Porush - New Media Consortium

advertisement

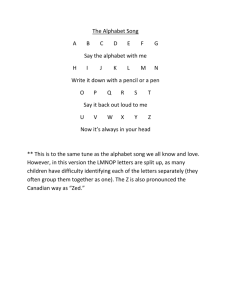

TELEPRESENCE AND TELEPATHY: ABC2VR David Porush, Co-founder and chairman SpongeFish david@spongefish.com [1] "He went to the window [of his hotel room in Istanbul]...There was another hotel across the street. It was still raining. A few letterwriters had taken refuge in doorways, their old voiceprinters wrapped in sheets of clear plastic, evidence that the written word still enjoyed a certain prestige here. It was a sluggish country." - William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984) Like many New Worlds not yet invented nor yet colonized, the Web is territory contested by all sorts of partisans, even on the boatride over. There we shall achieve new freedoms. There we shall create new societies founded on the principles of true human nature – generous, slavish, rational, materialistic. There we will correct all the ills our old social order bred. As we speak, the web is rapidly re-negotiating and reorganizing the relations among minds, selves, others. Some writers have even supposed that virtual reality, of which the Web is a primitive instance, will deliver new transcendental forms. Of all aspects of the future Web, the questions surrounding education on the Web receive the most vociferous debate, especially in academia and among academics, naturally enough. The Web presents a new place for us to get it right, and everyone has their own idea of “right.” Some even believe it is intrinsically wrong for us to use the Web for education. It supplants traditional warm-body classroom teaching and lecturing with means for automation of pedagogy, control, invasion of privacy, and deindividualization. Not least, the Web seems to ally naturally with commercial interests, which can corrupt and bend education to its mercenary goals. 1 E. Wayne Ross, “The Promise and Perils of E-Learning: A critical look at the new technology” http://www.zmag.org/ZMag/articles/dec00ross.htm 1 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush The SUNY Learning Network currently serves 100,000 students on 40 campuses of the State University of New York. SUNY is the U.S.’s largest comprehensive public university, with 64 campuses including research universities, four-year colleges, community colleges and technical colleges. It’s the happy job of my office, which is responsible for the SUNY Learning Network and other missions in academic technology, to identify, develop and deploy the best technologies that will broaden and enrich the core values and ideals of academia. This includes everything from the expansion of educational opportunities to a wider population of students to determining what sorts of pedagogies we should encourage in the online classroom. Given the complexity, sheer size, and diversity of the interests my office serves, it would be tempting to simply let a Darwinian environment thrive: provide resources, enforce some rules of engagement (e.g. policies for how to grant credit online) and let the games begin, and wait to see what creatures emerge from that jungle. However, ideologies among us academics make demands on the shape of online learning and. On one end of the spectrum, there is a strong trend in the U.S. to pin learning to measurable, specifiable outcomes, a trend that shows up in K-12 education as legislated demands on outcomes to be produced by schools in the performance of their students in standardized testing. On the other end of the spectrum, there is a strong bias from within academia itself, especially in Schools of Education theory, towards a constructivist perspective. This bias often manifests itself as a call for the professor to give up his or her authority in favor of “learner-centrism” or the encouragement of self-guided communities of learners. Similarly, some administrators want online learning to create efficiencies, so that fewer faculty can teach more students. Other theorists suggest that asynchronous discussion postings should be the site of knowledge construction, while and dress up a strong aversion to testing of any sort in the guise of best practices. The contest for the New World to be dominated by this or that fundamentalism or ideology or untested theory of pedagogy is expensive and distracting, especially if they end up narrowing and parochializing or balkanizing the range of learning that could occur with a little shared vision and coordination. Rather, in our planning for how learning will unfold in this medium, we should try to plot the trajectory of this medium against the arcs traced by other media. This tack should enable us to husband our public resources more responsibly and to provide a more viable, robust learning environment technology to serve a wider range of learning. Chuck Dzuiban at the University of Central Florida has recently noted that as we track the generations in their differential responses to online learning, the youngest cadres of students (The Next Gen vs. the X-Gen or Baby Boomers) are less satisfied by the technology environment we provide them, even though they seem to have more success learning on it. 2 In other words, the technology we old technocrats and e-learning professors are designing for them is boring them, even though they handle it with ease. 2 Dzubian, Ch., D., Hartman, J. L., Moskal, P. D. (2004). “Blended Learning,” EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research. EDUCAUSE Research Bulletin. Vol. 2004, # 7, March 30. David Porush Bla blah in here transition What can we learn from new communications technologies and how they’ve shaped culture and cognition through the centuries that humans have been inventing them? This chapter will look at one lesson in particular that we can extrapolate from the history of the media. Many modern electronic media seemed to promise a total transformation of society when they were new. Radio and television in their early days were surrounded by liberationist, redemptive, utopian, political