Media Representation Theory

Media Representation Theory

Representation refers to the construction in any medium (especially the mass media) of aspects of ‘reality’ such as people, places, objects, events, cultural identities and other abstract concepts. Such representations may be in speech or writing as well as still or moving pictures.

The term refers to the processes involved as well as to its products. For instance, in relation to the key markers of identity - Class, Age, Gender and Ethnicity (the 'cage' of identity) - representation involves not only how identities are represented (or rather constructed) within the text but also how they are constructed in the processes of production and reception by people whose identities are also differentially marked in relation to such demographic factors. Consider, for instance, the issue of 'the gaze' . How do men look at images of women, women at men, men at men and women at women?

A key in the study of representation concern is with the way in which representations are made to seem ‘natural’. Systems of representation are the means by which the concerns of ideologies are framed; such systems ‘position’ their subjects.

Semiotics and content analysis (quantitative) are the main methods of formal analysis of representation.

Semiotics foregrounds the process of representation.

Reality is always represented - what we treat as 'direct' experience is

'mediated' by perceptual codes. Representation always involves 'the construction of reality'.

All texts, however 'realistic' they may seem to be, are constructed representations rather than simply transparent 'reflections', recordings, transcriptions or reproductions of a pre-existing reality.

Representations which become familiar through constant re-use come to feel

'natural' and unmediated.

Representations require interpretation - we make modality judgements about them.

Representation is unavoidably selective, foregrounding some things and backgrounding others.

Realists focus on the 'correspondence' of representations to 'objective' reality

(in terms of 'truth', 'accuracy' and 'distortion'), whereas constructivists focus on whose realities are being represented and whose are being denied.

Both structuralist and poststructuralist theories lead to 'reality' and 'truth' being regarded as the products of particular systems of representation - every representation is motivated and historically contingent.

Key Questions about Specific Representations

What is being represented?

How is it represented? Using what codes? Within what genre?

How is the representation made to seem 'true', 'commonsense' or 'natural'?

What is foregrounded and what is backgrounded? Are there any notable absences?

Whose representation is it? Whose interests does it reflect? How do you know?

At whom is this representation targeted? How do you know?

What does the representation mean to you? What does the representation mean to others? How do you account for the differences?

How do people make sense of it? According to what codes?

With what alternative representations could it be compared? How does it differ?

A reflexive consideration - Why is the concept of representation problematic?

Comparisons with related representations within or across genres or media can be very fruitful, as can comparisons with representations for other audiences, in other historical periods or in other cultural contexts.

Television is... the most rewarding medium to use when teaching representations of class because of the contradictions which involve a mass medium attempting to reach all the parts of its class-differentiated audience simultaneously... Its representations of class can perhaps best be approached by teaching how class relations are represented and mediated within different TV genres and forms

(Alvarado et al. 1987: 153).

Media Semiotics By David Chandler (2006) defines Media representation as:-

“Representation refers to the construction in any medium (especially the mass media) of aspects of reality such as people places objects events and cultural identities. The term refers to the process as well as to its products. For instance into the key markers of identity (class, age, gender and ethnicity) representation involves not only how identities are represented within the text but also how they are constructed in the process of production and reception.”

Representation Theory

What does 'representation' mean?

The easiest way to understand the concept of representation is to remember that watching a TV programme is not the same as watching something happen in real life.

All media products re-present the real world to us; they show us one version of reality, not reality itself.

So, the theory of representation in Media Studies means thinking about how a particular person or group of people are being presented to the audience.

Audience Identification

In a film, the director wants the audience to be on the side of the protagonist and hope that the antagonist will fail.

This means that the audience has to identify with the protagonist – they have to have a reason to be ‘on his/her side’.

But directors only have a couple of hours to make you identify with the protagonist – so, they have to use a kind of ‘shorthand’. This is known as typing – instead of each character being a complex individual, who would take many hours to understand, we are presented with a ‘typical’ character who we recognise quickly and feel we understand.

