Lecture 6 - School of Geography

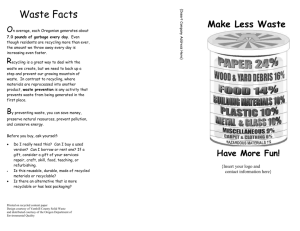

advertisement