Policy for the Establishment and De-establishment

advertisement

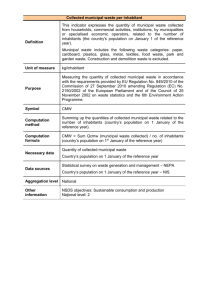

PRESIDENTIAL REVIEW COMMITTEE ON STATE OWNED ENTERPRISES Policy for the Establishment and Deestablishment of SOEs PRC on SOEs: Business Case & Viability Workstream Bongani Gigaba 3/9/2012 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 2. PRC on SOE Problem Statement 3. Focal Point 4. Term of Reference 5. Introduction 6. Initial Assumption 7. Background 8. As-Is (“Status Quo”) 9. Empirical Analysis 10. International Experience 11. Key Findings 12. Recommendations 13. Reference List 1 Executive Summary 1.1 The purpose of this exercise is to conduct an investigation that seeks to determine whether a policy for the establishment and de-establishment of SOEs exist taking into account global best practice. 1.2 In a study conducted by the KPMG on behalf of the PRC on SOEs, it is estimated that circa 502 SOEs i.e. National, Provincial and Local SOEs. 1.3 The majority of the SOEs were established from the late 19the century to date in order to fulfil a specific economic or social responsibility of government. 1.4 Technically, once the state’s policy objective/s is achieved, the relevant SOEs should be dis-established. 1.5 In SA, SOEs are regulated by various pieces of legislation, and policy frameworks. Amongst others, these include the Public Finance Management Act, Municipal Finance Management Act, Municipal Systems Act etc. On 4 April 2004, Cabinet approved as an interim measure, the broad process for the creation of national public entities. 1.6 Our global benchmarking exercise includes China and Norway. 1.7 The key findings of our study could be summarised as follows: That despite its limitations, a policy framework for the establishment and de-establishment of SOEs at national, provincial and local spheres of government exists. The accounting officer for a public entity that is not listed in either Schedule 2 or 3 must, without delay, notify the National Treasury, in writing, that the public entity is not listed. However, this does not apply to an unlisted public entity that is a subsidiary of a public entity, whether the latter is listed or not. As at 30 June 2010, approximately 13 per cent of municipal entities in South Africa could be classified as service utilities. On the other hand, private companies and section 21 companies including trusts accounts for 87 per cent of municipal entities, per type. This is despite Municipalities having been encouraged to take all the necessary steps to convert noncompliance structures like section 21 companies, trusts and other forms. Twenty eight per cent of municipal entities are concentrated in the Development and Planning, and underweight in what could be classified as key service delivery by function. 1.8 Based on the key findings of the exercise, the BC work stream wishes to recommend the following: That the South African government should, as a prerequisite, clearly establish and articulate its goals for State involvement in the economy. 2 That the PFMA should be amended so that the listing of SOE subsidiaries, i.e. Schedule 2 and 3 SOEs, becomes compulsory. Both the MFMA and Municipal Systems Acts should be amended in order to avert the creation and proliferation of non-compliance structures e.g. section 21 companies, trusts and other forms 3 2. Presidential Statement Review Committee on SOEs Problem How can SOEs optimally contribute to development and transformation of South Africa while remaining viable and effective? 3. Focal Point SOEs enabling environment – Legislation, Governance, Ownership, Oversight, Operational structure and systems 4. Term of Reference Policy for the establishment and de-establishment of SOEs 5. Introduction 5.1 The role of SOEs, more especially, after the Second World War continue to occupy a significant role in many countries. In Sub-Sahara Africa, the SOEs remain the key suppliers of social services etc. 5.2 The IMF argues that, “…the inefficiency of the state-owned firms, combined with the attendant state enterprise sector deficits, are hindering economic growth, making it difficult for people to lift themselves out of poverty…” (p1, Bureaucrats in Business, The Economics and Politics of Government Ownership, 1995) 5.3 The above mentioned debate seeks to confirm the importance of a policy for the establishment and de-establishment of SOEs, more especially, in developing countries 5.4 The approach and research methodology to be adopted in this paper is empirical in nature. 5.5 The structure of the position paper is as follows. In Section 1-6, we have briefly reviewed and outlined the brief, PRC’s Problem Statement, the relevant Focal Point as well as the Term of Reference including the initial hypothesis. Literature review will be dealt with under Section 7. In Sections 8 and 9, we have sought to address the background to the Term of Reference including the As-Is Analysis. Global benchmarking is covered in details in Section 10 of this report. The key findings and PRC recommendations are addressed in Sections 11 and 12, respectively. 6. Initial Assumption Assess whether a policy for the establishment or de-establishment of SOEs exist in South Africa. 4 7. Background 7.1 The purpose of this position paper is to determine whether a policy for establishment and de-establishment of SOEs exist in South Africa. 