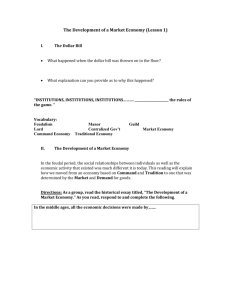

MODULE 3: - The Ohio State University

advertisement