 358-378. 28. Garber J, Braafladt N, Weiss B. Affect regulation in depressed and nondepressed children and young adolescents. Development and Psychopathology 1995; 7: 93115. 29. Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, McCarty CA Control-related beliefs and depressive symptoms in clinic referred children and adolescents: Developmental differences and model specificity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2001; 110: 97109. Depression 26 30. Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly 1987; 1: 5-37. 31. Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review 1989; 96: 358-372. 32. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1991; 100: 569-582. 33. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Volume 3. Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1980 34. Hankin B. Adolescent depression: Description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy and Behaviour 2006; 8(1): 102-114. 35. Haggerty R, Sherrod L, Garmezy N, Rutter M. Stress, risk and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms and interventions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. 36. Luthar S. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. 37. Carr A. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Clinical Psychology. 2 nd Edition. London: Routledge; 2006. 38. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1998; 37: 63. 39. NICE. Depression in children and young people. identification and management in primary, community and secondary care. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2005. 40. Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Centre for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. 41. Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Depression 27 Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Centre for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. 42. Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2 nd Edition (BASC-2). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service Publishing; 2004 43. Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory. technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-health Systems; 2003. 44. Beck J, Beck AT, Jolly J, Steer R. Beck youth inventories. Second edition for children and adolescents (BYI-II). San Antonio: TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2005. 45. Reynolds W. Reynolds Child Depression Scale (RCDS). Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. 46. Reynolds, W. Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale, 2nd Edition (RADS-2). Professional Manual. Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2002. 47. Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 1995; 5: 237-249. 48. Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught A, Brown K, Spitznagel E. The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2004; 43: 708-717. 49. Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H. The Development and Well-being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2000; 41: 645-657. 50. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the Depression 28 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000; 39: 28-38. 51. Reich W. Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000; 39: 59-66. 52. Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000; 39: 3948. 53. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children: present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1997; 36: 980–988. 54. Ablow J, Measelle J. The Berkeley Puppet Interview. Berkeley CA, University of California at Berkeley; 1993. 55. Lucas CP, Fisher P, Luby J. Young-Child DISC-IV Research Draft: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. New York: Columbia University, Division of Child Psychiatry, Joy and William Ruane Centre to Identify and Treat Mood Disorders; 1998. 56. Egger HL, Angold A. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): a structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp 223-243. 57. Hazell P, O'Connell D, Heathcote D, Henry D. Tricyclic drugs for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002317. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002317; 2002 58. Hall W. How have the SSRI antidepressants affected suicide risk. Lancet 2006; 367: 1959-1962. 59. Healy D. Lines of evidence on the risks of suicide with selective serotonin reuptake Depression 29 inhibitors. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2003; 72: 71-79. 60. Gibbons R, Hur K, Bhaumik D, Mann, J. The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1898-1904. 61. Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 2006; 132: 132149. 62. Michael KD, Crowley SL. How effective are treatments for child and adolescent depression? A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 2002; 22: 247-269. 63. Harrington R, Whittaker J, Shoebridge P, Campbell F. Systematic review of efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies in childhood and adolescent depressive disorder. British Medical Journal 1998; 316 (7144): 1559-1563. 64. Lewinsohn P, Clarke G. Psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Clinical Psychology Review 1999; 19(3): 329-342. 