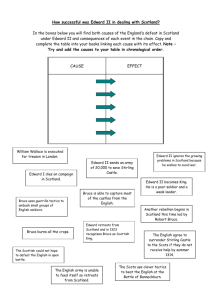

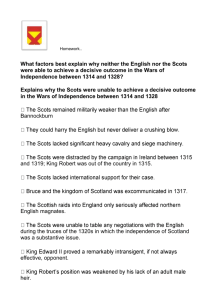

The Scottish Wars of Independence, 1286-1328

advertisement