Overview: The Middle Ages, 1154

advertisement

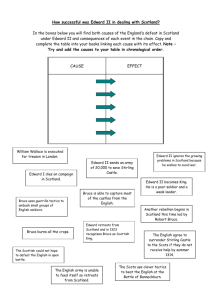

Overview: The Middle Ages, 1154 - 1485 By Professor Tom James Far from their dour reputation, the Middle Ages were a period of massive social change, burgeoning nationalism, international conflict, terrible natural disaster, climate change, rebellion, resistance and renaissance. Norman legacy In December 1154, the young and vigorous Henry II became king of England following the anarchy and civil war of Stephen's reign. Stephen had acknowledged Henry, grandson of Henry I of England, as his heir-designate. His eldest son, Eustace, had died in 1153, but his younger son, who might have succeeded, lived on as count of Mortain. Primogeniture was not then established in England. The Britain of Henry II, and of his sons Richard I and John, was experiencing rapid population growth, clearance of forest for fields, establishment of new towns and outward-looking crusading zeal. 'The families of Balliol, Bruce and Wallace, dominant in Scottish medieval history, all derived from French origins.' The country also witnessed the cultural feast of the '12th-century renaissance' in the arts, exemplified by the Winchester Bible of c. 1160, created from the skins of over 300 calves and lavishly decorated with lapis lazuli and gold applied by a team of manuscript illuminators from continental Europe. Legacies of the Norman invasion of 1066 remained. The aristocracy spoke French until after 1350, so saxon 'ox' and 'swine', for example, came to the table as French boeuf and porc. North of 'sassenach' (Saxon) England, Normanised lowland Scotland (which shared a common vernacular dialect with England North of the Humber) remained distinct from the Highlands where Gaelic flourished. The families of Balliol, Bruce and Wallace, dominant in Scottish medieval history, all derived from French origins - a minority overlaying the population of Scots. Ireland was less dominated by Normans. However, much of the regional indigenous culture survived despite Norman monarchy and aristocracy. English nationalism A combination of external factors made England more inward-looking and more dissonant after 1200. Internationally the crusading ideal was weakening. The Battle of Hattin and the recapture of Jerusalem by Muslims in 1187 were considerable blows to western hopes. Richard I's subsequent failure to recapture the city in his campaign against Saladin was discouraging. Worse still, the crusading ideal was fractured in 1204 with the siege and capture of Christian Constantinople by a crusading force destined for infidel Egypt, and led by Venetians. Crusading never recovered. 'English barons became increasingly conscious of their Englishness, which they declared in anti-foreign attitudes' John's loss of French lands soon after 1200 also made England more inward-looking and frustrated. Population continued to rise in the 1200s, primogeniture became more established and there were many younger warrior sons looking for lands and glory. Henry III (1216 - 1272) was not a soldierly king. His half-hearted campaigns in France were unsuccessful in regaining lands lost by his father, John. By the Treaty of Paris (1259) he admitted failure and secured remote Gascony by giving up claims to lands in northern France, including iconic Normandy. Henry III's reign witnessed many closer links with France, where Louis IX (St Louis) was his brother-in-law. French culture was echoed in Britain, especially in Gothic architecture. But despite Frenchness of manners and names, English barons became increasingly conscious of their Englishness, which they declared in anti-foreign attitudes which focused on immigrant courtiers. It is no accident that scholars have dubbed the spare, simple Gothic architecture of the 13th century 'Early English', epitomised by Salisbury Cathedral, largely built between 1220 and 1258. England dominant Crusading continued during the 13th century, indeed Edward I (1272 - 1307) was away crusading when his father died in 1272 and did not return for two years. Such a smooth transition was a tribute to effective government administration in England. Incredibly, centralised financial record-keeping on the great roll of the exchequer survives unbroken from early in Henry II's reign. Tributes to growing institutions of English government - and hints of a less dominant monarchy are prevalent in this period: 'Expansionism wasn't the sole preserve of England - Scotland regained the Western Isles.' Richard I's realm was governed successfully in his absence for almost his entire reign; Henry III inherited from his unpopular father as a child of nine, with a regency lasting almost a decade; and the transition of power from Henry III to Edward I, when the latter was absent for two years. There was a downside to effective financial organisation. The prosperity arising from peasant agriculture, growing urbanism and burgeoning population growth meant England could focus more directly on its near neighbours Wales, Scotland and to a lesser extent Ireland, in the 13th and early 14th centuries. Wales was partly subdued by Edward I, who put his government's wealth into building the great castles through which he gained control of north Wales. But expansionism wasn't the sole preserve of England. Scotland regained the Western Isles from Scandinavian colonists following the Battle of Largs in 1263. An opportunity arose for England to become involved at the centre of Scottish politics with the untimely death of Alexander III, who died in a riding accident in 1289. Edward I was called upon to judge different claimants to the Scottish throne, which he did, and his pre-eminence is displayed in a contemporary manuscript illumination which shows him with Llywelyn, Prince of Wales, and Alexander, King of Scotland, on his right and left respectively. Rebellion In the last quarter of the 13th century, English dominance over Ireland, Scotland and Wales was apparently being achieved. But that famous image of Edward I with Scots and Welsh rulers illustrates a high point of English predominance. From the last quarter of the 13th century, fundamentals underlying the dynamics of development in Britain and Ireland changed. Population growth slowed down, inflation began to affect wealth and bloody civil war as a way of managing royal power became tempered by embryonic parliamentary developments. 