The Spread of Agriculture in Asia: Understanding Early Settlements

advertisement

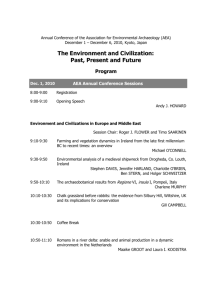

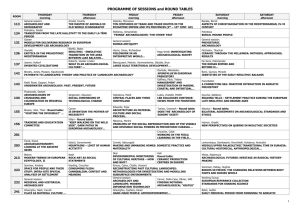

Workshop on “The Spread of Agriculture in Asia: Understanding Early Settlements in the Chengdu Plain” (Report Submitted to the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation) Rowan Flad – Harvard University On October 15th – 17th, 2008, a workshop focused on the spread of agriculture in Asia convened at Harvard University. This workshop was sponsored by the Chiang Chingkuo foundation and the American School of Prehistoric Research. This workshop had a dual purpose. The first was to bring together members of the Chengdu Plain Archaeological Survey (CPAS), who have been conducting a collaborative international archaeological survey since 2005. These scholars presented the methodologies being used for survey in the Chengdu Plain, the history of the project, and the goals for future research. The second purpose was to bring together scholars who have worked on the origin and spread of agricultural practices in different parts of Asia. These scholars both presented on their own research and proposed approaches and research questions that can be considered in the context of the CPAS project. Over the course of two days, 14 formal presentations were given. On the first day, the presentations all focused on the CPAS project and its history and goals. The workshop began with introductory remarks by Rowan Flad, of Harvard University, the workshop convener and organizer. He then proceeded to outline the fieldwork that CPAS has undertaken in two seasons, during the winters of 2005 – 2006 and 2006 – 2007. These two seasons provided an opportunity for the evaluation of various survey techniques in the Chengdu area. These trial seasons resulted in the development of a research strategy that will be employed in subsequent research. This strategy involves a combination of field-walking and auger survey in combination with geomorphological and geophysical research. The results of the preliminary work were presented in a manuscript form to the workshop participants. This manuscript will appear in Chengdu kaogu faxian 成都考古 發現 in a forthcoming issue. A draft of this manuscript is included with this report. The second lecture was given by Gwen Bennett, of Washington University in St. Louis. She presented the history of survey research in East Asia and placed this history in the context of the history of archaeology in China. She focused on the surveys that have been conducted by international collaborative research teams, including the Rizhao survey in Shandong, the Chifeng Regional Survey Project and the Yiluo River Valley Survey. As a participant in two of these three surveys, Bennett was able to describe the differences in their data collection strategies and their objectives. She placed the CPAS project in the context of these projects and discussed the differences in environments, methodologies, data characteristics, and interpretive strategies. She concluded with a discussion of the vexing questions faced by all survey projects that must be considered by the CPAS team. 1 The next lecture was given by Jiang Zhanghua, Assistant Director of the Chengdu City Institute of Archaeology (CCIA). A specialist in the archaeology of the Sichuan Basin and the CCIA director of the CPAS project, Mr. Jiang discussed the history of research on the Baodun Culture in the Chengdu Plain and the details of our knowledge of this culture. The lecture was given in Chinese with English translation by Rowan Flad. The workshop was primarily conducted in English and all of the participants were English speaker or bi-lingual except for Mr. Jiang. Two Ph.D. students, Qu Tongli of Peking University and Lam Wengcheong of Harvard University, provided simultaneous translations of all lectures and discussion points to Mr. Jiang to ensure that everyone could participate in all aspects of the workshop. Mr. Jiang’s talk placed considerable emphasis on describing the nature of archaeological features of the Baodun-culture, including site walls and house foundations. The morning concluded with discussion of the progress and potential of the project and with questions concerning details of the Baodun-culture. The afternoon session included four talks by members of the CPAS project. These started with a presentation by Jade Guedes, PhD student in anthropology at Harvard University. Her presentation focused on the evidence for subsistence practices by ancient communities in the Chengdu Plain and surrounding areas. The presentation relates to a dissertation project being undertaken by Ms. Guedes on this topic, and set the stage for connecting the CPAS project to the question of agricultural origins and development in Asia. Guedes laid out several potential models for both the peopling of the Chengdu Plain and for the emergence of agriculture in this region. She stressed the need to consider the hunting and foraging activities in prehistory as an important component of subsistence practices, even after domesticated plants were present in the region and cautioned against simplistic models of the adoption of agriculture. Guedes was followed by Ed Hajic, an affiliate of the Illinois State Museum who is the geomorphologist associated with the CPAS project. Dr. Hajic spent part of the 2006 – 2007 season in Chengdu and reported on his preliminary reconstruction of the geological stratigraphy in the region. The data presented provide a template for additional research to be