Character Typing

There are three different kinds of character typing:

1. An archetype is a familiar character who has emerged from hundreds of years of fairytales and storytelling.

2. A stereotype is a character usually used in advertising and marking in order to sell a particular product to a certain group of people. They can also be used ‘negatively’ in the Media – such as ‘asylum seekers,’ or ‘hoodies’.

3. A generic type is a character familiar through use in a particular genre (type) of movie.

Why is Representation Theory useful?

The way certain groups of people are represented in the media can have a huge social impact. For example, would people’s attitudes to asylum seekers change if they were presented differently in the media?

When media producers want you to assume certain things about a character, they play on existing representations of people in the media. This can reinforce existing representations.

At other times, media producers can change the way certain groups are presented, and thus change the way we see that particular group. Changing these representations can also create depth in a character.

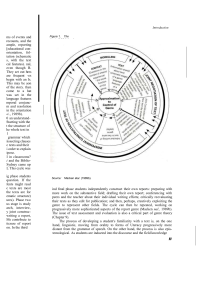

Genre Theory

A genre is, according to David Duff in his Modern Genre Theory (pp. xiii), "a recurring type or category of text, as defined by structural, thematic, and/or

functional criteria." (GenreTheoryCriteria) Genre Theory occurs, following Duff, when we try to understand genres as forming "a coherent system of some kind; ... a theoretical model that offers a comprehensive list of genres and an explanation of the relations between them.

What is Genre?

Genre just means type.

All films and TV programmes can be split into different genres. As with representations, genres draw on pre-existing patterns as ‘shorthand’ for the viewer.

For example, Westerns being set in a desert town, with six-guns and ten-gallon hats).

But sorting film and TV into genres is, as we’ve seen, problematic. There are no set standards for each genre; and there are as many genres as there are ways of describing them.

Genre is usually used in broad terms. For example, Action movies, Westerns, or

Soaps.

There are also sub-genres within each genre. For example, in the genre of ‘Action’, we also find ‘Adventure’ movies (like Indiana Jones) as well as ‘martial arts’ action movies (like the Rush Hour movies – though these could arguably come under the genre of ‘comedy’ and the sub-genre of ‘action-comedy’…)

The Main Genres

Action / Adventure What defines a film's genre?

Comedy Characters

Crime/gangster Mise-en-scene

Drama Narrative

Family Music

Historical / Epic Editing

Horror

Musical

Science Fiction

War

Westerns

But remember: Genre is not 'set' - it is fluid, as it is defined by the audience.

Audience Theory

Audience theory is the starting point for many Media Studies tasks. Whether you are constructing a text or analysing one, you will need to consider the destination of that text, ie its target audience and how that audience (or any other) will respond to that text.

For A level you need a working knowledge of the theories which attempt to explain how an audience receives, reads and responds to a text. Over the course of the past century or so, media analysts have developed several effects models, ie theoretical explanations of how humans ingest the information transmitted by media texts and

how this might influence (or not) their behaviour. Effects theory is still a very hotly debated area of Media and Psychology research, as no one is able to come up with indisputable evidence that audiences will always react to media texts one way or another. The scientific debate is clouded by the politics of the situation: some audience theories are seen as a call for more censorship, others for less control.

Whatever your personal stance on the subject, you must understand the following theories and how they may be used to deconstruct the relationship between audience and text.

1. The Hypodermic Needle Model

Dating from the 1920s, this theory was the first attempt to explain how mass audiences might react to mass media. It is a crude model (see picture!) and suggests that audiences passively receive the information transmitted via a media text, without any attempt on their part to process or challenge the data. Don't forget that this theory was developed in an age when the mass media were still fairly new - radio and cinema were less than two decades old. Governments had just discovered the power of advertising to communicate a message, and produced propaganda to try and sway populaces to their way of thinking. This was particularly rampant in

Europe during the First World War (look at some posters here ) and its aftermath.

Basically, the Hypodermic Needle Model suggests that the information from a text passes into the mass consciouness of the audience unmediated, ie the experience, intelligence and opinion of an individual are not relevant to the reception of the text.