7.2 Basu argues that, “… in an economy there are four types of economic activity: first, those which are privately remunerative - provided by market through Directly Productive Investments (DPI); second, those which are socially profitable but not privately remunerative – provided by State, like road building, irrigation, through Social Overhead Capital (SOC); and third, those which are privately remunerative but not capable of private sector execution, like heavy industry, high technology involving capital intensive investments like power, transportation, etc. – also provided by the State with/without the help of the market; and fourth, those which are natural monopolies. PEs are set up to undertake the second, third and fourth category of activity…” (p11-12, Public Enterprises: Unresolved Challenges and New Opportunities, 2008) 7.3 In a study conducted by the KPMG on behalf of the PRC on SOEs, it is estimated that circa 502 SOEs exist in South Africa. SA’s SOEs straddle across all three spheres of government i.e. National, Provincial and Local. 7.4 The majority of the SOEs were established from the late 19the century to date in order to fulfil a specific economic or social responsibility of government e.g. address specific market imperfections in the economy, service delivery, provide key infrastructure, further enhance SA’s industrialization strategy etc. 7.5 Technically, once the state’s policy objective/s is achieved, the relevant SOEs should be dis-established. To date, empirical evidence seeks to confirm that a number of SOEs specifically at national (i.e. Pebble Bed Modular Reactor etc.) and municipal level have had to be dis-established. With respect to municipal entities, see section 9.3 of this paper. 7.6 In SA, SOEs are regulated by various pieces of legislation, and policy frameworks. Amongst others, these include the Public Finance Management Act, Municipal Finance Management Act, Municipal Systems Act etc. On 4 April 2004, Cabinet approved as an interim measure, the broad process for the creation of national public entities. 5 8. As-Is (“Status Quo”) 8.1 National and Provincial Public Entities 8.1.1 On 4 April 2001, Cabinet approved as an interim measure, the broad process for the creation of national public entities. It is anticipated that the broad process will remain in operation until it has been replaced and/or updated by an appropriate institutional framework for public entities. 8.1.2 Both Ministers of the Public Service and Administration (MPSA) and Finance (MoF) play a key role in the determination of the mandates for the creation, listing and classification of national public enterprises. 8.1.3 The competency of the MPSA is aimed at the proper macro organisation of the Public Service by ensuring that any new or existing public function is allocated / transferred to the appropriate sphere of government, department and/or PE and to eliminate any duplication of functions. In cases where a PE is established for a new or existing function, the MPSA must make a determination regarding the allocation/transfer of such a function to a PE. (p2, Interim Guide for Creating Public Entities at the National Sphere of Government, March 2004) 8.1.4 The competency of the MoF is aimed at the establishment of uniform reporting and listing of all PEs, nationally and in the provinces, by ensuring that any new or existing PE is listed and accountable to Government. This competency involves making a determination regarding the allocation of monies from Government, including statutory funding, to a public entity or future public entity and ensuring that such an entity’s funding requirements and mandate are within the ambit of the MTEF. (p3, Interim Guide for Creating Public Entities at the National Sphere of Government, March 2004) 8.1.5 In terms of the broad interim process, there are four critical steps that should be followed in order to create a national public entity. These are: Step 1: Preparing a business case Step 2: Assessing the business case Step 3: Formalising the establishment of a national public entity Step 4: Implementing the establishment of a national public entity 8.1.6 As it relates to Step 1, an executive authority is required to prepare a business case for the intended national public entity. It should take into account the following i.e. situation analysis and strategic plans, identifying assessing service delivery options, governance issues and recommending the appropriate service delivery option. The projected impact of the proposed national public entity on the operations of the department during the MTEF period should be quantified. 8.1.7 Once an executive authority has recommended the appropriate service delivery option and, submitted the business case, an MPSA and MoF joint evaluation panel will assess the business case for the intended national public entity i.e. Step 2. If the application meets the minimum requirements of both MPSA and MoF, consent will be granted in writing to the establishment of the national public entity. 