and even transcendental claims.3 Early cultural optimists predicted how those media were going to alter and heal how we work, play, live, communicate, and most poignantly, teach and learn. Yet, like its predecessors, the Web has almost completed its transformation into yet another – if extraordinarily global, instantaneous, and intimate – mall. The Web has fulfilled one of its destinies through eBay and Amazon.com: it has become the world’s bazaar, bordered by the world’s largest bordello. What began as a way to swap files of text and data has evolved into the most remarkable arena for commerce. Through the development of increasingly flexible ways to share sensory experiences (light, sound, motion) and money (PayPal, e-commerce security) the Web has become extraordinarily efficient for identifying and exciting individualized desires and then delivering the consumer to the very product that will gratify that desire almost instantaneously, taking secure payment along the way. It itches, it scratches. It is also, like the best of bazaars, a great place to roam, seeking or being surprised by new sensations, knowledge, and experiences. But the web hasn’t been co-opted for commerce completely. Communications technologies do promote revolutions in cognition and culture, as history has shown and this chapter will explore. The bazaar will lure us out of the classroom every time. In some places and eras, progress will slip, as governments suppress or societies fail. But the ends for which we deploy different media proliferate and co-exist in parallel, and not necessarily to the exclusion of each other. At the same time, media tend to be almost infinitely expansible.4 And those twin lessons are good to remember when we watch how our students and children thrive on the Web: they’re googling for a paper reference, chatting online, downloading a video, playing a song, burning a disc, composing a document, managing multiple identities on AIM, playing a hand of Texas Hold ‘Em at a table in a virtual casino. 3 Technological Visions: The Hopes and Fears that Shape New Technologies edited by Sturken, Marita, Douglas Thomas and Sandra Ball-Rokeach (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003). See especially Marita Sturken and Douglas Thomas, “Technological Visions and the Rhetoric of the New.” This volume is both critique and expression of the phenomenon it critiques: inscribing a world not yet fully invented with ideologies produces utopian claims and partisan rhetoric. We should also note the extensive similarities between the evolutionary path of radio and the Web. As Thomas White notes on his website “The Early History of Radio – Pioneering Amateurs,” (http://earlyradiohistory.us/sec012.htm): “Radio captured the imagination of thousands of ordinary persons who wanted to experiment with this amazing new technology. Until late 1912 there was no licencing or regulation of radio transmitters in the United States, so amateurs -- known informally as "hams" -- were free to set up stations wherever they wished.” This was followed by licensing, restriction, the growth of large commercial networks, Even when the channel of transmission is physically limited – like those that depend on segments of the electromagnetic spectrum like radio – technology finds a way to parse and crowd and micro-segment the channel to produce more bandwidth, much as cities eventually find a way to build skyscrapers, beginning with the ziggurats of Babylon and Sumeria. 4 Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 3 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush The phonetic alphabet superceded but did not displace the communications devices that preceded it and which gave it birth, illustrating the principle that Older media persist and continue to live side by side. Oral cultures (rap), painting, pictograms, syllabic scripts, radio, television and telephone continue to survive robustly, within and around each other. Phylogenetically, back when the brain was simple, its expressive function was almost non-existent. There was a neat Kantian fit between animal and environment: The rules of the world out there, its physics, were not challenged by the rules of the world in here; there was a nice match. But then through some urgency that it is just as easy to talk about metaphysically or teleologically as in terms of some deterministic chaotic evolution, the brain exploded, human-like hominids started walking upright about 35,000 years ago, looking forward, using tools, colonizing the world, creating new social structures. The brain, like some imperial culture exploding off a remote island, started projecting itself onto the world, terraforming the Earth in its own image and leaving in its wake a trail of non-bio-degradable tools and waste. The brain also started talking, depicting, enacting versions of its experience in cave paintings, ritual dances, gestures, and a grammar of grunts. It became self-conscious. It recognized a mismatch between the world out there and the world in here: Hey! The world persists; we die! Self-consciousness and the idea of death were born in one fatal stroke and we acted self-consciously to shape our environment to forestall that inevitability. We organized and communicated to live. This powerful cybernetic loop among environment, culture, and brain that we recognize as uniquely human was initiated sometime between 35,000 and 10,000 years ago as a result of who-knows-whichbutterfly flapping who-knows-what sort of wings. Frances Hellige describes the growth of this feedback loop initiated by the development of language as a "snowball effect": a cycle of ever-widening gyres that eventually co-creates everything between the poles of culture and the biology of the brain itself, including demonstrable changes in structure and size of different regions of the brain. 