a quantitative analysis based on census data, 1900-70

advertisement

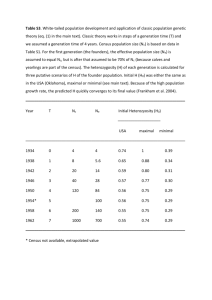

The work of Spanish older men: a quantitative analysis based on census data, 190070 Alexander Elu Terán, University of Barcelona I. Introduction The management of the last years in people’s lives is a delicate issue involving economic, social and psychological factors. Historically, this phase was spent within the shelter of intergenerational solidarity, that is far from the harshness of public relief schemes. The extreme character of this last option points actually at the most common way old age was faced, particularly before legal retirement existed. This was to remain in the labour force, often at any price and accepting unpleasant changes. Therefore, we understand that the study of the economics of old age needs to be founded on labour markets. This line of research has already been addressed in a number of works which linked a historical approach with current concern on ageing. More specifically, our paper intends to exploit the quantitative perspective allowed by national population census and, particularly, their ageprofession tables1. Our purpose will be to test for the existence of a specific problem in the market for older workers, basically consisting on the narrowing of available jobs as a result of a life-cycle deskilling process, according to which old workers are pushed towards low-paid and low-skilled jobs. This paper is structured in two sections. First, the quantitative importance of work at old age will be addressed in aggregate and comparative terms. Then, we will want to know whether those participation rates were characterized by the life-cycle deskilling factor. After the examination of alternative explanations, the logic of the pattern will be discussed and some conclusions will be given. II. Aggregate reconstruction of work at old age through the census Decennal population census since 1900 are adequate sources for analyzing the age structure of professional classifications in the long-term. Despite prevention against their accuracy must be preserved 2, the main trouble with Spanish census is an annoying heterogeneity with professional definitions and age intervals. With respect to the latter, two major distortions are to blame. The first one has to do with the impossibility to exploit the 1950 census, as age groups appear on a decennal basis starting from 25 years of age. Thus, it is not feasible to unify the 1950 data with that of the remaining census, which all show ten-year-wide age brackets starting at the beginning of the decade. Secondly, no age-profession table exists for the 1960 census record. Lastly, we also faced the poor definition of age brackets in 1920 [21-60, +60] and heterogeneity arising from the 1900 and 1910 census, with 20-year-wide age intervals. To avoid an extreme simplification of the table in favour of homogeneity, we note the cases when actual age groups do not exactly match those in the matrix. 1 2 RANSOM, SUTCH (1986, 1988); JOHNSON (1994). Also LEE (2002). We restricted to male employment to avoid some of those inaccuracies. As seen in figure 1, participation rates among older males were quite high along the period. We can only appreciate a slight decline in 1920 with respect to earlier cuts. Participation rises again for 1930, but not at 50-59. As expected, we see a fall in the 20-29 group in 1970. This behaviour very likely responds to more general access to high education. Concentrating now on the participation of workers aged 60 and more, the table shows both high and stable participation until a strong decline is perceived for 1970. Indeed, the 19401970 gap is wide enough so as to make it a really steep fall. Indicatively, older workers’ participation in 1950 was 66,06%, although it is referred to men 65. However, the decreasing trend on the matrix hides some important changes occuring through such a wide time-span. For instance, we should have accounted for the changing demography of males aged 60 and more to correct for the upward bias in the first censuses, given the declining propension to work with age. Unfortunately, this is not feasible with our data. On the other hand, we enjoy more possibilities if we want to control for changes in the production structure of the Spanish economy. Such an exercice should capture the different patterns of retirement among different professional sectors. In this sense, there is evidence on lower retirement rates in agriculture, so structural change should be a powerful factor in the fall of participation among oldest workers3. In order to establish such comparison, we proceeded as follows. First, we applied the rates of agricultural and non-agricultural labour for 1970 (26,53%; 73,47%) to the sum of working population registrated in each previous census. Second, these virtual figures of agricultural and non-agricutural workers were applied to the actual rates of male population below and above 60 occupied in each of the two sectors. As a result, we obtain participation rates of older men for each census according to the bivariant sectoral distribution of 1970. The natural extension to this exercice is to control for all sectoral changes produced in the economy. So, we have applied participations for each one of the 1970 sectors to each of the earlier census. This imputation has been made according to the 29 professional groups through which censual classifications were uniformed -and presented in figure 54-. With such adjustments, we will want to capture changing attitudes towards retirement accross sectors. LEE (2002). The exercise becomes especially relevant for the traditional Spanish economy, where agriculture –farming included– employed in 1900 63,29% of male workers. In 1910, 59,79%; 62,07% (1920); 49,99% (1930); 54,82% (1940); 51,95% (1950); 26,53% (1970). 4 For 1970 we miss some previously recorded classifications, so we had to aggregate as follows: alcohol, wine and tobacco were added to food industries; fur, and dress and shoe industries to textiles; storage to transport; professionals, clergy, army and labourers to others. 