6 8.1.8 Thereafter, the relevant department must viz. (a) submit the necessary motivation and consent of the MPSA and the MoF to the relevant portfolio committee for discussion before it is submitted to Cabinet; then (b) inform Cabinet of the consent of the MPSA and MoF and request Cabinet approval to introduce a bill in Parliament for establishing the national public entity; then (c) table a Bill in Parliament for establishing the public entity (Step 3) 8.1.9 To effect the establishment of a national public entity (Step 4), the executive must viz. (a) approve the initial organisation and post establishment structure for the public entity; (b) appoint the Members of the controlling body/board for the public entity in terms of its establishing act; (c) in the case where a PE is established for a new function, allocate/transfer resources to the PE where appropriate; (d) effect the transfer of the function and concomitant resources to the public entity based on a number of set principles; (e) request in writing the listing and classification of a public entity in terms of the PFMA; and (f) ensure that the public enterprise complies and submits borrowing programme and budget projection. (p4-8, Interim Guide for Creating Public Entities at the National Sphere of Government, March 2004) 8.1.10 Over and above the relevant policy processes, a policy for establishment and de-establishment of SOEs is regulated by various pieces of legislation. Amongst others, these include the Public Finance Management Act, Municipal Finance Management Act, Municipal Systems Act etc. 8.1.11 In terms of Chapter 6 of the Public Finance Management Act (Act No. 1 of 1999) (“PFMA”), an accounting authority for a public entity, i.e. Schedules 2 (Commercial SOEs) and Schedule 3 (National government enterprises, Provincial government business enterprises, National public entities and Provincial Public entities), should promptly inform the National Treasury on any new entity which that public entity intends to establish or in the establishment of which it takes the initiative, and allow the National Treasury a reasonable time to submit its decision prior to formal establishment. A public entity may assume that approval is granted if it receives no response from the executive authority on a submission within 30 days or within a longer period as may be agreed to between itself and the executive authority. (Chapter 6, PFMA) 8.1.12 The accounting officer for a public entity that is not listed in either Schedule 2 or 3 must, without delay, notify the National Treasury, in writing, that the public entity is not listed. However, this does not apply to an unlisted public entity that is a subsidiary of a public entity, whether the latter is listed or not. (Chapter 6, PFMA) 8.1.13 In the case of unlisted public entities, the PFMA empowers the Minister, by notice in the national Government Gazette to amend the Schedule 3 to include in the list all public entities that are not listed, and make technical changes to the list. (Chapter 6, PFMA) 8.1.14 The following institutions are to be excluded from the Schedule 3 list of listed public entities viz. (a) A constitutional institution, the South African Reserve Bank and Auditor-General; (b) Any public institution which functions outside the sphere of national or provincial government; and (c) Any institution of higher education. 7 8.1.15 The PFMA stipulates that before a public entity concludes any of the following transactions, the accounting authority for the public entity must promptly and in writing inform the relevant treasury of the relevant transaction and submit relevant particulars of the transaction to its executive authority for approval of the transaction: (a) Establishment or participation in the establishment of the company; (b) Participation in a significant partnership, trust, unincorporated joint venture or similar arrangement; (c) Acquisition or disposal of a significant shareholding in a company; (d) Acquisition or disposal of a significant asset; (e) Commencement or cessation of a significant business activity; and (f) A significant change in the nature or extent of its interest in a significant partnership, trust, unincorporated joint venture or similar arrangement 8.2 Local Government Public Entities 8.2.1 In terms Clause 82(1) of the Local Government Municipal Systems Act (Act No. 32 of 2000), “… if a municipality intends to provide a municipal service in the municipality through a service delivery agreement with a municipal entity, it may- (a) alone or together with another municipality, establish in terms of applicable national or provincial legislation a company, a cooperative, trust, fund or other corporate entity to provide that municipal service as a municipal entity under the ownership control of that municipality or those municipalities; (b) alone or together with another municipality, acquire ownership control in any existing company, cooperative, trust, fund or other corporate entity which as its main business intends to provide that municipal service in terms of a service delivery agreement with the municipality; or (c) establish in terms of subsection (2) a service utility to provide a service that municipal service (2)(a) A municipality establishes a services utility in terms of subsection (I)(c) by passing a by-law establishing and regulating the functioning and control of the service utility. (b) A service utility is a separate juristic person. (c) The municipality which