conducted in the next several seasons of survey work. They indicate that the cultural material exists in two principal stratigraphic components that require accurate dating. With dates for these strata we will be able to more clearly understand the relationships between changes in the geomorphology and human activity in the Chengdu Plain. This research will be a priority as the project moves forward. Next was a presentation by Pochan Chen of National Taiwan University. Chen has been one of the project organizers since its inception and discussed the problems and prospects facing the CPAS project as it moves forward. He reiterated some of the points made by Flad, Jiang and Guedes concerning the function of walls associated with the Baodunculture, the problems with identifying subsistence practices, and the nature of resource acquisition strategies by prehistoric communities in the region. He concluded by reminding the audience of other resources in the region that must have been important in antiquity, including salt in the form of brine. 2 Salt came up again in the last presentation of the first day. Li Shuicheng, Professor at Peking University, discussed the history of the project in the context of the history of archaeological research in the Sichuan Basin. He began this lecture with an outline of the early archaeological work conducted in the region by missionaries and travelers in the early 20th century. He then discussed the history of the CPAS project itself, which has its roots in a collaboration between Peking University, UCLA, and the CCIA that began in the 1990s. This collaboration involved excavations together with the Sichuan Provincial Institute of Archaeology at a salt-production site called Zhongba starting in 1999. Members of the CPAS project took part in that excavation and that collaboration led directly to the survey project that was the focus of discussion this first day of the workshop. The second day of the workshop turned away from the Chengdu Plain and the Sichuan Basin to other parts of Asia. Seven papers were delivered by specialists on the investigation of the origins and early development of agriculture. These presentations included both a description of previous research and the current state of understanding as well as reflections on the methodologies used in investigating early agriculture in various contexts. The intention was to create dialogue about what strategies might be brought to bear on understanding early subsistence practices in the Chengdu Plain in the context of the CPAS project. The first speaker was Loukas Barton, a recent Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis who currently works for the US National Park Service in Alaska. Barton was involved in collaborative research with various institutions in Gansu and the United States that included excavations at the site of Dadiwan. Within the context of this research, the collaborative team identified very early occupation at Dadiwan which documents the pre-agricultural hunting and gathering populations in this region. Barton discussed one line of evidence that was used in his research on emerging agriculture: isotopic analysis. Through a series of isotopic studies of nitrogen and carbon values in animal bones, Barton presented a convincing argument for a shift from the Phase I Neolithic (8.5 – 7.0 ka) to the Phase II Neolithic (7.0 – 5.0 ka) in the isotopic signatures in animal bones. During Phase I, dogs seem to have been eating C4 plants (probably millet) but pigs were not. In Phase II, pigs and dogs both have elevated d13C values, and humans do as well. He then went on to discuss isotopic studies of human bones from other parts of China as an avenue for understanding the agricultural transition in the Neolithic. The presentation provided an approach that might be considered in the Chengdu region. Following Barton was a presentation by Gyoung-ah Lee of the University of Oregon. Lee discussed ongoing research on the origins of agriculture in both the Korean Peninsula and China. The Chinese material comes from both the Yiluo River valley survey and from recent data collected in the Wei River valley. Lee provided summaries of research on macrobotanical remains collected from the sites of Huizui, Xipo, and Yangguanzhai, among others. She discussed issues that must be taken into consideration during archaeobotanical analyses including sample size, the number of samples taken and taxonomic diversity. Her results have fed an impression of Yangshao subsistence 3 practices that are characterized by multiple cropping, annual scheduling, and low-level food production building on a foundation of low-level food production that seems to have existed during the Peiligang period. She concluded by offering some suggestions concerning topics that require more research focus, including the issue of scheduling and the relationship between subsistence practices and social identity. After Lee, Alexia Smith from the University of Connecticut moved our attention outside of China with a discussion of research on agricultural origins in Southwest Asia. The presentation focused on an approach to characterizing changing subsistence practices over an entire region which makes use of published reports on botanical data. Smith described a database that she has constructed for data from throughout the Fertile Crescent. She discussed the variables that she included in the database, including factors such as researcher, pyric history, number of samples and levels of taxonomic specificity. The database ultimately