'Rebellions in Wales are testament to some Welshmen's continuing struggle for independence.' Henry III's struggle with Simon de Montfort, who the king defeated and killed at Evesham in 1265, exemplifies this. De Montfort's unofficial 'model parliament' of 1263 and Edward I's official model of 1295 were designed by magnates to curb royal power by increasing representation of counties and boroughs. Problems with the feudal army also emerged at the 1295 parliament when the earl marshal refused to serve abroad unless the king was present. He was threatened with hanging, but neither served nor was he hanged. The remainder of the period from 1300 to 1485 is traditionally seen as a disastrous period in English history, which in many ways it was. However, Scotland and Ireland achieved growing independence during this period. A Scottish highlight in the 'wars of independence' was the victory of Robert the Bruce over Edward II at Bannockburn near Stirling in 1316. The Avignon papacy recognised an independent anointed Scottish monarchy before Bruce's untimely death in 1329, and the long-term 'auld alliance' with France from 1296 secured Scotland's independence. Rebellions in Wales, especially that of Owen Glyn Dwr between 1400 and 1409, are testament to some Welshmen's continuing struggle for independence, although their own princes were replaced by English princes of Wales from the time of Edward I. Famine and plague Remains of Black Death victims, Hythe Ossuary The long view of the period from 1300 to 1485 suggests climate and demographic change were probably key determinants of developments in Britain and Ireland. Climatic deterioration began from about 1300, with colder winters and wetter summers. These conditions contributed to the Great European Famine of 1315 - 1322, in which millions perished. 'The Black Death was the worst disease in recorded history, killing 50% of the population in a year.' Chronic malnourishment weakened the population, perhaps making people more susceptible to the Black Death, the worst disease in recorded history, which arrived in Europe in 1347 and in England the following year. The disease killed 50% of the population within a year, but the main effect was that it returned with alarming regularity in 1361, 1374 and regularly thereafter until it disappeared from Britain in about 1670. The population of Britain and Ireland before the Black Death may have been eight million, of which three-quarters lived in England. Decline continued until about 1450, when the population was perhaps two or three million, the lowest count during the last millennium. By 1485 the population was beginning to rise again. Succession struggle Climate change and plague were not the only external factors to affect Britain and Ireland. The Capetian royal dynasty in France, which had produced male heirs since 987 AD, died out in 1328, provoking a succession struggle in which Edward II and his son Edward (III to be) were prime claimants. These claims lay dormant for several years, as Edward II's French wife Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer invaded England in 1326, imprisoned and murdered Edward II and brought Isabella's son Edward III to the throne in January 1327. Isabella and Mortimer were effectively in power, but in 1330 Edward III asserted himself, had Mortimer executed, and staked a claim to the throne of France. 'Scotland, like England, could function effectively without a king for long periods.' This led to the Hundred Years' War, which lasted from 1337 until the English were defeated and driven from France, except Calais, in 1453. The war was not without English successes both over France (Crécy in 1346, Poitiers in 1356, Agincourt in 1415) and over the Scots (Neville's Cross in 1346). Kings of Scotland spent considerable periods in English captivity, such as David II who was in captivity from 1346 - 1357, and James I who spent 18 of his 31 years as king in prison between 1406 and 1424. But by this period Scotland, like England, could function effectively without a king for long periods. The church and its leading institution, the papacy, like the monarchy so strong in the 12th and early 13th centuries, also became weak and disorganised in the later Middle Ages. The conflict between Henry II and Archbishop Thomas Becket, who was killed in his cathedral church at Canterbury in 1170 by royal knights, was an early manifestation of church-state struggle in this period. A more legalistic approach was followed by Edward I, whose Statute of Mortmain in 1279 was designed to prevent the 'dead hand' of the church gaining further gifts of land to add to its already large land-base, thereby enabling land to circulate within lay society, and making land more easily taxable by the crown. Nationalism triumphs The exile of the papacy from Rome to Avignon from 1305 distanced the English from a papacy seen to be dominated by an increasingly powerful French monarchy. Almost all the Avignon popes and cardinals were French. In 1378, a schism developed in the church, with rival popes based in Avignon and Rome. Inevitably Christendom split and predictably France and Scotland were on the side of Avignon, and England on that of Rome. When the Conciliar movement of the early 15th century was established, no fewer than three rival popes had to be deposed by the Council of Constance in 1417, which duly elected a fourth, Martin V. 