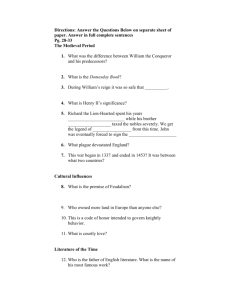

Chapter 2

advertisement

Chapter 2 Troilus and Criseyde Troilus and Criseyde is Geoffrey Chaucer's poem in rhyme royal re-telling the tragic love story of Troilus, a Trojan prince, and Criseyde. Cressida is a character who appears in many Medieval and Renaissance retellings of the story of the Trojan War. She is a Greek woman, captured and enslaved by the Trojans, who falls in love with a Trojan prince, Troilus. She pledges everlasting love, but when she is sent back to the Greeks as part of a hostage exchange, she goes to live in the Greek warrior Diomedes' tent. She was usually depicted by writers as a paragon of female inconstancy. Many Chaucer scholars regard this as his best work, even including the better known but incomplete Canterbury Tales. The comparisons are not really fair as they are very different styles: Troilus and Criseyde is a single, coherent story, whereas The Canterbury Tales is a story cycle containing many different sections with different styles representing a range of narrators. It can be argued that Troilus and Criseyde is an example of a courtly romance, and although it does contain many common features of the genre, generic classification is an area of significant debate in most Middle English literature. Although mentioned in Homer the story of Troilus and Criseyde was first written by Benoît de Sainte-Maure in his poem, Roman de Troie, Boccaccio re-wrote the story in his Il Filostrato which in turn was Chaucer's main source. The poem was continued by Robert Henryson in his Testament of Cresseid. Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida was based in part on Chaucer's poem. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late 14th century metrical romance recorded in a manuscript containing three other pieces of an altogether more Christian orientation, which are linked by a commonality of dialect usage. The dialect is the North-West Midland form of Middle English. The core of the story, however, is far older and embraces many elements, the most prominent being the severed head theme, central to Celtic mythology, although it is also coloured by events of the time, chief amongst which were the Black Death. The manuscript, Cotton Nero A.x is in the British Museum. The first modern edition was published by J. R. R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon in 1925. 1 Contents [hide] 1 The poet 2 The verse form 3 The language 4 Plot synopsis o 4.1 The Challenge o 4.2 Sir Gawain's Journey o 4.3 The Lord's Bargain o 4.4 The Meeting with the Green Knight 5 References o 5.1 Editions o 5.2 Translations o 5.3 Commentary and criticism 6 External links The poet The three other pieces found with Gawain, although untitled in their longhand exposition, have come to be known as Pearl, Patience, and Cleanness (alternately Purity). It is understood that the Cotton manuscript is in the hand of the copyist and not the author. There is thus nothing explicit that says all four poems in the manuscript are by the same poet. However, from a comparative analysis of dialect, verse form and diction, it has become generally accepted that each of the four poems does in fact have the same authorship. We of course do not know the name of this poet, but just from an informed reading of his works, we still know a little bit about the man. Tolkien, in the introduction to his posthumous translation, writes He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery. 2 The manuscript has been dated to the round year of 1400, and it is believed that the poet flourished some short time before that; he was thus a contemporary of Chaucer, although remote from him in almost every other way. Before the manuscript came into the possession of Robert Cotton, it had found a place in the library of Henry Savile of Bank in Yorkshire, who lived from 1568 - 1617. Nothing is known of it, or its author, before that. Although there is less unanimity, the Gawain-poet may have also written the alliterative poem St. Erkenwald, believed to have been composed in 1386. The verse form Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is written in the style of what linguists would later refer to as the Alliterative Revival of the fourteenth century. Instead of focusing on a metrical syllabic count and rhyme, the alliterative form relied on the agreement of (usually a pair of) stressed syllables at the beginning of the line with (usually) a third and fourth at the end of the line. The line always finds a "breath-point" at some point after the first two stresses, dividing the line into two half-lines, separated by a caesura. Although the Gawain-poet was a bit freer with convention than poets of greater antiquity, this more or less had been the form of alliterative poetry going back into the Old English. The Gawain-poet, however, did embellish the form with some end-rhyme, as it happens. His structure has come to be known as the bob and wheel. The poet broke his alliterative lines into variable-length groups and ended these