5 In cybernetic terms, we call this a positive feedback loop. The brain sends information out into the environment, which feed newly intensified signals back into the brain system to destabilize the system anew, which in turn re-amplifies its message, like an over-sensitive microphone, and again re-broadcasts the message back onto the world. The universe screeches with the noise of the human brain fed back through it, a cyborg rock concert broadcast from our noisy Earth. Neurophysiologists and cognitive scientists who study the alphabet note that its effects on the brain can even be seen in the lifetime development of individual people. 6 Evidence is emerging that the use of language in the world helps reshape the brain from womb to tomb. A whole new discipline of neural plasticity has emerged in the last two decades, showing that the brain is not the static, geneticallydetermined machine we once thought it to be. It's happening to us, today, right now. Studies of aphasics and dyslexics with brain injuries show that the brain changes physiologically and progressively after the Joseph B. Hellige, Hemispheric Asymmetry: What's Right and What's Left, Harvard University Press, 1993. 5 6 See Charles Lumsden, Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origins of Mind David Porush injury, forging new connections, finding pathways around damages areas to accommodate functions. In other words, the brain under assault or given the prop to extend its activity will reorganize itself at the level of neural connections, even growing new ones. In all, it suggests that reading grows parts of the brain even in the lifetime of individual humans, just as losing the ability to read devolves the brain of individual humans, or forces the brain to re-wire itself. Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny: the cognitive abilities we grow up in our contemporary mediasphere trace the same line as the evolution of culture in its use of successively more complex, sensory, and intimate communications. Fun with your new brain: a brief history of the rise of the alphabet In transit, trying a new alphabet must have been (and still is) tantamount to an ongoing progressive hallucination. It lets you think things that you couldn't have thought before, makes connections for which your brain wasn't wired before, and invites you into different information processing patterns, different mental events or experiences. It's like having a whole new brain, or at least, the same operating system brain with new applications that transform the operating system. Now imagine the mass hallucination of an entire culture learning how to use writing for the first time, and then later, progressively more efficient scripts for the first time. Whole tribes of people, or important segments of them, put on this new cybernetic headgear virtually all at once. We can imagine this mass cybernetic experiment would be accompanied by social, epistemological, and metaphysical revolutions, apocalyptic prophesies, and re-definitions of the self in relation to body, mind, others, and the invisible. In short, it might provoke the emergence of a new religion. With this hypothesis, let’s take a look at the advent of writing itself. Imagine a time-lapse video of the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia before and just after the very first invention of writing, Sumerian pictographs in the late fourth millenium B.C. These time-lapsed films would show millions of years of animal activity, including the hunting gathering and some low-level animal husbandry (shepherding, desultory breeding) by upright hominids after 35,000 BC. As we approach 10,000 BC, activity begins to pick up pace and organization. Clusters of hominids show tool use, primitive mound building, expressive cave painting, and cultivation of the earth, though in indifferent and almost-random-seeming patterns, pockets that flare and fade. Then around 3800 BCE, Something leaps into a new order of rapid selforganization. Compressed into a few frames you see a dramatic transformation; blink and you'll miss the instant. These fertile regions undergo massive terraforming along rectilinear plots. Rivers are diverted into rectangular irrigation systems. Cities emerge, themselves rectilinear, or at least rectangles pressing against circles, deforming them into ovals, the ovals containing rectangles. Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 5 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush Zoom in with me now into the squared walls of the cities, and into the very rooms of the city, and we will find the intimate source of this sudden change. There, a row of hard stone benches, arranged regularly. It is a schoolroom for scribes! Hundreds of boys, mostly the sons of privileged nobility, sit for hours hunched over clay tablets, learning to scrawl in regular lines. Indeed, if we superimpose the scratching of David Porush these lines they look like the lines of irrigation written on the face of the earth itself, as seen from an orbiting satellite, both canals in the clay. Cuneiform Tablet from Ur – Courtesy of the British Museum www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/...cuneiform.html The discipline of the schoolchildren being tutored in script "canalizes" their thought processes, reinforcing certain pathways. It is hard not to imagine that what's written on neural habits and gets projected onto the world, which is literally canalized, too. Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 7 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush Looking at a picture of the ancient Sumerian classroom for scribes found in Shuruppak (from ca. 3200 BC) for the first time in Edward Chiera’s They Wrote on Clay,7 I immediately was struck by the familiarity of rows of stone benches and the headmaster’s desk up front. Then I was seized with a terrible recognition: Five thousand years later, most children are still sitting in classrooms that enforce the linear discipline of writing in virtually the same methods and with not so dissimilar effects as did these ancient Sumerians, "that gifted and practical people" as Edward Chiera calls them in his groundbreaking work, Sumerians invented cuneiform as a perfectly portable means to effect commerce, extend the authority of their kings, preserve metaphysical and transcendent information, and secure the stability of caste and rank. Teaching in this physical format was self-reinforcing, and education was a means to its own ends. The invention of pictographic writing by the Sumerians was "a secret treasure or mystery which the laymen could not be expected to understand and which was therefore the peculiar possession of a professional class of clerks or scribes,” Chiera writes. Furthermore, the metaphysics associated with this new telepathic technology becomes clear in the priestly functions these scribes served. Neo-Babylonian texts used the same ideogram for priest and scribe. Along with the script came a new mythology that, predictably, placed the power of language in the center of its metaphysics: "As for the creating technique 7 (Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press: 1938). David Porush attributed to these [new] deities, Sumerian philosophers developed a doctrine which became dogma throughout the Near East -- the doctrine of the creative power of the divine word. All that the creating deity had to do, according to this doctrine, was to lay his plans, utter the word, and pronounce the name.” In fact, everywhere pictographic writing makes its advent, we find the sudden emergence of what we can think of as "tech writing empires": civilizations geometrically akin in their compulsive rectilinearity to the hexagonal hive structures of bees. In China, among the Aztecs of Mexico or Incas in Peru, in Babylon, Sumeria, and Egypt, we see the same pattern of physical, social, epistemological, and metaphysical organization. Along with writing come other inventions so predictably similar that they seem to derive directly from imperatives in the nervous system itself amplified or newly grown by use of the new cyborg device of writing: centralized authority in god/kings; monumental ziggurat-like or pyramidal architecture; The Ziggurat of Ur Monumental buildings announce the imperial success of this form immortalized as the Tower of Babel. Mayan Pyramid Chichen Itza Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 9 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush Aztec Pyramid Chinese Pyramid hierarchies of priest-scribes; complex, self-perpetuating bureaucracies; fluid but clearly demarcated social/economic classes; trade or craft guilds; imperialism; slavery; "canalizing" educational systems; confederations of tribes into nations; standardized monetary systems and trade; taxes; and so on. Almost every conceivable aspect of empire, in its gross forms, was enabled by pictographic writing. Eventually, pictograms even enabled a kind of primitive animation through the use of cylinder seals. A cylinder with hieroglyphs incised in clay was rolled along a flat sheet of wet clay to produce an image like the following: David Porush A Cylinder Seal I think of this as the world’s first animated gif: a simple set of images repeats endlessly to create an animated event or story. The general point is taken: with the twinned advent of scratching lines on clay in the earth to farm it and scratching lines on clay tablets to communicate comes a collective, consensual hallucination of linearity that virally dominates every culture which discovers those inventions, and impels certain behaviors: monumental architecture, bureaucratic and hierarchical organization, urbanization, centralized command & control, reliable replication of instructions and therefore mechanization of labor, etc. Further, in the early experiments with that linear form, we can see even now five thousand years later the traces of today’s epistemology, sciences, and communications arts such as computer programming and animation techniques, symbolized in the cylinder seal. Jacques Derrida discusses the cognitive-cultural revolution brought by the advent of writing in his extended admiration and critique of Leroi-Gorham’s work on the evolution of writing La geste et le parole8. As Derrida notes, if a bit dramatically, the advent of writing brought into being "limits." It produced homogeneity, a "mundane concept of temporality… and the linear,” and this model of the line was the substrate of all subsequent philosophy and thought. "The line is the suppression of pluri-dimensional symbolic thought." It produced the "thesaurization, capitalization, sedentarization, hierarchization and the formation of ideology by the class that writes or rather commands the scribes” [86]. Even the alphabet, with its greater efficiency and fidelity to speech, only added abstraction and agility to what Derrida calls “exteriorization,” of technics of thinking, echoing what McLuhan described as the exteriorization of the nerve net: the projection of the dominant habits and inclinations of the collectively cultured mind onto nature. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McLuhan describes the telegraph as an exteriorization of the human nervous system that circled the entire Earth in 8 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1980) Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 11 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush a net of consciousness.9 In some senses, all new communications media tend to and enable this imperial terraforming. Without script, there can be no empire, because the limit a messenger can broadcast a message with fidelity is the limit a man can ride in one day. There are no illiterate empires. With literacy, empire is virtually compulsory. But there was one moment in history, a parenthesis, which radically interrupted this cybernetic feedback loop between writing system and culture/empire canalization. It occurs at the moment that the hieroglyphic/pictographic system is supplanted by