allowed for a correspondence analysis of data from across a broad region that is informative about regional trends in early plant use. It also brought to light certain plant taxa that were economically important in the past, but which have become undesirable in more recent times. The lecture concluded with a discussion of the importance of considering plant and animal data simultaneously. Smith has led a recent effort to encourage dialogue among plant and animal specialists. Although this has been productive, she mentioned that there is a real need for coordination not only among analysts, but also during the sample collection process. Without coordinated sampling of botanical and faunal remains, the datasets are difficult to compare and use collectively for the purposes of reconstructing subsistence patterns. The final presentation in the morning session was by Dorian Fuller of the University College London. Fuller discussed primarily his research in South Asia, although he brought up many examples from Africa and East Asia, two other regions where he has worked extensively. His paper contrasted top-down and bottom-up strategies using examples from these various regions. Top-down approaches include ethnohistoric and ethnographic studies of plant use in regions and biogeographic approaches. Bottom-up, or inductive, approaches focus on the characterization of regions based on archaeological data collected through fieldwork. Throughout his talk, Fuller stressed the complementarity of these two perspectives. He also used the last part of his talk to discuss efforts to recognize domestication archaeologically. In reflecting on the nature of his work in relation to the CPAS project, Fuller outlined the basic work that needs to be done in order to bring ethnohistoric and biogeographic data into consideration in a region where little research has been done. He stressed that there is often a literature on these subjects that requires extra effort to find, but which can be useful, particularly when one is interested in understanding the entire suite of plants being exploited in antiquity. In the context of the presentation, Fuller provided extensive information on numerous domesticated plants and animals, including millets, sesame, various types of beans, cattle, and rice. In his discussion of bottom-up approaches, he outlined the history of archaeobotanical research in South Asia and what that has revealed about the primary cultivation of staple foods. Finally, he focused our attention on the issue of “silent beginnings,” the early stages in transitions to agriculture that are difficult to identify archaeologically. 4 In the afternoon, three senior scholars in archaeological approaches to the spread of agriculture presented talks. First among them was Zhao Zhijun of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Archaeology. Zhao presented two related topics. He first provided an outline of the big picture of early agriculture in East Asia. He began this part of the presentation with a brief history of the short period of systematic research on botanical remains from archaeological sites in China. This short period of research has been characterized by a recent, rapid development in the field. Not hundreds of sites have been systematically tested and a “bottom-up” picture is beginning to emerge. He identified three regions of agricultural development, North China, the Yangzi River Valley, and South China where tropical agriculture emerged. His talk focused on the data from North China and the Yangzi River valley. He presented data from three case studies to illustrate recent research: Jiahu, Tianluoshan, and Xinglonggou. Each of these case studies has produced some startling results. Grape seeds at Jiahu, for example, were presented, pit of acorns from Tianluoshan were shown to be similar to riverbank leeching pits used for acorn processing in Japan, and millet remains from Xinglonggou are among the oldest known in the world. In the second part of his talk, Zhao turned his attention to the Sichuan Basin. He discussed new results from flotation of samples from five sites around the basin: Haxiu, Yingpanshan, Jinsha, Zhongba, and Maiping. Interestingly, millets are a significant part of the overall plant remains from the region, with rice seemingly a late introduction. The results from these sites will provide a baseline understanding of the region for future work to build on. The next speaker was Ofer Bar-Yosef from Harvard University. Bar-Yosef presented a talk on the big picture of agricultural origins in Southwest Asia with a focus on what we know and a discussion of how we know it. He led the workshop through an overview of some of the most important sites in the Levant including Ohalo, Hayonim, Hallan Cemi, and other Natufian sites, and then Pre-pottery Neolithic A and B contexts at Jericho, Ain Ghazal, Basta, Göbekli Tepe, and others. He then compared the research in the Levant and surrounding areas to recent work in China. He focused in particular on recent climatic research using Chinese data, particularly from speleothems and also on the late Pleistocene remains that have been investigated at cave sites in China from which rice grains have been recovered. Bar-Yosef also discussed early millet producing contexts in Northern China and predicted that even earlier millet producing sites are yet to be found. He believes that the transition to agriculture was probably something that happened first in Northern China, which subsequently affected subsistence in the south. He acknowledged that