nominal stanzas with four three-beat lines rhyming abab (the wheel) and a one-beat tag that rhymes a (the bob). These lines also alliterate. The language As has been noted, the poem is written in the North-West Midlands dialect of Middle English, and that dialect must be considered as something of a dead tributary to the course of history that the English language would take. As a result, the untranslated poem is only dimly intelligible to those who have not studied Middle English. As Tolkien tells us, "[i]ndeed in their own time the adjectives 'dark' and 'hard' would probably have been applied to these poems by most people who enjoyed the works of Chaucer." Here are the first four lines of the poem in its untranslated form: Siþen þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at Troye, þe borȝ brittened and brent to brondez and askez, 3 þe tulk þat þe trammes of tresoun þer wrotȝ, Watz tried for his tricherie, þe trewest on erthe; Spoiler warning: Plot and/or ending details follow. In the story, Gawain, a knight of King Arthur in Camelot, becomes a guest at Hautdesert Castle. During this sojourn, three hunts take place, and are paralleled by three temptations laid before Gawain by the Green Knight's wife. Plot synopsis The Challenge The story, set in verse, begins at King Arthur's court at Camelot on New Year's day. As Arthur's court is feasting, a stranger, the gigantic Green Knight, on horseback and armed with an axe, enters the hall and lays down a challenge. One of Arthur's knights may take the axe and strike a single blow against the Green Knight, on the condition that the Green Knight, if he survives, will return the blow one year and one day later. Sir Gawain, the youngest of Arthur's knights, accepts the challenge and chops off the giant's head. The Green Knight, still alive, picks up his own head, reminds Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel in a year and a day, and rides off. [edit] Sir Gawain's Journey Almost a year later, on All Hallows Day, Sir Gawain sets off in his finest armour, on his horse Gringalet, to find the Green Chapel and complete his bargain with the Green Knight. His shield is marked with the pentangle, a symbol of Biblical origin, which is to remind him of his knightly obligations. The journey takes him from the isle of Anglesey to a castle somewhere in the West Midlands. Gawain meets the lord of the castle and his beautiful wife, who tell him that the Green Chapel is close by, and suggest that he stay with them. [edit] The Lord's Bargain The lord, before setting off on a day's hunting, offers a deal to Sir Gawain. The lord will give Gawain whatever he catches, on condition that Gawain gives to the lord, without explanation, whatever he might gain during the day. Gawain accepts. That night, while the lord is still away, the lady of the castle visits Gawain's room and tries 4 to seduce him, claiming that she knows of the reputation of Arthur's knights as great lovers. Gawain, however, keeps to his promise to remain chaste until his mission to the Green Chapel is complete, and yields nothing but a single kiss. When the lord returns with the deer he has killed, he hands it straight to Sir Gawain, as agreed, and Gawain responds by returning the lady's kiss to the lord. According to the lord's bargain, Gawain refuses to explain where he won the kiss. On his second night, Gawain again receives a visit from the lady, and again politely refuses her advances. Next day, when the lord returns, there is a similar exchange of a hunted boar for two kisses. On his third night, when the lady visits his chamber, Gawain maintains his chastity but accepts a silk girdle, which is supposed to keep him from harm, as a parting gift. The next day, the lord returns with a fox, which he exchanges with Gawain for three kisses. However, Gawain keeps the girdle from the lord so that he can use it in his forthcoming encounter with the Green Knight. The Meeting with the Green Knight The next day, Gawain leaves for the Green Chapel, with the lady's silk girdle hidden under his armour, and accompanied by a guide from the lord's castle. Leaving the guide, who is afraid to approach the Green Chapel, Gawain finds the Green Knight busy whetting the blade of an axe in readiness for the fight. As arranged, the Green Knight attempts to behead Gawain, but after three attempts Gawain remains only slightly injured, the third blow barely cutting his neck. The Green Knight then reveals himself to be an alter ego of the lord of the castle, Bertilak de Hautdesert, and explains that the three axe blows were for the three occasions when Gawain was visited by the lady. The third blow, which drew blood, was a punishment for Gawain's acceptance of the silk girdle. The Green Knight explains that Gawain's trial was arranged by Morgan le Fay, mistress of the wizard Merlin and now a guest at Hautdesert castle. The two men part on cordial terms, Gawain returning to Camelot. There, Sir Gawain recounts his adventure to Arthur and explains his shame at having partially succumbed to the lady's attempts, if only in his mind. Arthur refuses to blame Gawain and decrees that all his knights should henceforth wear a green sash in recognition of Gawain's courage and honour. 