This theory suggests that, as an audience, we are manipulated by the creators of media texts, and that our behaviour and thinking might be easily changed by mediamakers. It assumes that the audience are passive and heterogenous. This theory is still quoted during moral panics by parents, politicians and pressure groups, and is used to explain why certain groups in society should not be exposed to certain media texts (comics in the 1950s, rap music in the 2000s), for fear that they will watch or read sexual or violent behaviour and will then act them out themselves.

2. Two-Step Flow

The Hypodermic model quickly proved too clumsy for media researchers seeking to more precisely explain the relationship between audience and text. As the mass media became an essential part of life in societies around the world and did NOT reduce populations to a mass of unthinking drones, a more sophisticated explanation was sought.

Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet analysed the voters' decisionmaking processes during a 1940 presidential election campaign and published their results in a paper called The People's Choice. Their findings suggested that the

information does not flow directly from the text into the minds of its audience unmediated but is filtered through "opinion leaders" who then communicate it to their less active associates, over whom they have influence. The audience then mediate the information received directly from the media with the ideas and thoughts expressed by the opinion leaders, thus being influenced not by a direct process, but by a two step flow. This diminished the power of the media in the eyes of researchers, and caused them to conclude that social factors were also important in the way in which audiences interpreted texts. This is sometimes referred to as the

limited effects paradigm.

3. Uses & Gratifications

During the 1960s, as the first generation to grow up with television became grown ups, it became increasingly apparent to media theorists that audiences made choices about what they did when consuming texts. Far from being a passive mass, audiences were made up of individuals who actively consumed texts for different reasons and in different ways. In 1948 Lasswell suggested that media texts had the following functions for individuals and society:

surveillance

correlation

entertainment

cultural transmission

Researchers Blulmer and Katz expanded this theory and published their own in 1974, stating that individuals might choose and use a text for the following purposes (ie uses and gratifications):

Diversion - escape from everyday problems and routine.

Personal Relationships - using the media for emotional and other interaction, eg) substituting soap operas for family life

Personal Identity - finding yourself reflected in texts, learning behaviour and values from texts

Surveillance - Information which could be useful for living eg) weather reports, financial news, holiday bargains

4. Reception Theory

Extending the concept of an active audience still further, in the 1980s and 1990s a lot of work was done on the way individuals received and interpreted a text, and how their individual circumstances (gender, class, age, ethnicity) affected their reading.

This work was based on Stuart Hall's encoding/decoding model of the relationship between text and audience - the text is encoded by the producer, and decoded by the reader, and there may be major differences between two different readings of the same code. However, by using recognised codes and conventions, and by drawing upon audience expectations relating to aspects such as genre and use of stars, the producers can position the audience and thus create a certain amount of agreement on what the code means. This is known as a preferred reading

Narrative Theory

In media terms, narrative is the coherence/organisation given to a series of facts.

The human mind needs narrative to make sense of things. We connect events and make interpretations based on those connections. In everything we seek a beginning, a middle and an end. We understand and construct meaning using our experience of reality and of previous texts. Each text becomes part of the previous and the next through its relationship with the audience.

The difference between Story & Narrative:

"Story is the irreducible substance of a story (A meets B, something happens, order returns), while narrative is the way the story is related (Once upon a time there was a princess...)" (Key Concepts in Communication - Fiske et al (1983))

Media Texts

Reality is difficult to understand, and we struggle to construct meaning out of our everyday experience (yeah, too right). Media texts are better organised; we need to be able to engage with them without too much effort. We have expectations of form, a foreknowledge of how that text will be constructed. Media texts can also be fictional constructs, with elements of prediction and fulfilment which are not present in reality. Basic elements of a narrative, according to Aristotle:

"...the most important is the plot, the ordering of the incidents; for tragedy is a representation, not of men, but of action and life, of happiness and unhappiness - and happiness and unhappiness are bound up with action. ...it is their characters indeed, that make men what they are, but it is by reason of their actions that they are happy or the reverse." (Poetics - Aristotle(Penguin Edition) p39-40 4th century

BC )

Successful stories require actions which change the lives of the characters in the story. They also contain some sort of resolution, where that change is registered, and which creates a new equilibrium for the characters involved. Remember that narratives are not just those we encounter in fiction. Even news stories, advertisements and documentaries also have a constructed narrative which must be interpreted.