65. Reinecke M, Ryan N, Dubois D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1998; 37(1): 26-34. 66. Weersing V, Brent D. Cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescent depression. In: Kazdin A, Weisz J, editors/ Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 135-147 67. Compton S, March J, Brent D, Albano A, Weersing V, Curry J. Cognitivebehavioural psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2004; 43: 930-959. 68. Clarke G, Debar L, Lewinsohn P. Cognitive behavioural group treatment for adolescent depression. In: Kazdin A, Weisz J, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. Depression 30 pp.120-134 69. Rohde P, Lewinsohn P, Clarke G, Hops H, Seeley J. The adolescent coping with depression course. A cognitive behaviour approach to the treatment of adolescent depression. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: empirically based strategies for clinical practice. 2 nd Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 219-237. 70. Weisz J, Southmam-Gerow M, Gordis E, Connor-Smith J. Primary and secondary control enhancement training for youth depression: Applying the deploymentfocused model of treatment development and testing. In: Kazdin A, Weisz J, editors, Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 165-186 71. Stallard P. Think good - feel good: A cognitive behaviour therapy workbook for children and young people. Chichester: Wiley; 2002. 72. Stallard P. A clinician’s guide to think good feel good: the use of CBT with children and young people. Chichester: Wiley; 2005. 73. Trowell R, Joffe I, Cmpbell J, Clemente C, Almqvist F, Soininen M, KoskenrantaAalto U, Weintraub S, Kolaitis G, Tomaras G, Anastasopolous D, Grayson K, Barnes J, Tsiantis J. Childhood depression: A place for psychotherapy: An outcome study comparing individual psychodynamic psychotherapy and family therapy. European and Adolescent Psychiatry. In press. 74. Muratori F, Picchi L, Bruni G, Patarnello M, Romagnoli G. A two-year follow-up of psychodynamic psychotherapy for internalizing disorders in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2003; 42: 331-339. 75. Malan D, Osimo F. Psychodynamics, training, and outcome in brief psychotherapy. London: Butterworth; 1992, 76. Davenloo H. Basic principles and techniques in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. New York: Spectrum. 1978. Depression 31 77. Byng-Hall J. Rewriting family scripts. Improvisation and change. New York: Guilford; 1995. 78. Will D, Wrate R. Integrated family therapy. London: Tavistock; 1985. 79. Cramer B, Palacio Espasa F. La Pratique des Psychotherapies Mères-Bébés. Paris: PUF; 1993. 80. Mufson L, Pollack Dorta K. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. In: Kazdin A, Weisz J, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 148-164 81. Mufson L., Pollack Dorta K, Moreau D, Weissman M. Efficacy to effectiveness: Adaptations of interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescent depression. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice. 2nd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 165-186. 82. Rossello J, Bernal G. New developments in cognitive behavioural and interpersonal treatments for depressed Puerto Rican adolescents. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice. 2nd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 187-218 83. Mufson L., Dorta Pollack K, Moreau D, Weissman M. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. 2nd edition. New York: Guilford; 2004 84. Diamond GS, Reis BF, Diamond GM, Siqueland L, Isaacs L. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: a treatment development study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2002; 41:1190-119. 85. Diamond G. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed and anxious adolescents. In: Lebow J, editor. Handbook of clinical family therapy. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 17-41. 86. Sanford M, Boyle M, McCleary L, Miller J, Steele M, Duku E, Offord D. A pilot study Depression 32 of adjunctive family psychoeducation in adolescent major depression: Feasibility and treatment effect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2006; 45(4): 86-395. 87. Falloon I, Boyd J, McGill C. Family care of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford; 1984 88. Curry J, Wells K, Lochman J, Craighead W, Nagy P. Cognitive-behavioural intervention for depressed, substance-abusing adolescents: development and pilot testing. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2003; 42(6); 656-65. 89. Robin A, Foster S. Negotiating parent adolescent conflict. New York: Guilford; 1989. 90. Huey S, Henggeler S, Rowland M, Halliday-Boykins C, Cunningham P, Edwards J. Multisystemic therapy reduces attempted suicide in a high-risk sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2004; 43: 183-190. 91. Henggeler S, Schoenwald S, Rowland M, Cunningham P. Serious emotional disturbance in children and adolescents. multisystemic therapy. New York: Guilford; 2002. 92. Cheung A, Emslie G, Mayes T. Review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in youth depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2005, 46(7), 735754. 