new evidence that among children as young as four, boys are more

advertisement

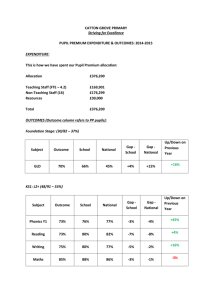

NEW EVIDENCE THAT AMONG CHILDREN AS YOUNG AS FOUR, BOYS ARE MORE COMPETITIVE THAN GIRLS Four year old girls shy away from competition while boys of same age seek the challenge. What’s more, this gender gap in the tendency to be competitive continues throughout childhood and adolescence. These are the key results of a large-scale experiment with more than 1,000 children and teenagers aged between three and 18. The study by Professor Matthias Sutter and Daniela Rützler, presented at the Royal Economic Society’s 2011 annual conference, involved two experiments. The younger children (aged three to eight) took part in a 30m sprint, while older children (aged nine to 18) faced an easy maths challenge, adding up two-digit numbers. In both experiments, the children had to choose whether to perform the task individually or in competition with others. For example, in the maths challenge, children were offered €0.50 per correct answer when performing individually. But when in competition with others, winners of a four person tournament were paid €2 for each correct answer while losers went empty-handed. Although the girls’ maths performance was just good as the boys’, girls expected to do much worse: while roughly two in five boys chose the tournament, only one in five girls did so. Results were similar in the sprint, with girls significantly less likely to want to compete despite having a similar chance of winning. These results might provide one reason why men consistently earn more than women in the workplace. The authors note: ‘To be successful in getting more attractive and better paid jobs in the modern economy, it is important to face up to the challenge of competition instead of shying away from it.’ More… Four year old girls shy away from competition, while boys of same age seek to enter tournaments. Throughout childhood and adolescence, this gender gap in the willingness to compete persists. That is the key result of a large-scale experiment with more than 1,000 children and teenagers, aged between three and 18, conducted by Matthias Sutter and Daniela Rützler from the University of Innsbruck. To be successful in labour markets in terms of getting more attractive and better paid jobs, it is important to face up to the challenge of competition instead of shying away from it. Gender differences in competitiveness therefore have the potential to explain unequal labour market outcomes, such as unequal salaries and glass ceilings. Sutter and Rützler show in an experiment that girls attempt to avoid competitive environments with a much higher probability than boys. The two researchers conducted two different experiments in the field. While the younger children aged three to eight took part in a running task, which incorporated a 30-metre sprint, children aged nine to eighteen performed an easy maths task in which they were asked to sum two-digit numbers. A common feature of both experiments was that subjects had to choose whether to perform the task individually or in competition. In the maths task, the participants were offered a piece rate payment of 50 cents per correct solution when performing individually. But when choosing competition, winners of a four person tournament were paid €2 for each correctly solved problem while losers went away empty-handed. Although girls’ performance in the maths task was equally good as the boys’ performance, girls expected to do much worse than boys. Moreover, while roughly 40% of all boys chose the tournament, only half as many girls (20%) opted to enter the competition. The findings of the running task mirror the results of the math task. The children had to choose between individual performance with lower incentives and a two person competition with double rewards for the winner. Despite similar performance of both genders, girls were roughly 15 percentage points less likely to compete. Given the researchers’ findings of a persistent gender gap already from the age of four, one interesting route for future research is to devise tasks that can be performed with even younger children to see whether the gender gap in the willingness to compete emerges in the first four years of life or whether it seems to be determined by nature. In a follow-up study, Sutter and Rützler are investigating whether different kinds of affirmative action programmes (such as introducing quotas for girl winners or by giving girls a headstart in competition) induce girls to compete more, and whether efficiency does not suffer from these interventions, such as better qualified boys losing out. ENDS ‘Gender Differences in Competition Emerge Early in Life’ by Matthias Sutter and Daniela Rützler Sutter is at the University of Innsbruck and the University of Gothenburg; Rützler is at the University of Innsbruck For further information: Contact Matthias Sutter on +43-512-507-7170 (email: matthias.sutter@uibk.ac.at; http://homepage.uibk.ac.at/~c40421); Daniela Rützler on +43-699-12255735 or +43512-507-7467 (email: daniela.ruetzler@uibk.ac.at) or RES media consultant Romesh Vaitilingam on 07768-661095 (email: romesh@vaitilingam.com)