Coelacanths

advertisement

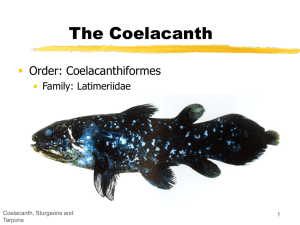

UC Berkeley Researcher Announces Discovery of Sulawesi Coelacanths! 1. Discovery of Second Population: (Use picture of Arnaz with coelacanth, also show maps: Big map of Indopacific, show where Comoros is then inset N. Sulawesi -> Indonesia -> tip of Manado where you can see island of Manado Tua. - I need line drawings from you to give to graphic artist) Until 1938, coelacanths were known only as an order of peculiar lobe-finned fishes which appeared in the fossil record almost 400 million years ago and then seemed to go extinct about 80 million years ago. So the discovery of a live coelacanth off the coast of South Africa in 1938 was understandably met with great excitement. A subsequent fourteen-year search for a second specimen of this extraordinary fish resulted in the discovery of the "true" home of the living coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae, in the Comoran archipelago in the western Indian Ocean. Since that time about 200 specimens of have been caught in the Comoros. Several other specimens have also been caught near Madagascar and Mozambique, but genetic analyses have shown these to be simply "strays" from the main population in the Comoros. The scientific community was shocked again in 1998 when UC Berkeley researcher, Dr. Mark Erdman, announced the discovery of a coelacanth in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, almost 10,000 kilometers from the Comoros. Dr. Erdman first saw a coelacanth in Indonesia in September 1997, while on his honeymoon with his wife, Arnaz. Arriving at a fish market, Arnaz noticed a large, strange-looking fish being wheeled by in a cart. Mark immediately recognized the fish as a coelacanth and excitedly photographed it and briefly interviewed the fisherman. Unfortunately, they did not purchase and preserve the coelacanth. Doubting that they could really have stumbled upon such a major discovery, they concluded that coelacanths must have been found in Indonesia previously. About a week later they found out that this was indeed an important discovery after all. Dr. Erdman returned to Sulawesi in November, 1997 in search of another coelacanth. For several months, he interviewed over 200 fisherman in the coastal villages around North Sulawesi, but few fisherman were familiar with the fish. Finally, he interviewed two fisherman who said they occasionally caught the coelacanth, which they called raja laut, translated as "king of the sea." After careful monitoring of their catch for several months, Dr. Erdman was rewarded with a second Sulawesi coelacanth on July 30, 1998. The second Sulawesi coelacanth was caught by Om Lameh Sonatham in a deep-set shark gill net off of Manado Tua island in the Bunaken Marine Park. The coelacanth was barely alive when it was delivered to Dr. Erdman. After they slightly revived the animal by towing it behind their boat, they photographed it in shallow water. When the injured fish eventually died it was frozen and later donated to the Indonesian Institute of Sciences. Dr. Erdman's announcement of the capture and preservation of a living coelacanth almost 10,000 kilometers from the Comoros was featured in television, radio, and newspaper articles around the world, including CNN, ABC news….. links to these articles? 2. Why all the fuss (Use several pictures of coelacanths with arrows added to point out features - include in captions data on average weight, length, etc.) The fascination scientists and the general public have with coelacanths is likely caused by both its unusual appearance and its evolutionary importance. A unique combination of morphological features suggest that the coelacanth lineage is close to the origin of the evolution of early terrestrial, four-legged animals (tetrapods) like amphibians. The most remarkable of these features is the presence of seven lobed fins, unique among the living fishes. The paired fins move in an alternating fashion which resembles a horse in a slow trot. Other interesting features include a small secondary "epicaudal" lobe on its tail, an oil-filled notochord instead of a backbone, and an intercranial joint which is thought to allow them to widen their gape when capturing prey. While their morphological features lead many scientists to believe the coelacanth lineage was the direct link to tetrapods, recent molecular evidence suggests that lung fish might be more closely related to tetrapods instead. Research in this area remains ongoing. 3. Conservation: (Use picture of fisherman pulling up nets) The coelacanth population in the Comoros is estimated to be in the low hundreds. So the discovery of a second coelacanth population is welcome news for those interested in the conservation of this species. However, we know of only two confirmed coelacanths in Indonesia, the honeymoon fish and the July 1998 fish. Therefore, the population is probably quite small and its discovery should in no way lessen the conservation efforts in the Comoros. Instead, we want to do everything possible to conserve and protect both populations. The people and government of Indonesia have been very quick to accept the responsibility for conserving their coelacanth population. The Indonesian Institute of Sciences have hosted several national meetings to discuss policy issues of further coelacanth research and conservation with fishery, customs, and nature conservation departments, and the Ministry of the Environment. In addition, national pride in the coelacanth has grown thanks to numerous television and newspaper articles and there are plans to distribute educational posters and brochures to schools and villages. What is perhaps most striking about this discovery is that it occurred in an area well-studied by scientists for over 100 years. This illustrates how little we know about even relatively shallow, near shore marine environments…..I need an ending sentence here but I'm not sure what it is yet - any ideas? 4 . Here are just a few of the many unanswered questions that remain about coelacanths: 1. How big is the population in Sulawesi? 2. How long do they live? 3. How old are they when they start to reproduce? 4. How do they reproduce? Although we know females give live birth, there appears to be no external male genitalia, so how does fertilization occur? 5. How often do they reproduce? 6. Where are the babies/juveniles? No one has ever found a juvenile coelacanth, so their habitat or behavior may be different than the adults. 7. How do they use their electrical organ? 8. Do they have predators? If so, who are they? 9. Are the coelacanths in Indonesia the same species found in the Comoros? - This is question is currently under investigation, check back later for more information. 5. Acknowledgements of people who have helped Aided by funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society - anyone else?? 6. Tissue samples requested - What do you want to go in this section? Do you have numbers I can use for this?