2012 Self Study - Juniata College

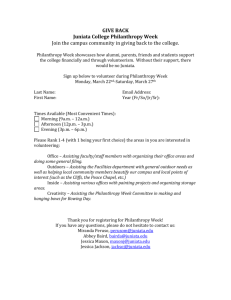

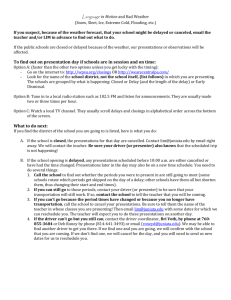

advertisement