Solon and the Rhetoric of Philosophy in Plato`s Dialogues

advertisement

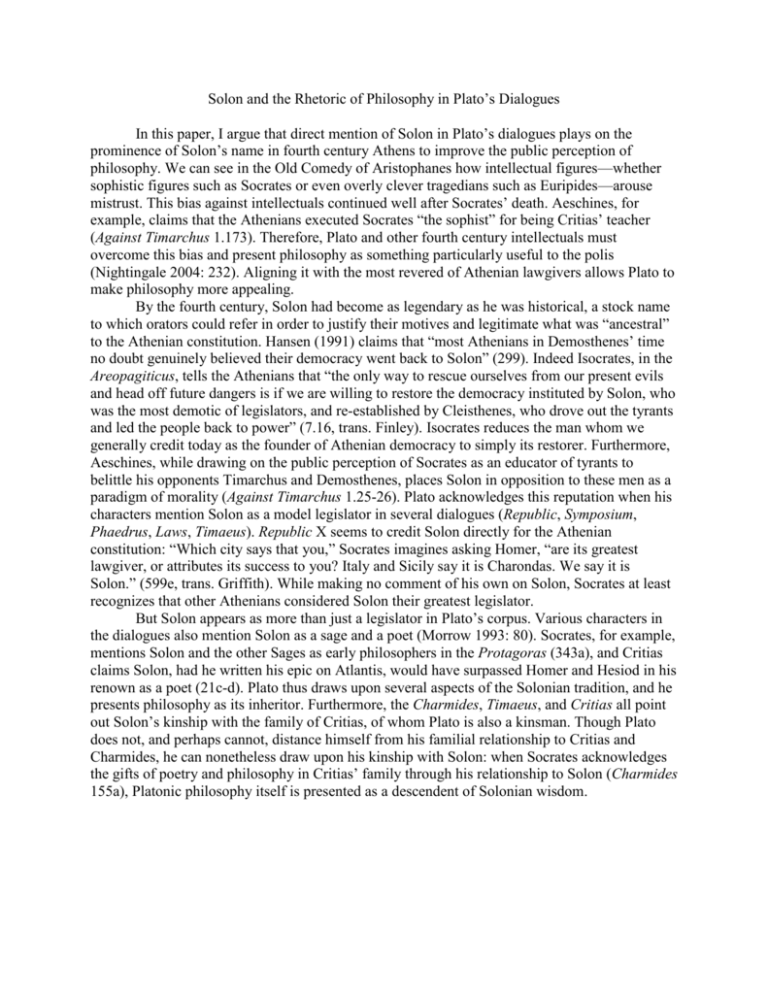

Solon and the Rhetoric of Philosophy in Plato’s Dialogues In this paper, I argue that direct mention of Solon in Plato’s dialogues plays on the prominence of Solon’s name in fourth century Athens to improve the public perception of philosophy. We can see in the Old Comedy of Aristophanes how intellectual figures—whether sophistic figures such as Socrates or even overly clever tragedians such as Euripides—arouse mistrust. This bias against intellectuals continued well after Socrates’ death. Aeschines, for example, claims that the Athenians executed Socrates “the sophist” for being Critias’ teacher (Against Timarchus 1.173). Therefore, Plato and other fourth century intellectuals must overcome this bias and present philosophy as something particularly useful to the polis (Nightingale 2004: 232). Aligning it with the most revered of Athenian lawgivers allows Plato to make philosophy more appealing. By the fourth century, Solon had become as legendary as he was historical, a stock name to which orators could refer in order to justify their motives and legitimate what was “ancestral” to the Athenian constitution. Hansen (1991) claims that “most Athenians in Demosthenes’ time no doubt genuinely believed their democracy went back to Solon” (299). Indeed Isocrates, in the Areopagiticus, tells the Athenians that “the only way to rescue ourselves from our present evils and head off future dangers is if we are willing to restore the democracy instituted by Solon, who was the most demotic of legislators, and re-established by Cleisthenes, who drove out the tyrants and led the people back to power” (7.16, trans. Finley). Isocrates reduces the man whom we generally credit today as the founder of Athenian democracy to simply its restorer. Furthermore, Aeschines, while drawing on the public perception of Socrates as an educator of tyrants to belittle his opponents Timarchus and Demosthenes, places Solon in opposition to these men as a paradigm of morality (Against Timarchus 1.25-26). Plato acknowledges this reputation when his characters mention Solon as a model legislator in several dialogues (Republic, Symposium, Phaedrus, Laws, Timaeus). Republic X seems to credit Solon directly for the Athenian constitution: “Which city says that you,” Socrates imagines asking Homer, “are its greatest lawgiver, or attributes its success to you? Italy and Sicily say it is Charondas. We say it is Solon.” (599e, trans. Griffith). While making no comment of his own on Solon, Socrates at least recognizes that other Athenians considered Solon their greatest legislator. But Solon appears as more than just a legislator in Plato’s corpus. Various characters in the dialogues also mention Solon as a sage and a poet (Morrow 1993: 80). Socrates, for example, mentions Solon and the other Sages as early philosophers in the Protagoras (343a), and Critias claims Solon, had he written his epic on Atlantis, would have surpassed Homer and Hesiod in his renown as a poet (21c-d). Plato thus draws upon several aspects of the Solonian tradition, and he presents philosophy as its inheritor. Furthermore, the Charmides, Timaeus, and Critias all point out Solon’s kinship with the family of Critias, of whom Plato is also a kinsman. Though Plato does not, and perhaps cannot, distance himself from his familial relationship to Critias and Charmides, he can nonetheless draw upon his kinship with Solon: when Socrates acknowledges the gifts of poetry and philosophy in Critias’ family through his relationship to Solon (Charmides 155a), Platonic philosophy itself is presented as a descendent of Solonian wisdom. Works cited: Finley, M.I. (1987) The Use and Abuse of History. Penguin. Hansen, M.H. (1991) The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. Blackwell. Morrow, G. R. (1960/1993) Plato’s Cretan City. Princeton. Nightingale, A.W. (2004) Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy. Cambridge.