established the service utility must exercise ownership control over it in terms of its by-laws...” (p78, Local Government Municipal Systems Act, Act No. 32, 2000) 8.2.2 Chapter 10 (Municipal Entities) of the Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act (Act No. 56 of 2003) states that when considering establishment of or participation in a municipal entity, a municipality must determine the function or service that entity would perform on its behalf and make an assessment of the impact that the shift would have on the municipality’s staff, assets and liabilities. The municipal manager has, in accordance with section 21A of the Municipal Systems Act, make the proposal public and invite local community, organised labour and other interested parties to submit to the municipality comments or representations in respect of the matter. Other key stakeholders may include e.g. the National Treasury and relevant provincial treasury, the national and provincial departments responsible for local government and the MEC for local government in the province. (p92-94, Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act, Act No. 56, 2003) 8.2.3 For the purposes of this section, “establish” includes the acquisition of an interest in a private company that would render that private company a municipal entity.” (p92-94, Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act, Act No. 56, 2003) 8 8.2.4 “… If a municipal entity experiences serious or persistent financial problems and the board of directors of the entity fails to act effectively, the parent municipality must either-(a) take appropriate steps in terms of its rights and powers over that entity, including its rights and powers in terms of any relevant service delivery or other agreement; (b) impose a financial recovery plan, which must meet the same criteria set out in section 142 for a municipal recovery plan; or (c) liquidate and disestablish the entity…” (p110, Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act, Act No. 56, 2003) 8.2.5 Municipalities are encouraged to take all steps necessary to convert non-compliance structures like section 21 companies, trusts and other forms (p13, Modernising Financial Governance, Implementing the Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 – Updated Version: August 2004 ) 9 9. Empirical Analysis In South Africa the SOEs are regulated by a number of broad policy frameworks and various pieces of legislation. Whilst the list of SOEs is made up of institutions that operate at national, provincial and local spheres of government, it continues to evolve. 9.1 Assumptions 9.1.1 Where possible, both objective and subjective data will be used in the exercise. 9.1.2 Other than PFMA, no central data repository and up to date list exists in respect of national, provincial and local SOEs that were either established or de-established in SA 9.2 National and Provincial SOEs 9.2.1 In a study conducted by KPMG on behalf of the PRC on SOEs, it is estimated that there are approximately 502 national and provincial SOEs (including subsidiaries) operating in South Africa. For further details, see the Governance & Ownership Workstream report on the Database. 9.2.2 Amongst others, the list of newly established and proposed SOEs includes the following viz. Broadband Infraco, State’s Mining Company, and proposed pharmaceutical firm. 9.2.3 De-established national and provincial public entities include e.g. Pebble Bed Modular Reactor etc. 9.2.4 The list of established and de-established national and provincial SOEs is not exhaustive, and this is mainly due to a lack of a central data repository on SOEs. 9.3 Local Government SOEs 9.3.1 In terms of Section 74 and 178 of the MFMA, municipalities are required to report to the National Treasury information on all municipal entities, including those structures in existence prior to the MFMA and MSA framework taking effect. (p1, Updated Municipal Entities Report, information obtained from Municipalities as at 30 June 2010, National Treasury) 9.2.2 As at 30 June 2010, there were 63 Municipal Entities. The largest concentration of municipal entities is in Gauteng (26), fifteen of which are controlled by the City of Johannesburg. The second largest number of municipal entities is located in the Eastern Cape (11) and KwaZuluNatal (9). The remaining balance straddles across the remaining six provinces. From the sixty three municipal entities, National Treasury was advised that five were in the process of being dis-established (i.e. Kouga Cultural Centre (Eastern Cape); Temba Roodeplaat Water Services Trust and Tshwane Centre for Business Information and Support (Gauteng); Govan Mbeki Housing Trust Company and Mbombela Development Trust (Mpumalanga)), while one entity is under review (i.e. Uthukela Water (KwaZulu-Natal). (p2, Updated Municipal Entities Report, information obtained from Municipalities as at 30 June 2010, National Treasury) 10 Graph 1: Municipal Entities per Province as at 30 June 2010 Northern Cape, Western Cape, 1 4 North-West, 2 Mpumalanga, 4 Eastern Cape, 11 Limpopo, 2 Free State, 4 KwaZuluNatal, 9 Gauteng, 26 Source: National Treasury 9.2.3 As at 30 June 2010, thirty four municipal entities were dis-established. Graph 2: Dis-established Municipal Entities Northern Cape, 1 North-West, 0 Mpumalang a, 0 Limpopo, 0 Western Cape, 2 Eastern Cape, 4 KwaZulu-Natal, 7 Gauteng, 19 Source: National Treasury 11 Free State, 1 9.2.4 The following chart depicts municipal entities by function. Graph 3: Municipal Entity Function as at 30 June 2010 Markets 2% Manufacturing 2% Tourism 11% Development & Planning 28% Housing 14% Finance & Administration 6% Transport Buses & Roads ElectricityMuseums & Services Art Galleries 5% 3% 2% Water 8% Public Safety 1% Solid Waste 2% Sewerage Community Other 5% Halls & Facilities 3% 8% Source: National Treasury In graph 3, it is interesting to note that circa twenty eight per cent of municipal entities are concentrated in the Development and Planning, and underweight in what could be classified as key service delivery by function. 