a transcript of this podcast in form

advertisement

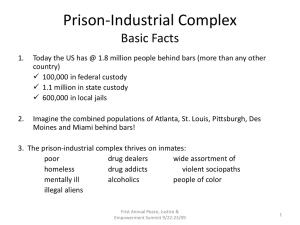

Welcome back to another episode of Bitch Radio. I'm Kjerstin Johnson, web content manager and senior editor of Bitch Media. For this week's show, you'll hear from Eric Stanley, Ralowe Ampu, and Toshio Meronek, who are currently doing a book tour for Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex. I had the pleasure of speaking with them on their stop in Portland. We spoke about the book, what prison abolition means, and how pop culture can reinforce harmful narratives about quote-unquote criminals. Kjerstin Johnson: So, could each of you go around and introduce yourselves with your name and a little bit about what you do and what you’re working on? Eric Stanley: Sure, my name is Eric Stanley, I’m one of the co-editors, along with Nat Smith, of Captive Genders. Toshio Meronek: I’m Toshio Meronek and I work with Critical Resistance, an organization dedicated to ending the prison-industrial complex, and I help mostly with our newspaper, The Abolitionist. Ralowe T. Ampu: Hi, my name is Ralowe, I do queer activism and that’s what I talk about in the book in my piece that I have in the anthology. KJ: Great, well the first question is just talking about what the book is about in general and how it came together. ES: Sure, Captive Genders is an anthology that brings together current and formerly incarcerated people and activists and academics, working around issues of the prison-industrial complex and, specifically, prison abolition, and we wanted to create a space for thinking critically about the ways that trans and queer folks are especially targeted within the prison-industrial complex, and Nat and I started the project around seven years ago, we started by soliciting pieces from people on the inside and friends and allies and people that we knew and slowly amassed the pieces that are currently in the book. KJ: I was wondering if you could describe what’s on the cover of the book and talk about why you picked it. ES: Sure, on the cover is a photograph from the White Night riots, I got it from the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, and when I first started thinking about what was going to be on the cover we knew that we didn’t want pictures of people and so we wanted something that represented abolition and action and not, you know, an incredibly overused barbed-wire or birds flying a cage or prison bars or any of these kinds of things that we think get used too often and the White Night riots were the riots that happened in San Francisco after Dan White assassinated then-Mayor George Moscone and Harvey Milk, after the announcement of his sentence for involuntary manslaughter, and people rioted because of that, and they burned seven police cars, I believe, and one of the police cars in front of City Hall is the cover of the book. KJ: So, could you describe prison abolition to someone who is unfamiliar with it and also, we’ve been talking about why people who care about gay and gender rights should be prison abolitionists. RA: I’ll try very succinctly to kind of explain prison abolition, or the way I think about it when I was writing my piece for the book which is about a hotel, it’s sort of the idea that prisons don’t actually help, they’re not very helpful, they don’t really, they actually cause more harm and sort of, my piece is an example of how expansive this idea of the prison-industrial complex is, that we shortened to the “PIC,” sort of it presents itself in our society in different ways and you really take it for granted, hegemonic things that are all around us, ideas of security and safety. I think of prison abolition of being a way of trying to imagine a world where safety and security that are not things that are given to us by the state but are things that we actually are participating in with the communities around us, because there’s always this really vague idea of exactly what community is and there’s lots of ways to contest it, kinship is not always a given, but I think that a lot of the ways that the state operates is only to further that and further fracture our communities and our connections to everyone, so whenever we have conflicts or whenever there’s harm happening we turn to the state in order to resolve these things, and so I sort of think that this is sort of thinking of a world without prisons, but in this world that we live without prisons it’s sort of saying instead of trying to figure out how to reform prisons or think merely in terms of short-term remedial things only as a way to make prisons safer or better, to try to imagine a world without them and try to imagine a world with all of the things that sort of are accompanied with that policing idea, and surveillance and all of those different things no longer are the background oppression of our lives, that’s sort of my thinking of what prison abolition is, and that’s certainly the way I think about it in my piece, but we can talk about that more later. KJ: Do you want to mention how it works in your piece? RA: My piece is sort of me talking about trying to organize in a residence hotel, which is single resident occupancy, a form of public housing that is like privately-run and is a kind of a designation of housing for people who are formerly homeless, and so you have lots of people who are like coming in there from very vulnerable lives and who are trying to do the independent-living thing, and so you end up in the situation where like–my neighbors are very heavily institutionalized and don’t, they don’t live in a space where they actively practice their own agency in certain ways and they tend to take