the invention of the alphabet. This event is so momentous that it only happens once in all of human history, so powerful that it eventually spreads, and is indeed still spreading, across all human cultures, and so much a cultural bifurcation that one can argue that it is the root of abstract monotheism which arises coeval with the aboriginal alphabet in the midsecond millennium BCE. The moment of alphabetic birth is brief, for it is quickly supplanted by improvements on its own fundamental innovation. Yet it evolves along its own path in dialectic with the totalizing line of empire that is taken up again when the alphabet evolves enough to be harnessed to the work of the tech-writing pictographic scripts. In other words, the birth of the alphabet starts a radical vein in history that persists today, if we look for it. But it is soon swamped as, like other scripts, the alphabet evolves into a tool for empire. We can locate this moment, this interruption, eruption, parenthesis, this invention on the margins of culture, as an evolving complex wedded to the ancient alphabet. It has some stable morphological features associated with the culture of people who still use that alphabet, Hebrew. Indeed, some Jews believe that the Hebrew alphabet was divinely inspired. Certainly, the Hebrew Bible – the Torah – codifies a new ethos, morals, set of laws, and concept of divinity that was unprecedented, and that codification and conception was impossible without the abstract capabilities of the early alphabet. Phoenician, Ugaritic, Greek, Glagolitic, Arabic, Aramaic, Amharic, Hongul [Korea], Russian, Latin, and all Indo-European alphabets derived from this ancient Hebrew script, also known as “proto-Sinaitic.” Every other writing system is either pictographic (Chinese, Egyptian hieroglyphic, Aztec runes, etc.) or syllabic (e.g. Cuneiform A, North American Cree and Eskimo, Vai [Africa], Katakana and Hiragana [the two Japanese Kana scripts invented between 700-900 AD]). Some hybrids - pictographic syllabaries (Tamil, Sanskrit and Cuneiform Linear B or Akkadian) also arise in parallel. Syllabaries are an important step on the road to an alphabet because they shift the representation of language from images of things or events (pictograms, sometimes mistakenly called ideograms or logograms) to the much more plastic representation of the sounds of the language itself. This is the revelation that enabled syllabaries to become more efficient thank pictograms by an order of magnitude, from thousands to hundreds. Nonetheless, syllabaries are a clumsy compromise still requiring an elite and empowered class of scribes to master those hundreds of signs: one for ba, another for beh, a third for bee, a fourth for bo, a fifth for boo, etc. Alphabets reduce the number of characters to 36 or fewer, on average, 25 or 26, mostly consonants, a few vowels. The fundamental revelation of a proper alphabet, and its quantum leap in 9 (New York: McGraw Hill 1964) David Porush efficiency over syllabaries, came from the recognition that signs didn’t need to represent speech sounds, but could represent atoms of sound that are pre-verbal. An alphabet, in other words, recognizes consonants as separate and constant elements permuted around another constant set of explosives -vowels -- which make the utterance possible. Try speaking the consonant "p" without expelling the air that comes behind it with the vowel, and you will see that all you get is a stutterer's intention to say "peh" or "pah" or "pay," a moment of hesitation before an explosion that can only be propelled by a vowel. This Proto-Sinaitic script, the prototypical and aboriginal alphabet, represented only the 22 alphabetic characters for the consonants but did not conceive of how – or even whether - to represent vowels. This is peculiar, since the "idea" of a vowel is entailed once one makes the phonetic distinction of a "consonant." Perhaps it can be explained by the need for the Hebrews for secrecy, for a code set apart from the reigning script paradigm, implicit in the fact that their earliest alphabetic inscriptions are found in the turquoise mines they worked as slaves for the pharaohs. Or perhaps, more simply, Hebrew was simply an incomplete and primitive experiment, a form of graffiti, that nonetheless produced a powerful, if defective, technology. Or as some epigraphers have explained, the Hebrew borrowed the first sound from the Egyptian hieroglyphs, in a principle called acrophony (the highest or first sound) to form their alphabet. Nonetheless, it is quite possible that the universal literacy among the Hebrew slaves fueled what was eventually the world’s first massive slave release, perhaps by a Pharaoh made nervous by a large population of slaves with this awesome, infectious technology. In any case, the Phoenicians, or some Western Semites with whom the Phoenicians came in contact between the 12th and 9th centuries BC, probably between Tyre (now in Lebanon) and Akko or Atlit (now on the northern coast of Israel) realized the inefficiency or primitiveness of this system and added the missing vowels. The Phoenicians obviously found this new communications technology useful for their commerce and imperialization of the seas. In turn, they pollinate the Mediterranean with it, exporting a new improved alphabet, now a much more efficient device for representing all the sounds of speech, eventually importing it to Greece between the 9th or 8th centuries. At the same time, the alphabet in different forms spread eastward through Persia into India, and westward back into Africa. Illiterate cultures seem to adopt the alphabet more quickly, while strong literate empires (it’s a redundancy; there are no illiterate empires) like Egypt have too much invested to change. The Egyptians’ cultural matrix was too intertwined to give up their form of writing, which as elsewhere (including among the Hebrews) was implicated with their religion, social organization, wealth, and