93. Vasa R, Carlino A, Pine D. Pharmacotherapy of depressed children and adolescents: current issues and potential directions. Biological Psychiatry 2006; 59(11): 1021-1028. 94. TADS team. Fluoxetine, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, and Their Combination for Adolescents With Depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 2004; 292(7): 807-820. 95. Curry, J. Rohde, P., Simons, A., Silva, S., Vitello, B. (2006) Predictors and Depression 33 moderators of acute outcome in the treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2006; 45 (12): 1427-1439. 96. Goodyer I, Dubicka B, Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Byford S, Breen, S, Ford, C, Barrett, B, Leech, A, Rothwell, J, White, L, Harrington, R. Adolescent Depression Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). A Randomised Controlled Trial of SSRIs with and without cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression. British Medical Journal In press. 97. Clarke G. Debar L, Lync, F, Powell J, Gale J, O’Connor E, Ludman E, Bush T, Lin E, vonKorff M, Herbert S. A randomized effectiveness trial of brief cognitivebehaviour therapy for depressed adolescents receiving antidepressant medication. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2005; 44: 888-98. 98. Melvin G, Tonge B, King N, Heyne D, Gordon M, Ester K. A Comparison of CognitiveBehavioural Therapy, Sertraline, and Their Combination for Adolescent Depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2006; 45: 1151-1161. 99. Walter G, Rey JM, Mitchell PB. Electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1999; 40: 325-34. 100. Scott A. The ECT handbook. 2nd edition. The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists special committee on ECT. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005. 101. NICE. Guidance on the use of electroconvulsive therapy. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. 102. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for use of electroconvulsive therapy with adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2004; 43 (12): 1521-1539. Depression __________________ 34 Depression 35 Table 1. Criteria for a major depressive episode DSM IV TR ICD 10 A. Five or more of the following symptoms have been present during the same two week period nearly every day and represents a change from pervious functioning; at least one of the symptoms is ether (1) depressed mood or (2) Loss of interest or pleasure. Symptoms may be reported or observed. In a typical depressive episode the individual usually suffers from depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment and reduced energy leading to increased fatigueability and diminished activity. Marked tiredness after only slight effort is common. Other common symptoms are: a. reduced concentration and attention b. reduced self-esteem and confidence c. ideas of guilt and unworthiness d. bleak and pessimistic views of the future e. ideas or acts of self harm or suicide f. disturbed sleep g. diminished appetite. 1. Depressed mood. In children and adolescents can be irritable mood. 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in almost all daily activities. 3. Significant weight loss or gain (of 5% per month) or decrease or increase in appetite. In children failure to make expected weight gains. The lowered mood varies little from day to day and is often unresponsive to circumstances and may show a characteristic diurnal variation as the day goes on. 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia. 5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation. 6. Fatigue or loss of energy. 7. Feelings of worthlessness, excessive guilt. 8. Poor concentration and indecisiveness 9. Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. B. Symptoms do not meet criteria for mixed episode of mania and depression. C. Symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social occupational, educational or other important areas of functioning D. Symptoms not due to the direct effects of a drug or a general medical conditions such as hypothyroidism. E. The symptoms are not better accounted for by uncomplicated bereavement. Some of the above symptoms may be marked and develop characteristic features that are widely regarded as having special significance for example the somatic symptoms which are: loss of interest or pleasure in activities that are normally enjoyable; lack of emotional reactivity to normally pleasurable surroundings; waking in the morning 2 hours or more before the usual time; depression worse in the mornings; psychomotor retardation or agitation; marked loss of appetite or weight; marked loss of libido. Usually the somatic syndrome is not regarded as present unless at least four of these symptoms are present. Atypical presentations are particularly common in adolescence. In some cases anxiety, distress, and motor agitation may be more prominent at times than depression and mood changes may be masked by such features as irritability, excessive consumption of alcohol, histrionic behaviour and exacerbation of pre-existing phobic or obsessional symptoms or by Hypochondriacal preoccupations. A duration of two weeks is required for a diagnosis. Note: Adapted from DSM IV TR (APA, 2000), ICD 10 (WH0, 1992).