this is a potentially controversial position and called for more research to address this question so that we may refute or support it in the future The final formal presentation was given by David Harris of University College London. He presented recent research in Turkmenistan as an example of a project that sought to determine whether agriculture began independently with local domestication of plants and animals or was introduced from outside the region. Harris discussed the history of research by the project at the early Neolithic site of Jeitun and attempts to discover preNeolithic sites that might have been progenitors of the 'Jeitun Culture'. The project, which involved collaboration between British, Russian and Turkmen archaeologists, began in 5 1989 and focused on the recovery of evidence of subsistence practices. After a decade of intensive research, the team concluded that Jeitun and related Neolithic sites in southern Turkmenistan and northeastern Iran did not develop from Mesolithic antecedents in the region but were the result of settlement by agro-pastoralists who migrated from the Southwest Asian Fertile Crescent across northern Iran. However, many issues remain unresolved, particularly the nature of interaction between the sedentary Neolithic settlements and contemporary hunter-gatherers, and the possible impact of environmental changes in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. The presentations on the second day of the conference set the stage for a discussion on the third day. Prior to this discussion, workshop participants visited the International Center for East Asian Archaeology and Cultural History at Boston University, the Harvard University Herbaria, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Discussions took place in free flowing exchange of ideas, frequently commenting on the relationships between research done by scholars who presented on the second day and the potential of the CPAS project. The discussion was led primarily by Dr. Richard Meadow of the Peabody Museum at Harvard. Meadow systematically led the discussion through a consideration of various aspects of the presentations from the previous two days. Among the topics of discussion was the need for ways to refine the ceramic chronology of the CPAS project, a suggestion that more “foothill” regions around the Chengdu Plain be somehow incorporated in to the project survey zone, a call for environmental contexts such as buried marshes to be thoroughly investigated in the context of the project, and a reiteration that large numbers of radiocarbon dates will be necessary in the course of the project. Meadow discussed the rapid progress that he has witnessed in the development of the field of archaeology in China and the hope that many of the techniques discussed by scholars on the second day of presentation might become increasingly common in archaeological work in China. The discussion was very conversational, with a wide variety of issues being discussed. Meadow in particular was able to inject ideas that he has developed in research in South Asia into the broader discussion of the emergence and spread of domestication. He emphasized the need to consider the relationship between animals and plants, particularly the effect that the introduction of domesticates into a region might have on the indigenous ecology. This point was reiterated by Harris, who identified three major themes in the workshop: 1) the arrival of new taxa into regions, 2) the relationship between hunter / forager populations and farmers, and 3) how one determines whether archaeological sites were occupied by sedentary populations. Among the various avenues of research that present potential for the CPAS project, the workshop emphasized the following: 1) Isotope work that can evaluate the dietary contribution of different plants to animals, and possibly humans in the survey region. 2) Archaeobotanical sampling of sites in the survey zone but also known sites in the surrounding area, including the foot hills and mountainous areas nearby. 3) Resampling of sites where preliminary research has been done to collect sufficient samples for characterization of subsistence practices. 6 4) Investigation of low-order drainages and buried marshlands to collect botanical data about the ancient environment. 5) Evaluation of whether vegetation refugia still exist in the area where indigenous plants might be collected 6) The construction of a database similar to that used in Southwest Asia to collect the botanical and faunal data from the area as it is generated. 7) Conducting small scale excavations to ensure that some samples can be collected under controlled conditions. 8) Evaluation of whether wood charcoal from survey contexts, exposed strata, or excavated sites can be analyzed effectively. 9) Assessment of the possibility of conducting microcarbon analysis on samples collected from the region. Some of these studies will be made more possible with the introduction of a percussion soil auger into the geomorphological research being conducted as part of the survey. The workshop was a relatively unique experience for many of the participants. It combined an intensive discussion of a research project that is still in the early stages of development with a broad discussion of questions of fundamental importance in understanding any early society. The participants were all enthusiastic about the resulting discussions and we anticipate that the workshop will have a substantial influence over the development of the CPAS project. 7