5 Thomas Malory Sir Thomas Malory (c.1405–March 14, 1471) was the author or compiler of Le Morte d'Arthur. The antiquary John Leland believed him to be Welsh, but most modern scholarship and this article assumes that he was Sir Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel in Warwickshire. The surname appears in various spellings, including Maillorie and Maleore. The name comes from the Old French adjective maleüré (from Latin male auguratus) meaning ill-omened or unfortunate. Few facts are certain in Malory's history. From his own words he is known to have been a knight and prisoner, and his description of himself as "a servant of Jesu both day and night" has led to the inference that he might have been a priest. It is believed that he was knighted in 1442 and entered the British Parliament representing Warwickshire in 1445. In 1450, it appears that he turned towards a life of crime, being accused of murder, robbery, stealing, poaching, and rape. However, the validity of these charges are the subject of much controversy given Malory's unclear political affiliations. False charges were common amidst the political strife of the War of the Roses. Supposedly while imprisoned for most of the 1450s (mostly in London's Newgate Prison), he began writing an Arthurian legend that he called The Book of King Arthur and His Noble Knights of the Round Table. Little else is known of Malory's life, but he is believed to have been a Lancastrian during the Wars of the Roses, or perhaps a retainer of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick who openly defected to the Lancastrian camp from that of the Yorkists in 1469. His work was first published posthumously by William Caxton as Le Morte d'Arthur in 1485. Malory is believed to have obtained the material for his work from many French sources in addition to earlier English Arthurian Romances, most notably the stanzaic Morte Arthur and the alliterative Morte Arthure. In the preface to the first edition of the Le Morte D'Arthur, William Caxton speaks of the work as printed by himself "after a copy unto me delivered, which copy Sir Thomas Malory did take out of certain books of French, and reduced it into English." Malory himself tells us that he finished the book in the ninth year of King Edward IV of England (about 1470). Le Morte D'Arthur brought together the various strands of the legend in a prose romance which many critics reckon the best of its kind. Some claim it to have the status of "the first recognisable novel", although this claim is disputed. Le Morte D'Arthur was used by T.H. White as the basis for his work The Once and Future King, and as such, included a cameo appearance of Malory near the end – as a young boy, he is knighted by Arthur, who orders him to come home and spread the 6 stories and ideals of Camelot to all who will listen. His cameo appearance was included in the Broadway musical Camelot, which was based on White's book. Le Morte D'Arthur was also the substantial basis for John Boorman's 1981 movie, Excalibur, including in it all the elements of the book. Le Morte d'Arthur Le Morte d'Arthur (The Death of Arthur)—the title is actually spelled as Le Morte Darthur in the first printing and also in some modern editions—is Sir Thomas Malory's compilation of some French and English Arthurian romances. It was first published in 1485 by William Caxton. Le Morte d'Arthur has become the base story of many modern Arthurian stories, including T. H. White's The Once and Future King. Contents [hide] 1 About the text 2 Selected bibliography and external links o 2.1 The work itself o 2.2 Commentary About the text Malory likely started work on it while he was in prison in the early 1450s and completed it by 1470. William Caxton may have named it Le Morte Darthur instead of Malory's original title: The hoole booke of kyng Arthur & of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table. Many modern editions update the spelling and some of the pronouns from Malory's original Middle English, repunctuate and reparagraph, but otherwise leave the text as it was written. Spoiler warning: Plot and/or ending details follow. Caxton was also responsible for separating it into 21 books comprised of 507 chapters for easier reading. Yet it is apparent that Malory intended the work to be divided principally into eight tales: 1. The birth and rise of Arthur 7 2. King Arthur's war against the Romans 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Launcelot Gareth (brother of Gawain) Tristram and Isolde The Quest of the Holy Grail The affair between Launcelot and Guinevere The breaking of the Knights of the Round Table and the death of Arthur Most of the events in the book take place in Britain and France in the latter half of the 5th century. In some parts it ventures farther afield, to Rome and to Sarras (near