whatever they can and be grateful for it, because they know if they remain docile they won’t be placed in, you know, they’re in a precarious place, lots of my neighbors tend to be in a precarious place, they might have mental health issues, they might be dual diagnoses, so something that I’ve noticed is that trying to organize in my building around basic things, lots of aspects of my building resemble a prison, it isn’t a prison, but lots of aspects resemble, in terms of restrictions how people come and go, and we can talk more about it, if you read, but it’s sort of like, there’s like people who are unable to imagine actually doing for themselves, and it becomes really hard for me to be like, okay let’s figure out how to change things in the building. So I was talking about the difficulties of that and a lot of the so-called “abolitionists” or the “anti-authoritarian community” doesn’t know how to support people like that or are in those modes of thinking of that certain level of vulnerability, which is one of the big arguments in my piece, if we’re actually going to be figuring out how to do anything, abolitionists need to figure out how to make the spaces where we organize accessible and inclusive of those folks rather than just what has happened, or rather simply it is useful and important to have those messages out there, but I see a lot of shortcomings and feel it isn’t sustainable, a lot of the organizing doesn’t feel sustainable to me. Sorry, that was long. Yeah. T M: You could also, in terms of the ways that this kind of fits into talking about gender and talking about trans people is, I mean, the basic statistics around a lot of these issues. There was a study down in San Francisco that found 70-75% of trans people had been inside at one point or another, so, I mean, just looking at the raw numbers, trans and queer people are policed or surveilled or put inside the system at rates that are much higher than other people. KJ: Coming off of that, what are some ways that the current criminal justice system oppresses and further marginalizes people who are trans? ES: There’s the historic argument that looks at the ways in which, in the United States, at least, gender-appropriate clothing has been policed and mandated through different laws at different moments in time, and currently we see the phenomenon that a lot of people are calling “walking while trans,” and essentially what’s happening is that trans women, trans women of color are always assumed to be sex workers, so vice squads will go around neighborhoods and round up people they assume are trans, and even if they are just locking them up overnight, it’s kind of a phenomenon that happens over and over again, and we see in which trans and queer people are disproportionately kicked out of the homes and schools and many of us end up working in informal economies which predisposes us to the hypersurveillance of those economies and places us within the prison-industrial complex at really young ages, and once you’re in that system it’s really hard to get out of it, because there’s so many barriers of access to education, to work that actually pays a living wage, and so the cycle of violence gets reproduced from an early age. KJ: What are some ways in that mainstream gay rights and feminist movements perpetuate the prison-industrial complex? ES: I think that thinking about how recently Obama, two years ago signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. hate crimes legislature which extended federal hate crimes to gender and sexuality as a class of protected people, and what we’re seeing is the long history of hate crimes legislation works to build up, not diminish the prison-industrial complex, and oftentimes the people that the laws are intended to protect are the same people the laws end up getting used against. In, so that’s one major politic of mainstream LGBT organizing currently, is the push towards hate crimes legislation, and even more recently we’ve seen a kind of term to the antibullying laws that a lot of states are proposing and groups like the human rights program and the NGLTF are also pushing, and there’s one that was recently passed that, an anti-bullying law that was named after an out gay teen that committed suicide because of bullying, but the way that the law actually got put into place, through a mandate by a Republican state legislator, was that it protected people that bullied because of moral or religious reasons, so that it actually created people that bully because of moral or religious reasons as a protected class, so we always have to be careful what we ask for from the state, because everything we ask for gets turned around against us, and I think the mainstream LGBT movement and mainstream feminist movements have never actually gotten the understanding that the state is innately built through misogyny, through homophobia, through racism, through transphobia, there’s no way to make the state as an entity less than of those things. KJ: Well, reading Captive Genders made me think of another book that came out this summer, The Revolution Starts at Home, there’s even some similar contributors, and The Revolution Starts at Home: confronting intimate violence within activist communities, which talks not just about intimate violence not just within activist communities but working outside of the prisonindustrial complex, so, can you speak to some of the crossover between those two? Not if you haven’t read the book, but transformative justice and Captive Genders. RA: I feel like a lot of the Transformative Justice organizing that I’ve been involved with sort of, there’s a way where there’s a really strong synchronicity