'Royal families were so intermarried that mental instability was passed across the Channel.' Division in the papacy exacerbated growing nationalism in western countries. At the Council of Constance representatives voted by 'nations' as England, France and Germany, and later Spain. Throughout Europe, bloody civil wars resulted as rival magnates fought for power during this period. In France some magnates, such as the dukes of Burgundy, sided with the English, prolonging the Hundred Years' War. When the war was over, rival groups of magnates in England fought among themselves. Lancastrians, who had usurped the throne from Richard II in 1399, against Yorkists, whose forebears had a better claim in 1399. Kings came and went, for example Charles VII in France, who was banned from inheritance by his parents in 1420, and Henry VI, deposed in England during the Wars of the Roses. Royal families were so intermarried that mental instability was passed across the Channel from Charles VI of France to his grandson Henry VI of England. Propaganda Upheavals occurred lower down the social scale following the Black Death and during the wars. The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 was one manifestation of this, while Jack Cade's rebellion in 1450 another. In France, the peasant girl Joan of Arc moved centre stage for two years, advising the heir to the French throne and even leading forces in war from 1429 until 1431, when she was captured and burnt as a heretic and sorcerer by the English. The topsy-turvy world of late medieval Britain and Ireland did not stabilise abruptly when, as Shakespeare put it, the Tudor Henry VII rescued the crown of England from a bush on Bosworth Field after the defeat of the reigning monarch Richard III in August 1485. 'Henry V's giant ship of 1,600 tons was a unique achievement and brought peace to the Channel.' Much of what the Tudors claimed as 'new government' was already in place in Yorkist England. War against France and Scotland continued, while Ireland remained semi-independent. At the end of the Wars of the Roses at Bosworth in 1485, England actually came under a Welsh dynasty. Much of the bad press of the 1400s derives from Tudor propaganda. There was, in fact, much to praise in 15th-century Britain. The deafening clash of arms produced as many heroes as villains. The extraordinary Grace Dieu, Henry V's giant ship of 1,600 tons, not rivalled again until the reign of Charles II and Victory, was a unique achievement and brought peace to the Channel, discouraging invasion. Renaissance The renaissance of Chaucer, Gower, Barbour and Dunbar percolated society. Libraries, such as that of Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, were established and the art of biography began. Universities increased in number and scope. Oxford and Cambridge were joined by Scotland's St Andrews in 1410 and two other Scottish universities by 1500. Ideals of internationalism faltered, including crusading, the universal church, monasticism. Nationalism triumphed. Royalty in many respects were as disreputable at the beginning of the period as at the end. 'War and depopulation allowed women to contribute much more effectively and influentially to society.' Throughout England much that we recognise today was established and survives: the parish churches with their towers, now fossilised in their late medieval form by the Reformation; oak-framed timber buildings scattered across the country; universities and schools. Ireland, Scotland and Wales all enjoy similar cultural characteristics. Maybe it was the wars of the period that led the Scots to place their faith in education with their several universities and the Welsh and Irish to develop their bardic and oral traditions during a turbulent but heroic period of British and Irish history. And what of the ordinary people? In 1485 over 95% of the people of Britain lived in the countryside, towns despite their small share of national populations had an impact far outweighing their demographic significance. The period between the Black Death of 1348 and 1485 was, among much else, a golden age for women. War and depopulation allowed them to contribute much more effectively and influentially to society. But the cold wind of climate change, disease and war was by no means to everyone's disadvantage. Find out more Books Medieval Britain: A Very Short Introduction by J Gillingham and RA Griffiths (Oxford Paperbacks, 2000) A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages 1100 - 1500 edited by SH Rigby (Blackwell, 2003) Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology by Colin Platt (Routledge, 1978) This Sceptered Isle, Audio CD Boxes 1-3, 55 BC to 1547by Christopher Lee (BBC Worldwide 1996) The Story of England by Tom Beaumont James (Tempus, 2003) A New History of Ireland: Medieval Ireland 1169 - 1534 edited by Art Cosgrove (Oxford University Press, 1995) The Cambridge Urban History of Britain Volume 1 edited by David Palliser (Cambridge University Press, 2000) The Medieval Town by Colin Platt (Secker, 1976) The Black Death: The Complete History by Ole Benedictow (Boydell, 2004) Medieval Architecture by Nicola Coldstream (Oxford Paperbacks, 2002) Scotland: From Prehistory to the Present by Fiona Watson (Tempus, 2003) About the author Author, broadcaster and lecturer Professor Tom Beaumont James teaches archaeology and history at the University of Winchester. He has published special studies of the Black Death as a turning point in history, and of medieval palaces. He contributed a history of Britain to BBC Worldwide's This Sceptered Isle. Two major publications are out in 2006: The King's Landscape: Clarendon Park (Wiltshire), with Chris Gerrard and The Winchester Census of 1871, with Mark Allen.