Babylon), and recalls Biblical tales from the ancient Middle East. All editions prior to 1934 were based on the edition printed by Caxton. However, in 1934, when the library of Winchester College was being catalogued, a previously unknown manuscript copy was discovered—one of the most important new medieval manuscripts discovered in the twentieth century. The Winchester manuscript is regarded as being mostly but not always closer to Malory's original than is Caxton's text, although both derive separately from an earlier copy. Curiously, microscopic examination of ink smudges on the Winchester manuscript showed the marks to be offsets of newly printed pages set in Caxton's own font indicating that same manuscript had been in Caxton's print shop. But Caxton used some other manuscript for his base text. Unlike the Caxton edition, the Winchester MS is not divided into books and chapters and indeed, in his preface, Caxton takes credit for the division. Eugène Vinaver in his edition to the Winchester Manuscript urged strongly that Malory had in fact not written a single book, but had produced a series of intentionally independent Arthurian tales that were not necessarily intended to cohere with one another, whence Vinaver called his edition The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. This theory explained discrepancies between the different sections which had bothered commentators. But opposition critics pointed out that discrepancies still existed within the tales that Vinaver claimed were independent works and that Malory, particularly in his later tales, added links to his own versions of events in earlier tales, especially in the last two tales. That showed that Malory felt that the tales should cohere, even if Malory did not get to the point of producing a revision that achieved that goal. Even Vinaver treated the last two of his tales as intended to be read together. The discussion tended to get bogged down into debate on the meaning of unity and what book should be along with accusations that Vinaver's own divisions in his edition ignored the divisions actually indicated in the manuscript. In fact, readers of Malory do mostly continue to read what Malory wrote as a single work comprising several tales and tales within those tales, and which also contains a number of 8 contradictions between different parts of this supposed whole work which are balanced or surpassed by the links between different parts of this supposed whole work. Mystery play Mystery plays or miracle plays are one of the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. They developed from the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song, such as the Quem Quaeritis - a short musical performance set at the tomb of the risen Christ. These simple structures were developed with tropes, verbal embellishment of the liturgical text, and became more elaborate. As these liturgical plays became more popular, more vernacular elements were introduced and non-clergy began to participate. As the dramas became increasingly secular, they began to be performed entirely in the vernacular and were moved out of the churches by the 13th or 14th century. These vernacular religious performances were taken over by the guilds, with each guild taking responsibility for a particular piece of scriptural history. From the guild control they gained the name mystery play or just mysteries, from the Latin mysterium (meaning handicraft and relating to the guilds). Mystery plays should not be confused with Miracle plays, which specifically re-enacted episodes from the lives of the saints. Also, Miracle plays were performed in Latin, unlike Mysteries which were meant to be understood by the common man. The mystery play developed into a series of plays dealing with all the major events in the Christian calendar, from the Creation to the Day of Judgment. By the end of the 15th century, the tradition of acting these plays in cycles on festival days (such as the Feast of Corpus Christi) was established across Europe, each play was performed on decorated carts called pageants, that moved about the city to allow different crowds to watch each play. The entire cycle could take up to twenty hours to perform and could be spread over a number of days. Taken as a whole, these are referred to as Corpus Christi cycles. The plays were performed by amateurs and used the stanza form that was already well known; they were often marked by the extravagance of the sets and 'special effects'. English mystery plays There are four complete or nearly complete extant English cycles: the York cycle of forty-eight pageants; the Towneley cycle of thirty-two pageants, acted at Wakefield; 9 the N Town cycle of forty-three pageants (also called the Ludus Coventriae cycle or Hegge cycle) acted probably in Lincolnshire or Norfolk, and the Chester cycle of twenty-four pageants. Also extant are two pageants from a New Testament cycle acted at Coventry and one pageant each from Norwich and Newcastle-on-Tyne. There are three surviving plays