Featured Article: Clinical teaching while you work: The One Minute

advertisement

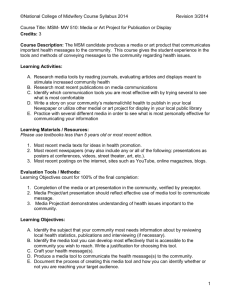

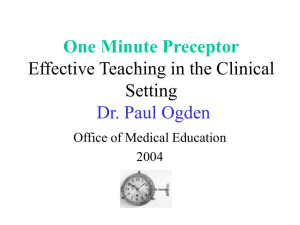

RAP Article Foreword Featured Article: Clinical teaching while you work: The One Minute Preceptor keeps instruction effective and efficient AnnaMarie Connolly, MD • Previous Articles Faculty regularly are asking for materials to help their faculty and reside "teach on the fly". The following article by Dr. AnnaMarie Connolly outli the One Minute Teacher approach along with sample cases that can be u part of a short teacher development program. Clinical teaching while you work: The One Minute Preceptor keeps instruction effective and efficient AnnaMarie Connolly, MD Division of Urogynecology/Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Medicine Chapel Hill, North Carolina ACS Presentations (Resident Work Hours Issues): ACGME Program Requirements Teaching individual learners in the clinical setting has clear appeal and allows instruction in the busy office or hospital-based setting where preceptor, atten and resident teachers deliver patient care. The clear advantages to such teach include one-on-one time with learners, direct observation, direct patient involvement, and "clinically relevant, real-life" scenarios.1 RRC Procedures for Granting Duty Hour Exceptions There are challenges, however, to such instruction. These challenges include pressures of clinical "productivity,"1 diverse educational settings used for clini experiences,2 the "unpredictability" of clinical conditions with which patients p and the difficulty encountered in applying consistent teaching goals or "curric objectives" in these varied educational settings (ie, clinic office, emergency ro operating room).2,3,4,5 Another important challenge to teaching in the clinical is the limited time available with individual patients and/or with individual lea as students and residents are frequently in the office or clinic with preceptors short periods of time. 1 Certainly, strategies to facilitate effective and efficient teaching in the clinical have been identified. These strategies include planning for learners' interactio patients in advance of patient visits,1 teaching during interaction with patients the bedside or in the exam room, and reflecting with learners on patient care has already occurred.1,6 Another effective model for teaching in the clinical se the "One Minute Preceptor."7 While time may be scarce, the One Minute Preceptor helps to efficiently "shap educational discussions and enables faculty and resident instructors alike to effectively teach in the clinical setting.7,8 The strengths of the model are that be taught in a single one-to two-hour seminar and that the model focuses on teaching behaviors that are easy to perform.7 The teacher can "diagnose" the patient as well as the learner and teach the learner by using the following fiv "microskills": 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Getting a commitment Probing for supporting evidence Teaching general rules Reinforcing what was right Correcting mistakes.7 Getting a commitment After presenting the case, the learner usually stops to wait for a response or a guidance from the teacher. Clinical teachers can take this time to get a comm and ask the learner what she or he thinks is going on with the patient. A good example of this first microskill of the One Minute Preceptor could be asking th medical student what differential diagnoses s/he might consider after present 21-year-old patient who has just been seen in the emergency department wit complaints of a 24-hour history of nausea and epigastric pain now localizing t right lower quadrant. Simply telling the student that the patient clearly has ei acute appendicitis or a ruptured ovarian cyst after such a student presentatio would be a bad example of getting a commitment and would not facilitate eva of the student's clinical reasoning. Probe for supporting evidence Before offering an opinion on what is going on with the patient, the clinical te can probe the learner for evidence supporting the learner's clinical reaso For example, in the above presentation, the teacher can ask for supporting hi such as GI and menstrual history. The teacher could probe for supportive sur history such as whether the patient has had an appendectomy and/or any adn surgery. Other supporting evidence the teacher can probe for could include si such as an elevated temperature, abdominal and pelvic exam findings, pertin laboratory findings such as white blood cell count and pregnancy test, as well pertinent