Autonomic Dysfunction: An Everyday Experience

advertisement

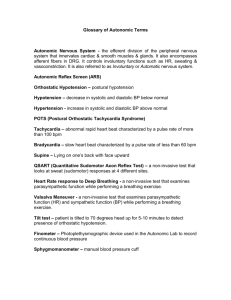

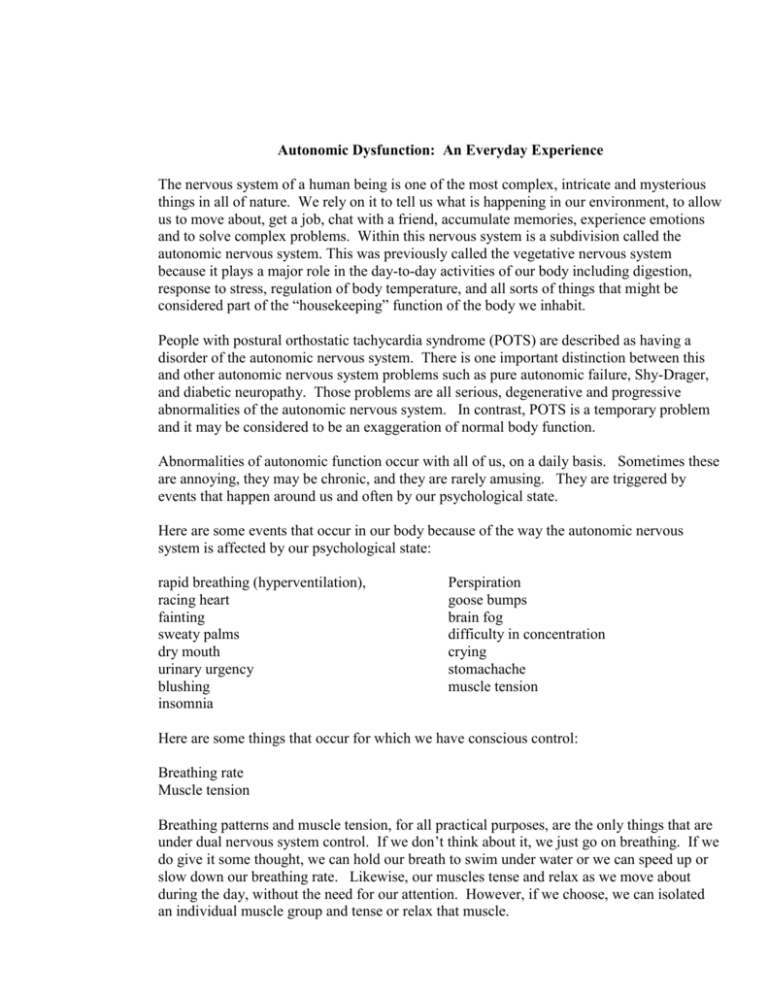

Autonomic Dysfunction: An Everyday Experience The nervous system of a human being is one of the most complex, intricate and mysterious things in all of nature. We rely on it to tell us what is happening in our environment, to allow us to move about, get a job, chat with a friend, accumulate memories, experience emotions and to solve complex problems. Within this nervous system is a subdivision called the autonomic nervous system. This was previously called the vegetative nervous system because it plays a major role in the day-to-day activities of our body including digestion, response to stress, regulation of body temperature, and all sorts of things that might be considered part of the “housekeeping” function of the body we inhabit. People with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) are described as having a disorder of the autonomic nervous system. There is one important distinction between this and other autonomic nervous system problems such as pure autonomic failure, Shy-Drager, and diabetic neuropathy. Those problems are all serious, degenerative and progressive abnormalities of the autonomic nervous system. In contrast, POTS is a temporary problem and it may be considered to be an exaggeration of normal body function. Abnormalities of autonomic function occur with all of us, on a daily basis. Sometimes these are annoying, they may be chronic, and they are rarely amusing. They are triggered by events that happen around us and often by our psychological state. Here are some events that occur in our body because of the way the autonomic nervous system is affected by our psychological state: rapid breathing (hyperventilation), racing heart fainting sweaty palms dry mouth urinary urgency blushing insomnia Perspiration goose bumps brain fog difficulty in concentration crying stomachache muscle tension Here are some things that occur for which we have conscious control: Breathing rate Muscle tension Breathing patterns and muscle tension, for all practical purposes, are the only things that are under dual nervous system control. If we don’t think about it, we just go on breathing. If we do give it some thought, we can hold our breath to swim under water or we can speed up or slow down our breathing rate. Likewise, our muscles tense and relax as we move about during the day, without the need for our attention. However, if we choose, we can isolated an individual muscle group and tense or relax that muscle. In contrast, nearly all of the other manifestations of autonomic nervous system function are not under our control. For example, organizers of athletic events and music concerts know to place a bathroom close to the area where performers warm up. They know that competition leads to increased levels of adrenalin, which in turn causes an increase in urinary output. However, we all know that we can’t just sit quietly and ask our kidneys to produce 10 ml less urinary output per hour, even though that would be a great advantage on those long car trips. Most of us put up with these alterations in autonomic nervous system function and accept them as part of life’s burden. For example, we blush when we are embarrassed, we get a dry mouth when we speak in public, and we get goose bumps when something really gets our attention. A change in autonomic function becomes a disease state that affects our quality of life or when it interferes with our ability to do the things that we enjoy or need to do. There is something we can do about this. We can take advantage of the fact that breathing and muscle tension are under voluntary and involuntary control. Not only that, these functions have influences on all of the other aspects of the autonomic nervous system as well. Let’s just focus on POTS for a moment. The major abnormality is a racing heart rate, which occurs because of increased activity of sympathetic nervous system which produces adrenalin, the stress hormone. The question arises, can we reduce the sympathetic nervous system activity, and reduce the production of adrenalin? The answer is yes. There are specific things that increase the parasympathetic nervous system, the brake, which opposes the sympathetic system, the gas pedal. Slow regular breathing at 6 breaths per minute has been shown to increase the level of parasympathetic nervous system function and restore a more normal heart rate pattern. It is also helpful in relieving and reducing muscle tension. This has been studied scientifically, and reported by Herbert Benson, Ph.D., at Harvard University. He calls his technique “the relaxation response.” Here is a short summary of this method: 1. Sit quietly in a comfortable position. 2.Close your eyes. 3.Deeply relax all your muscles, beginning at your feet and progressing up to your face. Keep them relaxed. 4. Breathe through your nose. Become aware of your breathing. As you breathe out, say the word, "one"*, silently to yourself. For example, breathe in ... out, "one",- in .. out, "one", etc. Breathe easily and naturally. 5. Continue for 10 to 20 minutes. You may open your eyes to check the time, but do not use an alarm. When you finish, sit quietly for several minutes, at first with your eyes closed and later with your eyes opened. Do not stand up for a few minutes. 6. Do not worry about whether you are successful in achieving a deep level of relaxation. Maintain a passive attitude and permit relaxation to occur at its own pace. When distracting thoughts occur, try to ignore them by not dwelling upon them and return to repeating "one." With practice, the response should come with little effort. Practice the technique once or twice daily, but not within two ours after any meal, since the digestive processes seem to interfere with the elicitation of the Relaxation Response. I would recommend that you try this at least once, but preferably twice a day. I think you will find the benefits will be significant. Incidentally, exercise also increases parasympathetic nervous activity. That is one reason why an athlete has such a slow resting heart rate. Felix J. Rogers, D.O., June 2009