in Cornish, and several cyclical plays survive from continental Europe. The cycles differed widely in content. Most contain episodes such as the Fall of Lucifer, the Creation and Fall of Man, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Flood, Abraham and Isaac, the Nativity, the Raising of Lazarus, the Passion, and the Resurrection. Other pageants included the story of Moses, the Procession of the Prophets, Christ's Baptism, the Temptation in the Wilderness, and the Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin. In given cycles, the plays came to be sponsored by the newly emerging Medieval craft guilds. The York mercers, for example, sponsored the Doomsday pageant. Perhaps the most famous of the mystery plays were those of Wakefield. These are attributed to the Wakefield Master, an anonymous playwright who wrote in the fifteenth century. Early scholars suggested that a man by the name of Gilbert Pilkington was the author, but this idea has been disproved by Craig and others. The epithet "Wakefield Master" was first applied to this individual by the literary historian Gayley. The Wakefield Master gets his name from the geographic location where he lived, the market-town of Wakefield in Yorkshire. He may have been a highly educated cleric there, or possibly a friar from a nearby monastery at Woodkirk, four miles north of Wakefield. This anonymous author wrote a series of 32 plays (each averaging about 384 lines) called the Towneley Cycle. A cycle is a series of mystery plays performed during the Corpus Christi festival. These works appear in a single manuscript, which was kept for a number of years in Towneley Hall of the Towneley family. Thus the plays are called the Towneley Cycle. The manuscript is currently found in the Huntington Library of California. It shows signs of Protestant editing--references to the Pope and the sacraments are crossed out, for instance. Likewise, twelve manuscript leaves were ripped out between the two final plays because of Catholic references. This evidence strongly suggests the play was still being read and performed as late as 1520, perhaps as late in Renaissance as the final years of King Henry VIII's reign. This fact says something about the power and influence of the medieval mystery play--the genre was still popular when Shakespeare was a small boy, and he might very well have grown up watching such plays before writing his own. The best known pageant in the Wakefield cycle is The Second Shepherds' Pageant, a burlesque of the Nativity featuring Mak the sheep stealer and his wife Gill, which 10 more or less explicitly compares a stolen lamb to the Saviour of mankind. The Harrowing of Hell, derived from the apocryphal Acts of Pilate, was a popular part of the York and Wakefield cycles. The dramas of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods were developed out of mystery plays. The Mystery Plays were revived in York in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain. Morality play Morality plays (15th-16th c.): a type of theatrical allegory where the characters, in the form of personified moral attributes, must validate the virtues of Godly life by prompting the protagonist to choose such life over evil. These plays, most popular in 15th and 16th century Europe, helped move European theater from being religiously based to secularly based. However, the plays still offered moral instruction and together with mystery plays and miracle plays constituted the theater of the Middle Ages. Examples of morality plays include the French Condemnation des banquets by Nicolas de Chesnaye and the English The Castle of Perseverance and Everyman, which is today considered the best of the morality plays. Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality_play" Everyman From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Everyman (c. 1509-19) is a morality play. Everyman is derived from a 921 line long Flemish play called Elckerlijc written by Peter van Diest in the second half of the 15th century. It was widely translated, and the English translation became Everyman, which is now world famous. Everyman, an allegorical figure of the human race, is summoned by the allegorical figure of death. He discovers that his friends Fellowship, Kindred, Cousin, and Goods will not go with him. It is Good Deeds (or Virtue), whom he previously neglected, who finally supports him and who offers to justify him before the throne of God. Lines from this play provided the inspiration for the name of the popular literature series Everyman's Library. Another well-known version of the play is Jedermann by the Austrian playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal, which has been performed annually at the Salzburg Festival since 1920. 11 In literature and drama, the term "everyman" has come to mean an ordinary individual, with whom the audience or reader is supposed to be able to identify, and who is often placed in extraordinary circumstances. Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Everyman" 12