imaging such as an abdominal/pelvic CT scan. Alternatively, teacher might ask what other diagnoses were considered and what evidence supporte refuted those diagnoses. A bad example of probing for supportive evidence m include telling the student that a CBC and CT scan were the necessary next st before the student completes his/her presentation or without asking the stude what diagnostic testing and/or imaging s/he thinks would be helpful. Asking le how they interpret data is the first step in diagnosing their learning needs. As them to reveal their thought processes allows teachers both to find out what learners know and to identify gaps. Teaching general rules At this point in the One Minute Preceptor model of instruction, it is time to tea learner. The teacher reinforces general rules focusing on a single teaching poi Using the above clinical scenario, a good example of teaching general rules be reinforcing the difficulty with clinically distinguishing amongst acute appen a ruptured ovarian cyst, or an ectopic, tubal pregnancy. Another good examp teaching general rules in the clinical example would be the importance of orde urine or serum pregnancy test in all reproductive-aged women with right lowe quadrant pain to rule out a potentially life threatening ectopic pregnancy. A b example of teaching general rules could include no such discussion of general rules or simply going ahead and ordering an omitted pregnancy test without informing the learner of the importance of this missed diagnostic study. Frequ what is clinically second nature to the teacher (ie, ordering a pregnancy test i scenario) may be missed by the learner and, as such, these points lend them well to the microskill of teaching general rules. Reinforcing what was correct The next microskill of the One Minute Preceptor is reinforcing what was cor This might include reinforcing that the student's history was complete includin necessary elements and that the appropriate focused physical exam was perf in the presence of the clinical teacher. Reinforcing that the student's presenta was focused, well organized, and easy to follow would also be examples of reinforcing what was correct. A poor example of reinforcing what was correct include no acknowledgment or feedback on the student's history, physical exa and clinical reasoning. Correcting mistakes After reinforcing what the learner reasoned correctly, the teacher then correc mistakes. Discussing missed laboratory testing such as a missed complete blo count or a pregnancy test in the aforementioned 21-year-old female with righ quadrant pain would be an example of correcting mistakes or omissions in the student's work-up of the patient. Common errors in students' clinical reasonin include inability to generate plausible hypotheses or differential diagnoses, inc interpretation of collected data, too much data collection, and an over-empha positive findings. Literature supporting the One Minute Preceptor There are certainly advantages to use of the One Minute Preceptor. The dialog between students and teachers facilitated by this teaching strategy provides students and teachers with multiple opportunities for active learning and prom student-teacher communication. For students, the clinical dialogue allows demonstration of clinical knowledge and reasoning skills while facilitating info feedback sessions. The literature supports that both students and teachers ra One Minute Preceptor as a more effective model of teaching than traditional precepting.9,10 Furthermore, brief, interactive faculty and resident developme workshops, focused on the One Minute Preceptor, have resulted in modest improvements in the quality of faculty feedback delivered in the ambulatory setting11 and resident teaching skills in the inpatient care setting.12 As such, t literature supports the use of the One Minute Preceptor in faculty and residen development workshops designed to enhance teaching skills.11,13,14 The use of role-play with workshop participants taking on roles of "teacher" a "learner" allows for practice with the five microskills of the One Minute Preceptor.13,14 Strategies that facilitate successful use of such role playing to practice the microskills of the One Minute Preceptor include: 1. The use of pre-selected, clinically relevant case scenarios for role play and 2. Overcoming faculty and resident reluctance to participate in role-play activities by providing scripted scenarios for use during role play.13 The case vignettes included in Appendix A provide workshop leaders and participants with clinically relevant materials for role-play