epistemology. As a result, hieroglyphics, with its thousands of pictographic elements, survived into the Roman era, though the Egyptians adopted the acrophonic method to signify sounds after the alphabet was broadly adopted elsewhere. What did the Hebrews do with their new alphabet? First, and most obviously, they wrote: The 22 alphabetic signs enabled anyone to read and write, and the Hebrews did. They invented a new, abstract God: invisible, ubiquitous, omnipotent, who in parallel to the difference between their scripts and those that preceded it, supplanted idols (physical representations). Indeed, the unknowable, unprounouncable, Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 13 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush untranslatable Tetragrammaton – the Name of God -- becomes one of the central transcendentals of the religion. They seemed to think more abstractly and flexibly about inward essences, creating much more refined ethics, more elaborate laws, and less hierarchical social organizations, following the access to knowledge granted by their more demotic literacy. In all, and perhaps most compellingly, the universe of things that could be expressed in writing – and with greater exactitude - grew tremendously, opening up an inner life and a conceptual life for sharing beyond the bounds of space and time entailed by speech. A pictogram is inherently literal; the alphabet, by comparison, inherently metaphorical. The trajectory of communications technologies What are the lessons of this brief history of the alphabet? The evolution of communications technologies traces a definite evolutionary line, obeying laws as surely as those that guided single-celled organisms to their destiny and eventual expression in complex primates. From Sumerian pictograms through the alphabet, the printing press, the telegraph, telephone, television, the Internet, faxes, cell phones, wireless networks, interactive gaming on the World Wide Web, there are some vast but consistent generalizations that hold true: we know that new communications technologies transform culture and cognition by making new ways of thinking possible thrive in parallel with older ones spread with amazing rapidity and force grow more dense, enabling more information to be transmitted in smaller channels require less energy per byte enable the same amount of information to be transmitted faster enable messages to be broadcast wider and further enable new kinds of messages and communications that seem more robust, more able to express new knowledge grow more flexible and easier to use grow more coherent and secure (increasingly less vulnerable to degradation over increasingly great distances) because they are bound up with more universal access and easy redundancies grow more ubiquitous (we inhabit an increasingly dense mediasphere, surrounded by messages in multiple channels and sensory modes) grow more transparent (less ambiguous) grow more networked grow more personalized, more sensitive, more specific -- more intimate! These trends also produce certain ontological effects. To put it plainly: our media enable us to experience our universe differently and more richly. They alter our relations and our sense of ourselves. David Porush Our communications grow, over the centuries, more ubiquitous, more timely to the point of instantaneity – which we have now achieved -- more experiential, more sensory, more interactive and more intimate across a wider reach of people in time and space. We can know more about and respond to each other with greater sensitivity, nuance, and speed. We can summarize these effects as follows: Communication technologies work at increasing distances to shrink the distances between sender and an ever-larger set of possible receivers. They grow better at sharing what I’m experiencing here to what you experience there, and vice versa. They enable increasingly more direct conversations between and among minds. Call it telepathy. The Web is the next step in this evolution towards increasing the bandwidth and fidelity of our telepathy. If you want to transmit your mind so that another person can experience it, the Web may provide the next best way to do it. (I leave it to you to imagine the best way.) On the face of it, it supersedes the alphabet by enabling instantaneous two-way transmission of pictures, texts, images, sound and voice.10 – although partisans will always argue that reading a novel is a better more faithful act of telepathy than surfing the web, just as some defended poetry against the novel, and Plato defended oral culture against literacy, which, he argued, destroys memory. Eventually, the Web may even deliver a good simulacrum of the richness of sensory experience in real reality. The Web already offers a new format for directed imagination and telepathy, a multi-sensory and absorbing hallucinatory journey. We teachers brought up in the old modality of text and test can only perceive dimly the assumptions in the cognition of our students, an hallucination like the letters of the alphabet in a Dr. Seuss’s On Beyond Zebra: “I’m telling you this because you’re one of my friends/My alphabet starts where your alphabet ends.” Short of hallucinating accurately, the only way I can hope to contact those students and my own children, the only way I can hope to design a technology to accommodate their learning style, is by understanding the trajectory of the past accurately and projecting it into their future. The alternative is to promulgate my version of that Sumerian schoolroom. So what sort of pedagogy emerging from what sort of episteme emerging from what sort of metaphysics does the Web promise? Future Vignette First, let’s pause for humility’s sake, cautioned by The Faggin-Gates-Sterling Prophesy about Prophesy: “Most people overestimate what is going to happen in the next two to three years and underestimate what is going to happen in the next decade.” (Bill Gates) “The short term consequences are generally less than we planned while the long-term consequences are much more than we expect.” (Frederico Faggin). “My fellow cyberpunk-science fiction authors and I are constantly being overtaken by events.