9.2.5 All sixty three municipal entities per type are listed in the graph below. Graph 4: Municipal Entity Types as at 30 June 2010 Multijurisdictional Service Utility 2% Service Utility 11% Trust 9% Private Company 40% Section 21 Company 38% Source: National Treasury 12 Graph 4 seeks to confirm that approximately 13 per cent of municipal entities could be classified as service utilities. On the other hand, private companies and section 21 companies including trusts accounts for 87 per cent of municipal entities, per type. 9.1.5 Over the years, a number of SOEs have both been established and deestablished. 10. International Experience 10. 1 China 10.1.1 In March 1998, reform of the sick state sector moved to the top of the political agenda in China (Special Report: Business in China, The Economist) 10.1.2 The then prime minister, Mr. Zhu Rongji, enunciated the doctrine of zhu fangxiao (“grasp the big, let go the small”), which remains the guiding principle of SOE restructuring. It means that the government wants to keep control of the biggest and most important companies, but will let the smaller ones fend for themselves. (Mattlin, 2007) 10.1.3 The re-organization of the Chinese SOE sector i.e. restructuring, mergers and closures reduced the number of SOEs from circa 262,000 to 174,000 in 2001. (Special Report: Business in China, The Economist) 10.1.4 Stock market listings were encouraged, more especially, if these could bring in technology, private sector expertise and discipline. But the government intends to remain in control. 10.1.5 The founding of the State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) in 2003 under the State Council launched a process of redefining the relationship between central government and the so-called ‘central enterprises’ – the key SOEs that have been selected by the government to form the basis from which China’s future top global companies will be created. 10.1.6 SASAC at the national level handles the state’s ownership interests as well as regulation and supervision of central enterprises, while the Ministry of Finance retains overall responsibility for all state-owned enterprises as well as the financial matters of non-corporate entities, such as agencies. SASAC’s mandate does not cover financial organisations. (Mattlin, BICCS Asia Paper Vol. 4(6)) 10.1.7 One hundred and thirty six (136) central enterprises out of a total of 120,000 SOEs fall under SASAC. Central enterprises account for the bulk of SOE profits (circa 70%, equivalent to 20% of government revenues) and around a quarter of SOE corporate investment. (Mattlin, BICCS Asia Paper Vol. 4(6)) 10.1.8 The combined value of the assets of central enterprises amounted to circa 1.2 trillion Euros in 2006. (Mattlin, BICCS Asia Paper Vol. 4(6)) 10.1.9 SASACs stated objective is to reduce the number of central enterprise from 140 to circa 30 to 50 globally competitive companies. Hence, where 13 possible, mergers are encouraged to achieve a scale at which they can compete globally. 10.2 Norway 10.2.1 State capitalism exists and encouraged in Norway. 10.2.2 “… The State ownership must have a dynamic approach to its ownership, so that the instruments that are used are at all times appropriate for the goals behind the State’s ownership. The proportion of a company that the State should own is linked to the question whether State ownership is an appropriate instrument for achieving relevant social objectives and bringing about the growth of the company, as well as the sector in which it operates and structural considerations…” (p38, Meld. St.13(2010-2011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) 10.2.3 As a prerequisite clear goals must be established for State’s involvement 10.2.4 The four categories that form the basis for State ownership in the various companies are viz. (a) companies with commercial objectives (Category 1); (b) companies with commercial objectives and national anchoring of their head office functions (Category 2); (c) companies with commercial and specifically defined objectives (Category 3); and (d) companies with sectoral policy objectives (Category 4). 