between these two books, I have sort of, this book is about trans embodiment and queer experience and gender performing experience outside of prison stuff and the prison system, the prison-industrial complex, you know really vast and has different, has had a very vast domain and reach, so there’s focusing on that work and the idea of how to respond to intimate violence, how outside of having to resort to the state, you know, calling the cops on folks, and I feel like a whole lot of the organizing I’ve done definitely, deeply internalizes those views and opinions, and also that philosophy of wanting to do that, and also another book I feel has a strong linkage to this by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, The Color of Violence, which talks about the harm that the prison-industrial complex causes whenever it responds to domestic violence and stuff, and I feel like they are all sort of thinking about the same thing, how can we envision a world outside of that, how can we pull away from that, and of course it’s like, the great difficulty that people fact while trying to do activism is this huge deficit of community or notion of community that can prove unreliable, like how do you make our bonds stronger, how do we figure out how to do the work so we can actually be sustainable and actually be able to deal with each other, and things come up and we don’t have to be like “oh, I’ll just call the cops!” You know, what is the–the policy in my building is that when there’s a person having a crisis you just call 911. KJ: So, especially in the front part of the book, there’s a lot of talk about movements that happened prior to today, especially in the 60s and 70s and it made me think about the current Occupy movement that’s going on right now, so I was wondering how you see again, with the overlap, if there is overlap, if there is room for potential alliances with the Occupy movement, which is being heralded as the new progressive movement, but also criticisms of the Occupy movement when it comes to prison abolition and queer and trans embodiment especially. T M: We were in New York, part of the book tour happened on the East Coast in October, and the Sylvia Rivera Law Project did a really great teach-in that we made it to around making the Occupy spaces safer for trans people, specifically there’s a really great video, you can find it on Youtube, of that teach-in that happened at Occupy Wall Street. ES: Yeah, I mean, I think that I see a lot of potential in the Occupy movement, but also a lot of contestation at a lot of the Occupy spaces that I’ve been to, you know, you see numerous signs calling for the jailing of cops or the jailing of bankers etc., and so it doesn’t have a more systematic approach to these problems that I think our book and the Revolution Starts at Home and Dean Spade’s Normal Life and Queer (In)Justice, which is another book that came out this year, I think that we all take a more systematic or more systemic approach to these problems and know that jailing bankers or jailing cops, not only doesn’t necessarily help us but hurts us because what it does is it reproduces the idea that that system can and with the right people inside the prison, it will be a justice system, so it actually reproduces a lot of harmful logics, like we say “jail cops,” we wouldn’t hold specific cops accountable, what we actually want is a world that doesn’t have cops, that doesn’t inaugurate certain people to kidnap, to murder and hold hostage members of our community, which is the work of the police, and so I think that people have begun doing the work of connecting with Occupy movements and pushing stronger on an abolitionist agenda, and I think what Toshio was saying about the Sylvia Rivera Law project and New York and I know last night, in Occupy Oakland, Angela Davis and a number of other people had a teach-in and there’s going to be fairly soon an Occupy action in solidarity with folks on the inside, working through a number of demands and strategies that people on the inside have created and so it’s a kind of inside-outside solidarity action that’s coming up and I think that I see optimistically as an opening and pessimistically as a reproduction of the same under a different name, but I think that people are attempting to push on it and I think that there is some space there. KJ: How do you see media or pop culture reinforcing ideas about who should or should not be incarcerated and also reinforcing what constitutes a crime and some of these ideas? RA: You know, there’s tons and tons of cop shows and movies about cops and movies about criminals and I think that is just a huge cultural narrative that people, it’s made for entertainment, it’s almost to the point where I can’t actually imagine TV or cinema without those things, I don’t know what they’d put there instead, it’s so taken for granted, and it’s always interesting, if you think about say, what’s the name of that show? Law and Order? They very rarely focus on cops who are in uniform, they are always sort of the detectives that are like dressed, there’s something interesting, they kind of want to, there’s this unwillingness to actually portray a certain kind of interaction that people have with the police, sometimes it is glamorized in shows, it’s just there. I don’t, that is a good question, I don’t what would be an intervention on that, unless people were to have their own network, but it’s so, like, yeah, I don’t know. T M: There’s another show called Bait Car, where there’s actually hidden cameras inside a car that they place in like a quote-unquote “bad” part of town and they wait for someone to come and actually, it’s like