… The 'cycle time' of modern inventions outstrip our imaginations.” (Bruce Sterling). In short, prophesy at your own risk or get out of town before your predictions come due. To prophesy is to sail parlous waters. Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 15 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush There are several excellent prophesies in science fiction, especially cyberpunk, of how virtual reality and networked computing will enable new modes of education. All of them imagine concentric rings or spheres of knowledge that a learner must navigate through by passing tests or solving puzzles. Of course, this follows both the archetypes of heroism and the design of all human educational systems, but when reflected back to us in these works of fiction containing transcendental mysteries at their core, they obtain compelling qualities in the context of the computer media that enable them. The most striking of these include The Diamond Age by Neal Stephenson (1995), Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card (1984), “I can remember it for you wholesale,” by Philip K. Dick (1966), and Neuromancer, quoted in the epigraph to this chapter, by William Gibson (1984). The most chilling, however, is not from an acknowledged author of sf at all, but from Derrida. In a little-noticed passage in Of Grammatology, Derrida suggests that there is an actual feedback loop between our imperially linear media and our bodies. We project more and more limiting – if efficient - modes of behaving from our more and more linear modes of thinking, and we grow ever-more dependent on those technologies. We become softer and weaker and more efficient. He imagines, in a dark vision of posthumanity worthy of the “The Matrix,” the end result of the evolution of humans under the dominion of linearity: he sees "a man of the future who will no longer be a man." This man, even though he still has his teeth, his hand, his upright posture, will be "...a toothless humanity who would exist lying down using what limbs it had left to push buttons...," a button-pushing prone post-human. However, Derrida sees hope in the emergence from philosophy, science and literature of “non-linear writing.” As Derrida exclaims, non-linear writing "means the end of the book even if today it is within the form of the book that new non-linear writings - literary or theoretical - allow themselves to be, for better or for worse, encased." But in any case, this is not a matter of submitting to the book or not, or of finding some other form, since the non-linear history of writing was always already there, waiting to be discovered by a new or different kind of reading, a kind of proper philosophy -- Derrida's in fact - that would "read what wrote itself between the lines of the volume." So to a deconstructive perspective, even the book is already a non-book or other-than-book. "Beginning to write without the line, one begins to reread past writing according to a different organization of space… Because we are beginning to write, write differently, we must reread differently. …For over a century, this uneasiness has been evident in philosophy, in science, in literature. All the revolutions in these fields can be seen as shocks that are gradually destroying the linear model.… What is thought today cannot be written according to the line and the book." (87) “We’ve lived so long under the notion of the Web as a space of connected documents, it seems almost unthinkable that it could be organized any other way. But it could just as easily be assembled around a different axis: not pages but minds…a matrix of minds.” – Steven Johnson, Wired (June, 2003):158. 10 David Porush Writing before the advent of the Web, Derrida imagines the Web, which is nothing less than a totalizing and universal medium that enables and expresses this growing Western movement towards the anti-linear. At the core of the Web is hypertext (thus the http: at the beginning of all URLs, I remind my younger audience: HyperText Transfer Protocol”). At the core of hypertext is the “A HREF…” command, linking (in theory) any part of any document anywhere on the Web to any other target document anywhere on the web. The Web thus is intrinsically a technology that breaks the linear paradigm begun more than five thousand years ago with the advent of writing. That new medium promotes decentered authority, multivocality, and self-contextualizing knowledge. It promotes surfing and contingent discoveries. It gives our students and children a terrible, wonderful gift: the assurance, illusory or not, that just about everything that is known is accessible by a few clicks on keyboard and mouse. The gods have come to Earth. Just ask the question the right way and you will get an answer. No…more answers than you can imagine. Now imagine a whole generation of students who didn’t learn this but were born in it. No wonder, then, that the NextGens are both masterly at navigating our online courses in the simpleton organization of knowledge provided by our Learning Management Systems – and they are bored by it. If we understand the real meaning of both the communications revolution and the tension between linearity and non-linearity enacted in the Web, we therefore are forced to face our terrible, wonderful responsibility in response to the gifts it brings: the Web demands that we invent a new paradigm for organizing, representing, and transacting knowledge formation, learning, teaching, and understanding. What if everyone in the world who learned online learned in a common, interoperable Universal Learning Environment? Imagine this ULE provides Integrated access to a cadre of fellow learners Intimate and continuous feedback and guidance from a professor Immediate selection