10.2.5 In the case of companies with commercial objectives (Category 1), the State’s objective is commercial profitability, high level of value creation, and highest possible return on investment over time. The State’s interest may vary if they would help promote the country’s industrial and commercial development and safeguard the State’s interest. (p44, Meld. St.13(20102011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) 10.2.6 The State’s ownership in Category 2 of companies is motivated by commercial interests, but with added dimension that national anchoring of the company’s office in Norway facilitates research, innovation and technological development. National anchoring is ensured through a shareholding of more than one third. “… The State’s shareholding in Category 2 shall remain unchanged, unless it is considered appropriate to adjust the shareholding in extraordinary circumstances. Examples of such circumstances may include a merger or a share issue in order to facilitate international growth through an international acquisition for example…” (p44, Meld. St.13(2010-2011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) 10.2.7 For companies with commercial and other specifically defined objectives, the State’s shareholding will remain unchanged. The shareholding may be considered appropriate to adjust in cases where ownership is replaced with regulatory measures as an instrument. For example, this may apply to companies, “… where the aim of the ownership is to monitor the sustained production of products and services of importance to national security or to safeguard national sovereignty. The same applies where the State ownership is to safeguard the national ownership of natural resources and a desire to correct the failure of the capital markets through 14 contributing to competition, capital, etc. …” (p45, Meld. St.13(2010-2011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) 10.2.8 The State’s shareholding in Category 4 companies primarily has sectoral objectives.”… The State’s shareholdings in the companies in Category 4 shall remain unchanged, unless it is considered appropriate to adjust the shareholding in extraordinary circumstances. In practice, such circumstances will rarely arise…” (p45, Meld. St.13(2010-2011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) 11. Key Findings The findings of our empirical exercise could be summarised as follows: 11.1 That despite its limitations, a policy framework for the establishment and de-establishment of SOEs at national, provincial and local spheres of government exists. International experience seeks to confirm that a policy for establishment and de-establishment of SOEs should be derived from the basis for State’s ownership in the various companies e.g. Norway 11.2 The accounting officer for a public entity that is not listed in either Schedule 2 or 3 must, without delay, notify the National Treasury, in writing, that the public entity is not listed. However, this does not apply to an unlisted public entity that is a subsidiary of a public entity, whether the latter is listed or not. 11.3 Approximately 13 per cent of municipal entities could be classified as service utilities. On the other hand, private companies and section 21 companies including trusts accounts for 87 per cent of municipal entities, per type. This is despite Municipalities having been encouraged to take all the necessary steps to convert non-compliance structures like section 21 companies, trusts and other forms. 11.4 Twenty eight per cent of municipal entities are concentrated in the Development and Planning, and underweight in what could be classified as key service delivery by function. Hence, municipal service delivery strikes in various parts of SA. 12. Recommendations 12.1 That the South African government should, as a prerequisite, clearly establish and articulate its goals for State involvement in the economy. 12.2 That the PFMA should be amended so that the listing of SOE subsidiaries, i.e. Schedule 2 and 3 SOEs, becomes compulsory. 12.3 Both the MFMA and Municipal Systems Acts should be amended in order to avert the creation and proliferation of non-compliance structures e.g. section 21 companies, trusts and other forms 15 13. Reference List Basu P (2008) Reinventing Public Enterprises and Their Management as the Engine of Development and Growth in Public Enterprises: Unresolved Challenges and New Opportunities, United Nations Publication Department of Public Service and Administration and National Treasury (2002), Interim Guide for Creating Public Entities at the National Sphere of Government IMF (1995), Bureaucrats in Business, The Economics and Politics of Government Ownership Local Government Municipal Systems Act (Act No. 32 of 2000) Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act, Act No. 56, 2003) Mattlin M (2007) The Chinese Government’s New Approach to Ownership and Financial Control of Strategic State-Owned Enterprises Mattlin M, (Updated) BICCS Asia Paper Vol. 4(6)) National Treasury (Updated Version: August 2004) Modernising Governance, Implementing the Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 Financial National Treasury (2010), Updated Municipal Entities Report, information obtained from Municipalities as at 30 June 2010 Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry (2010) Meld. St.13 (2010-2011) Report to the Storting (White Paper) Summary, Active Ownership) – Norwegian State ownership in a global economy Public Finance Management Act (Act No. 1 of 1999) The Economist (2011) Special Report: Business in China – China’s state-owned enterprises want to make their mark on the world stage 16