GTA live. RA: Oh yeah, Grand Theft Auto... KJ: Maybe a better question is, yeah you’re right, they’re just everywhere, but how do you see these fictionalized and often-exploited images affecting the lives of people who are in prison and are affected everyday by the PIC? ES: I mean, I think that the way, the kind of archetype of the quote-unquote “criminal” like Ralowe and Toshio were saying is a staple in visual and popular culture and it’s used over and over and it’s used to produce a stable identity as someone that produces harm, is always producing harm, is a kind of type of person as opposed to an act that someone might or might not have committed, and I think that that helps inform the way that we understand people who have had specific relationships to the prison-industrial complex, I mean theoretically according to US law, once you’ve served your time, you should be free and clear of those charges, but there’s a way in which the afterlife of the prison-industrial complex is the entire span of someone’s life, things like felony disenfranchisement, where people convicted of felonies are in some states no longer eligible to vote, can’t get certain employment, there’s the box on almost every application that asks “have you ever been convicted of a felony,” or in some places “have you ever been convicted of any crime,” and legally they’re not supposed to discriminate based on that, but as you can imagine, if an employee has a number of applications in front of them, which one are they going to go with, and so I think that there’s a way in that this kind of figure of the “criminal” is so vital to American popular culture, and I think figuring out ways to productively intervene in that is really important, we learn about all of these figures through visual culture and popular culture and so I think that’s a lot of work that abolitionists have to do, is figure out how they’re going to do something differently and intervene in that. KJ: So, what is a good way to start conversations with people about these issues, who maybe think it doesn’t affect them or it’s unrealistic, what have you found as good ways to open that dialogue? RA: I think one strategy, because there’s this way that, prisons exists because they feel necessary, and you know, there’s these really intense situations which you just can’t resolve any other way, I think a kind of useful strategy or exercise is to sort of start with the most extreme example, rather than working from quote-unquote “nonviolent crimes,” like smoking pot or having pot possession, you know, let those people out, because those are things where people are like “well yeah, it’s just marijuana, why are they in jail?” But there are these images of sort of criminals that are beyond any form of forgiveness such as rapists or murderers or child molesters and so forth, I think it’s important to start there and sort of be like, those people deserve to be not inside anymore, it’s like figuring out how to let them be–I lost my thought. It’s just sort of the idea that, again, as I was talking about overall with prisons and having a community and stuff, that would be something that, you know, the community would sort of deal with on a contingency basis and try to figure out, and it’s all about trying build up our capacity and our skills to handle and deal with these issues on that level, which is totally where we are not now as a society, we couldn’t really, people wouldn’t really, people can’t quite even imagine what it would take to do that work. But I think that that’s always a useful exercise to begin with, to try and figure out and imagine how that would look and how that would work. T M: I think also giving people examples of the alternatives that have worked in the past, I know we’re all for examples involved in community mediation around harm, and there’s also a great website called “The Stop Project: Storytelling and Organizing Project,” it’s at stopviolenceeveryday.org, and it’s just a collection of stories from people who have successfully helped to mediate situations where there was harm going on in their communities. KJ: Great, well, those were the main questions I have. Do you want to talk about the book tour at all? T M: So, Captive Genders is available through AK Press, and their website at akpress.org, and this is the Pacific Northwest leg of the tour that we’re on, we’ve visited the East Coast and visited all sorts of cities in October. There are some dates coming up in the Bay Area, in Davis and Berkeley and Santa Cruz, are coming up in February. RA: Come to it. Come out and ask questions and check out the book. T M: Yeah, it’s been great at each of the events, we’ll have a Q & A section at the end and people are telling us about all of the work that they’re doing locally, which is great, we just found out that maybe a Critical Resistance chapter will be formed in Seattle at some point. So, it’s been a learning experience for me as well [laughs]. KJ: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk about this! For more on Captive Genders, visit captive genders dot net, or search for it on Facebook. For links to some of the books, projects, and organizations mentioned in today's podcast, visit bitchmedia.org/audio. If you're a regular Bitch Radio listener, we'd love to hear what you think! We've created a short, ten-question survey about Bitch Radio for you to fill out on our website. Your feedback is critically important to what our podcast sound like, so please visit bitchmedia.org/audio, and look for the link in the right-hand column. Plus, you'll be eligible to win a free, coveted Bitch Media floaty pen! I'm Kjerstin Johnson, thanks again for listening.