from a universal library of interlinked, interactive multimedia learning objects, experiences, performances, immersions, animations, sounds, simulations, texts, recordings and broadcasts Highly personalized, intelligent, sensitive learner-path feedback and guidance, and as a reward Successive access to more specialized cadres of learners and practitioners in the disciplines and the fields Imagine the following scenario – certainly not utopian, perhaps a bit dystopian and mundane – of what a student’s experience might be like in the near future if learning technology were as universal as the alphabet and followed the same trajectory as other communications technologies. I use the military example largely because it is transgressive to you, my reader, here in Second Life. My motivation is to suggest that technologies are politically agnostic even if they are metaphysically vectored: Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 17 Teaching Telepresence and Telepathy David Porush Jill’s on a battlecruiser somewhere in the Pacific. She has completed her two-year Associate’s Degree in engineering technology through a combination of the eNavy U program, passing virtual equipment certification tests while at sea, and credits she completed at a local community college. She now is finishing a Bachelor’s degree in Chemical Engineering while completing her tour of duty. She has chosen to matriculate in a SUNY program, partly because she grew up in upstate New York and attended one of SUNY’s community colleges, and partly because it was SUNY created a cross-campus engineering degree completely online, including tests, simulated labs, and the pooled resources of multiple campuses and partners in the private sector, two decades earlier in 2005. Security, local configuration, and US Navy-specific issues aside, the courses for naval personnel use the same course management system standards as most every institution in the world. When she enters her course, she walks through a personalized portal that “bookmarks” (now an ancient metaphor) her place in various projects and assignments: as she opens the door, it talks to her, and she sees a 3D room exactly as she left it. In the room, there is a desk with books and notebooks, and also a couple of doorways. Jill goes to the desk and picks up her notebook. She leafs through the pages, which combine text with graphics. She comes to her last journal entry, and there’s a 3D picture of a synthetic copper protein molecule that has interesting applications in biochips used in human brain-computer interfaces. She touches the 3D image, and it rotates. She touches one of the chemical bonds and she zooms into it. She can hear tones that vibrate at frequencies proportionate to energies in the bonds. Labels about the energy of the bond and the atomic structure appear. Her own voice starts narrating her latest investigations of the molecule, which she recorded clinically, as a doctor would after seeing a patient. The difference is that her narrative is corrected by a male voice, her teacher’s, who has made both textual and verbal notations about her lab entry. There are also initials from classmates, indicating inquiries and comments which Jill doesn’t have patience for now. Jill is feeling a little lonely in her course, so she calls up one of her Lab Buddies who is also live in the course at the time. It happens to be Hardeep from Mumbai. Jill is late getting her lab report done, and so is Hardeep, as she could see from his open self-report, so they agree to enter the lab together to work. They press the door, and after a moment in which they are authenticated and lots of information is recorded, they enter. Jill grabs her notebook and walks through the Lab door. They switch to public view, which enables them to see other students working in the lab, but almost all on other assignments. They sit down side by side at an electron spin spectrometer. At first they must successfully manipulate a set of controls with certain tolerances, recording readings and performing calculations to exacting specifications. But then, having completed this “test,” they are allowed unusual access to one of the instrument’s controls that pops up on the simulator: they press the button, and they find themselves in a real industrial David Porush lab. There is work in progress on integrating this molecule with an array of other molecules and devices to build a nanobot. Avatars of other researchers – including their professor -- are hovering “inside” at a conference table. They are looking at one particularly mysterious part of the molecule, which has grown enormous. It vibrates in color and gives off numerical readings. Jill and Hardeep join the conversation, having earned a right to do so by performing a unique measurement in collaborating on her spectroscopy assignment. As such, they will share in the patent that emerges from the lab. They are also building relationships with senior researchers in academia and industry at the table… Summary/Conclusions It’s not as if communications technologies evolve by themselves. We build them because humans individually and collectively desire to achieve certain ends. The ten-thousand-year project of building better modes of communication we can fairly say, then, is the result of a collective human desire so strong and instinctive that it persists across time and cultures. The desire to achieve mind-to-mind intimacy is nothing short of an instinct, and the increasing sophistication of our communications technologies trace a path towards along the arc of that desire. A good plan for promoting progress in online learning will not only chart and aggregate and promulgate successful practices, it will predict the directions from which they will come, plot the trajectory we are going to travel. Between steps on the ground and eyes on the horizon, we can get to where we’re going more quickly. David Porush Distance Learning That Shrinks the Distance page 19