54. The Roaring Twenties

advertisement

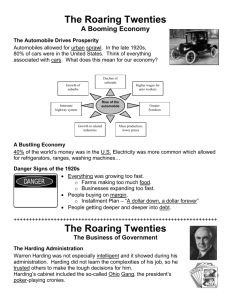

The Roaring Twenties The violence of World War I had a profound impact on the generation of American youth who fought the war either in the trenches of Europe or the factories and farms at home. Beyond the deaths from the war, the Spanish Influenza struck in a worldwide plague killing somewhere between 20-40 million people. A US soldier returned from Europe sick with it and was sent to Ft. Leavenworth in Kansas just as if an enemy planned a direct hit at the center of America with a biological weapon of mass destruction. In seven days, the flu spread across the entire country and killed 675,000 Americans by the end of 1918. The Civil War had only killed 650,000. World War deaths and flu deaths contributed to a social revolution that produced what was called the “Roaring Twenties.” If you are more musically inclined you can consider that the social revolution steeped in death produced the first indigenous style of music that America would export—the new “negro music,” jazz. The Roaring Twenties “roared” partly because of this off-beat music. This decade in US history is also known as The Jazz Age. The year of peace in Europe, 1919, brought more violence at home in the US. In January, shipyard workers in Seattle struck for higher wages, organized a general strike, and paralyzed the city. At the mayor’s request the federal government sent in the Marines! In May, four hundred soldiers and sailors sacked the offices of a socialist newspaper, the New York Call, and beat up the staff. In the summer, race riots erupted in twenty-five cities across the country; the most serious outbreak was in Chicago where 38 were killed and more than 500 injured. In September, the Boston police force struck for the right to unionize, and the city experienced a wave of looting and theft until leading businessmen and Harvard students restored order. Also in September, 350,000 steelworkers struck for the right to unionize and for an eight-hour day. In November, a mob in Centralia, Washington, dragged IWW agitator Wesley Everett from jail and castrated him before hanging him. In December, agents of the Labor Department rounded up 249 Russian-born American communists and deported them to Finland. These events just prior to the decade of the 1920s foreshadowed great changes. Seldom, however, has a generation given so little of permanent value and so much that was troublesome to those who followed. The whole country shuddered at the carnage of The Great War. Wilson’s attempt to spread Progressivism to the international level proved to be a failure as the Progressive Movement found itself unequal to the task of solving the world’s problems. Wilson’s stroke was symbolic of the crippled reform movement, and big business was back in charge for over a decade. Henry Ford created the $5/day minimum wage, turning his own workers into consumers along with most other Americans who could now afford the Model T because of the efficiency of the assembly line. Assembly line work, however, was repetitive and dampened the spirit of craftsmanship since the line between skilled and unskilled labor was blurred. Once General Motors Company (GMC) responded to Ford’s success by offering cars on installment credit, our consumer-based economy was born. Still, Henry Ford is the last great rags-to-riches American Dream story, and he fancied himself a societal engineer as well as an automobile manufacturer. The Republicans who swept to power in 1920 returned the emphasis of the federal government from the reformer to the businessman. The winner in 1920, Warren G. Harding, placed William Howard Taft where Taft had always wanted to be in the first place—Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The Taft Court was known as a staunch conservative bench that allowed employers to fire employees for being in unions. Only a few states passed anti-child-labor laws which most conservatives viewed as unconstitutional. The 1920 saw the First Red Scare, an anti-communist backlash to the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Many Americans were anti-labor, anti-radical, and anti-Southeastern-Europeans and communists were all three. The labor violence across America created one of the first times civil liberties were suspended to ensure greater national security. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer made “clear and present danger” the test excusing the raiding of labor headquarters in search of Bolshevik literature. “Palmer Raids” continued until he was nearly killed opening a mail bomb. Labor unions said they were merely trying to “cash-in” on the post-war prosperity. Warren G. Harding’s Administration was rocked by scandals as if the Gilded Age had returned. He, like Grant, had difficulty seeing the true character of his “friends.” Harding’s own father said if Warren were a girl he would always be pregnant because he couldn’t say, “No.” Harding said, “I knew I couldn’t be America’s best president, but I wanted to be its best loved [italics mine].” Harding’s presidency is an excellent example of how foolish it is for a leader to try to please everybody. In part to shore up his reputation he embarked on a national speaking tour and died from exhaustion in 1923. His death placed Calvin Coolidge squarely at average on my president chart, the only president to receive that ranking. Coolidge’s greatest accomplishment was to let Andrew Mellon, Harding’s old Secretary of the Treasury, push through significant tax cuts. Mellon created the notion of supply-side economics, although it wasn’t called that until Ronald Reagan adopted the idea in the 1980s. Mellon said if the government lowered taxes, people would use that extra money to invest in business and would expand the economy. Then the government would make more money on a larger economy with lower taxes! Mellon’s idea worked for both Republicans like Reagan and Democrats like John Kennedy. First, though, it worked for Coolidge who dropped the national debt $10 billion. Labor unions, again, said that they should demand more during fat years than in lean, and the Coolidge prosperity made most of the economy fat. Farmers, however, entered the Great Depression immediately after the end of the World War I since they no longer were feeding European allies. Even blacks began to demand more through the efforts of leaders like Marcus Garvey of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Garvey dressed flamboyantly and coined the phrase, “Black is Beautiful.” He represented the next step forward for blacks’ civil rights. Having been received as equals by the French when they fought in WWI, they returned less satisfied to cower under the reign of Jim Crow. Writers reacted to and contributed to the changes they observed in American society. Many of them openly rejected traditional American values and traveled abroad in search of a culture. Together, authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Sinclair Lewis are known as the Lost Generation. They were “lost” in many ways including the expatriation of T. S. Eliot and the eventual suicide of Hemingway who had served as an ambulance driver in Europe during the war. All these authors criticized the spoiled, materialistic American society born of The Great War. They described the US as amoral. Young Americans, especially, had ceased asking if their behavior and values were moral or immoral, and when a person no longer considers the difference between right or wrong he or she is said to be amoral. The Lost Generation also criticized the conformity of American society that was evidenced by nativism and the resurgence of the KKK. The Klan had over 5 million members through the 1920s and expanded its animosity toward blacks to include Jews and Roman Catholics. These serious social conflicts festered while the nation worshipped heroes like Charles Lindbergh for flying a plane across the Atlantic and Babe Ruth for hitting a baseball across a fence more than anyone else. At bottom, Lindbergh’s feat was largely accomplished by staying awake for around 36 hours, and Ruth was also the strikeout king as well as the Sultan of Swat. Both were flawed men to be such publicly adored figures. A clash between Fundamentalist Christianity and Modernism came to a climax in our own state of Tennessee, in Dayton. The trial of John T. Scopes for teaching evolution in his high school biology classroom against state law pitted William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution against the most famous defense attorney in America, Clarence Darrow. Darrow, a professed agnostic, cross-examined Bryan who had placed himself on the stand as an “expert” on the Bible. Remember, Bryan was a politician, not a theologian. Regardless, Scopes was found guilty, but the debate over religion, irreligion, and science had just begun in America. Therefore, the 1920s was a time of tremendous societal flux. The American Expeditionary Force can be seen as a smitten limb that we drew back after the blow of The Great War. The US sought to put the war behind us, and for a brief time we were isolationist again. We restricted immigration at the very moment millions of Europeans from the Allied Powers as well as the Central Powers wanted to escape the devastation there and seek their own American Dream. The American soldiers who survived to return home came back changed. Some doughboys had never left the farms on which they were born yet returned from Europe having debauched themselves in Paris. New inventions joined with the new “morality” of a societal and sexual revolution to transform American life. These changes stemmed from insecurity associated with a brush with death. The dual result of this reaction was a despising of who or what was different and a rejection of traditional values.