practice of the One Preceptor microskills. To help participants overcome reluctance to participate, specific clinical points for the learner to intentionally omit during the role pla session with each case scenario are suggested. This use of intentional omissio facilitates additional practice with the microskills of teaching general rules a correcting mistakes. Summary In conclusion, the One Minute Preceptor is a powerful teaching strategy that c tangibly facilitate effective and efficient clinical teaching between teachers an learners. This strategy promotes student-teacher communication by allowing students to demonstrate clinical knowledge and reasoning and allowing teach diagnose not only the patient but also the learner.1,7-14 References 1. Ferenchick G, Simpson D, Blackman J, DaRosa D, Dunnington G. Stra for efficient and effective teaching in the ambulatory care setting. Aca Med. 1997;72:277-280. 2. Walling AD, Sutton LD, Gold J. Administrative relationships between m schools and community preceptors. Acad Med. 2001;76:184-7. 3. Carney PA, Eliassen, MS, Pipas, CF, Genereaux SH, Nierenberg DW. Ambulatory care education: How do academic medical centers, affiliat residency teachings sites, and community-based practices compare? Med. 2004 Jan;79(1):69-77. 4. McCurdy FA, Sell DM, Beck GL, Kerer K, Larzelere RE, Evans JH. A comparison of clinical pediatric patient encounters in university medic centers and community private practice settings. Ambulatory Pediat 2003;3:12-15 5. Johnson GA, Pipas L, Newman-Palmer NB, Brown LN. The emergency medicine rotation: a unique experience for medical students. J Emerg 2002 Apr;22(3):307-11. 6. Smith CS, Irby DM. The role of experience and reflection in ambulator medical education. Acad Med. 1997;72:32-5. 7. Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step "microskills" m clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:419-24. 8. Neher JO, Stevens NG. The One-minute preceptor: Shaping the teach conversation. Family Medicine. 2003;35(6):391-2. 9. Teherani A, O'Sullivan P, Aagaard EM, Morrison EH, Irby DM. Student perceptions of the one minute preceptor and traditional preceptor mo Med Teacher. 2007;29:323-7. 10. Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the one-minute prec model for diagnosing the patient and the learner: Proof of concept. A Med. 2004;79:42-49. 11. Salerno SM, O'Malley PG, Pangaro LN, Wheeler GA, Moores LK, Jackso Faculty development seminars based on the one-minute preceptor im feedback in the ambulatory setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:779 12. Furney SL, Orsini AN, Orsetti KE, Stern DT, Gruppen LD, Irby DM. Tea the one-minute preceptor: A randomized controlled trial. J Gen Inter 2001;16:620-624. 13. Bowen JL, Eckstrom E, Muller M, Janey E. Enhancing the Effectiveness One-Minute Preceptor Faculty Development Workshops. Teaching an Learning in Med. 18(1), 35-41. 14. Eckstrom E, Homer L, Bowen JL. Measuring Outcomes of a One-Minut Preceptor Faculty Development Workshop. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21:410-414. Resources for Faculty Development Workshop Leaders Appendix A Case Vignettes for Role Playing: Using the One Minute Preceptor Right lower quadrant pain, reproductive-aged female: 35 yo female, with a 24-hour history of nausea, low grade fever, and epigastr now localizing to the right lower quadrant. Example of a clinical fact for learner to intentionally omit: Leave out ect pregnancy from the differential diagnosis and proposed work-up Urinary Tract Infection: 55 yo male presents with a two-day history of painful urination, hesitancy, an urinary frequency. Example of a clinical fact for learner to intentionally omit: Leave out uri stones on the differential diagnosis Abnormal Bleeding Per Rectum: 62 yo female G3P3 presents with a three-month history of irregular blood not rectum. Example of a clinical fact for learner to intentionally omit: Leave out vag source for bleeding on the differential diagnosis Obesity: 50 yo with a three-month history of weight gain. The patient has had to go up clothing sizes and is having an increasingly difficult time exercising as a resul knee and back pain. The patient has several family members with a history of diabetes and she is concerned she may develop diabetes herself. Example of a clinical fact for learner to intentionally omit: Leave out hypothyroidism from the differential diagnosis Online February 26, 2010 Residency Assist Page Division of Education This page and all contents are Copyright © 2010 by the American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL 60611-3211