Narrative Conventions

When unpacking a narrative in order to find its meaning, there are a series of codes and conventions that need to be considered. When we look at a narrative we examine the conventions of

Genre

Character

Form

Time and use knowledge of these conventions to help us interpret the text. In particular,

Time is something that we understand as a convention - narratives do not take place

in real time but may telescope out (the slow motion shot which replays a winning goal) or in (an 80 year life can be condensed into a two hour biopic). Therefore we consider "the time of the thing told and the time of the telling." (Christian Metz Notes

Towards A Phenomenology of Narrative).

It is only because we are used to reading narratives from a very early age, and are able to compare texts with others that we understand these conventions. A narrative in its most basic sense is a series of events, but in order to construct meaning from the narrative those events must be linked somehow.

Barthes' Codes

Roland Barthes describes a text as

"a galaxy of signifiers, not a structure of signifieds; it has no beginning; it is reversible; we gain access to it by several entrances, none of which can be authoritatively declared to be the main one; the codes it mobilizes extend as far as the eye can read, they are indeterminable...the systems of meaning can take over this absolutely plural text, but their number is never closed, based as it is on the infinity of language..." (S/Z - 1974 translation)

What he is basically saying is that a text is like a tangled ball of threads which needs unravelling so we can separate out the colours. Once we start to unravel a text, we encounter an absolute plurality of potential meanings. We can start by looking at a narrative in one way, from one viewpoint, bringing to bear one set of previous experience, and create one meaning for that text. You can continue by unravelling the narrative from a different angle, by pulling a different thread if you like, and create an entirely different meaning. And so on. An infinite number of times. If you wanted to.

Barthes wanted to - he was a semiotics professor in the 1950s and 1960s who got paid to spend all day unravelling little bits of texts and then writing about the process of doing so. All you need to know, again, very basically, is that texts may be

'open' (ie unravelled in a lot of different ways) or 'closed' (there is only one obvious thread to pull on).

Barthes also decided that the threads that you pull on to try and unravel meaning are called narrative codes.

Structure

Tvzetan Todorov - equilibrium, disequilibrium, new equilibrium

Vladimir Propp - characters and actions (31 functions of character types)

Claude Levi-Strauss - constant creation of conflict/opposition propels narrative. Narrative can only end on a resolution of conflict. Opposition can be visual (light/darkness, movement/stillness) or conceptual (love/hate, control/panic), and to do with soundtrack. Binary oppositions.

Separating Plot And Story

Think of a feature film, and jot down a) the strict chronological order in which events occur b) the order in which each of the main characters finds out about these events a) shows story, b) shows plot construction. Plot keeps audiences interested eg) in whether the children will discover Mrs Doubtfire is really their father, or shocks them, eg) the 'twist in the tale" at the end of The Sixth Sense. Identifying Narrator Who is telling this story is a vital question to be asked when analysing any media text.

Stories may be related in the first or third person, POVs may change, but the narrator will always

reveal the events which make up the story mediate those events for the audience evaluate those events for the audience

The narrator also tends to POSITION the audience into a particular relationship with the characters on the screen.

Comprehending Time

Very few screen stories take place in real time. Whole lives can be dealt with in the

90 minutes of a feature film, an 8 month siege be encompassed within a 60 minute

TV documentary. There are many conventions to denote time passing, from the time/date information typed up on each new scene of The X-Files to the aeroplane passing over a map of a continent in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Other devices to manipulate time include

flashbacks

dream sequences repetition

different characters' POV

flash forwards

real time interludes

pre-figuring of events that have not yet taken place

Locating the Narrative

Each story has a location. This may be physical and geographical (eg a war zone) or it may be mythic (eg the Wild West). Virtual locations are now a feature of many newsrooms (eg the computers and holograms of the BBC's Nine O'Clock News).

There are sets of conventions to do with that location, often associated with genre and form (eg all space ships seem to look the same inside).