3 Source: own elaboration *65 According to the numbers in figure 2, sectoral shift in the Spanish economy was a remarkable force behind the decline in participation of older men. Yet, this impulse mainly corresponds to agriculture decline, given the very similar rates for agriculture-adjusted and all-sector-adjusted. However, discrepancy between these two magnitudes in 1940 and, above all, 1920 suggests that the service sector offered then better occupational opportunities for eldest workers. In general, Spanish figures regarding participation rates of older men are quite high, particularly with respect to other national cases (figure 3). III. The work of older males from a sectorial perspective So far, the work of older men has been addressed on aggregate basis. However, we need to descend to a more specific level to detect problems operating in this segment of the market. As announced, we will test whether the life-cycle deskilling hypothesis also applies for the Spanish case. For that, we need a measure of sectorial overrepresentation of older workers. We proceeded as follows. First, a sectorial grouping of all professional categories on the census has been made controlling for an accurate uniforming of changing definitions throughout census. Then, a ratio of occupational concentration was calculated to detect sectors in which older workers were over or underrrepresented. On the numerator, we placed the percentage of the workforce aged 60 and more employed in a given sector. On the denominator, we put the percentage of the total workforce, irrespective of ages, employed in that same sector. So, a ratio equal to 1 would point at a full correspondence between the percentage of older men employed in a sector and the percentage of the total workforce employed in the same occupation. So, indexes above unity will screen overrepresentation cases focusing our interest. As we see in figure 5, overrepresentation of eldest workers takes place more prominently in agriculture. The result is consistent with the assumed sector’s higher probability of retaining workers in the labour force, assuming the sector’s flexibility to adapt to the need for shorter, less intense and, in general, more flexible work-days desired at old age. Other sectors where overconcentration takes place are domestic service (27), or food services (23), both fitting the life-cycle deskilling pattern sketched in our hypothesis: low wages, minimal qualification requirements, etc. Inversely, underrepresentation is stronger in leading, technologydriven sectors. So far, our results are consistent with those of previous works. However, our numbers differ in the sense that they also support the inverse pattern of concentration on some ‘better’ sectors such as professionals (21; 1910, 1920) or administration. For these other cases, we should infer the retaining of experience-related abilities and skills. Such two-sided pattern actually accentuates when the heavy weight of agriculture is ruled out from our calculations. As a result, eldest workers persist in some of the more-attractive, better-paid sectors but overconcentration now also appears in textiles (7), tobacco (6), alcohol and wine (5) or even fishing (2). In conclusion, the life-cycle deskilling theory applies fairly well for Spain, despite overrepresentation in some high sectors. IV. Alternative hypothesis Results discussed so far may not only respond to the working of the ‘life-cycle deskilling’ process, as some other factors must be discarded before accepting our hypothesis. First, the ageing of an industry might result from changes in the size of sectors. This means that ageing in one sector would account for its contraction. The way to evaluate the incidence of this is the calculation of Spearman’s rank-order correlation between the percentage growth of occupied workers in each sector between census and the concentration index of eldest workers. If a sufficiently negative correlation between both magnitudes is confirmed, we will reject the null hypothesis of no correlation and so accept the influence of sectorial decline on age structures. Our contrasts do not support the alternative hypothesis for most periods for which the exercise was made, that is 1900-1970 and also each of the intercensal years. Exceptions are 1930-1940 and 1940-1950. In the first of these cases, the statistic -0.50 makes us accept the alternative hypothesis (Spearman’s rho is -0.392, n=26, 5% significance)5. For 1940-50, the statistic -0.5733 yields the same result (n=26). Both cases actually correspond to periods affected by serious contamination. On one hand, the sole testing of the 1940-1950 period is arguable, as it mixes figures corresponding to workers aged 60 with those in the 1950 census, that is 65. On the other hand, the 1930-1940 result is affected by the shock and consequences of the Civil War. So, we can safely state that changes in size are not a plausible explanation for our indexes. A second alternative reason deals with possible differential mortality rates among sectors. According to this, lower mortality in some sectors causes excess concentration of older workers. This hypothesis is not easy to test, as we miss records of professional mortality for Spain. A traditionally applied proxy has been differential mortality between town and country. In this case, results supported the existence of a clear differential in favour of rural contexts for Great Britain, France or the US during the second half of the nineteenth century. However, it was also suggested that the urban penalty disappeared, if not reversed, during the first decades of the twentieth century6. Spanish data would support this argument. Thus, from an unfavourable position in town during the nineteenth century, a progressive smoothing of mortality differentials took place until, after the Civil War, the trend reversed7. But even before, for 1900-1930, REHER identified how ‘the fall in mortality in the countryside was always higher than in the city, except for an age group (60-69)’8. Therefore, it appears that old-age concentration on the agricultural sector seems to be related to more than mortality differentials. In fact, we believe that the eventual analysis of occupational mortality figures could both support significant mortality differentials, but also the existence of a lyfe-cycle deskilling dynamic. In this sense, it seems reasonable that more severe physical strain in some occupations, if manifested gradually, drove to less physically-demanding jobs within one sector and to other sectors as well 9. Actually, the push factor in this case would be morbility or loss of abilities annnouncing an earlier death. 5 Observations in this pair are actually 27. As there is no critical value tabulated for this n, n=26 was taken. In all cases, one-tailed tests. 6 HAINES (1991), p. 181; WRIGLEY et al. (1997), pp. 201-206. 7 REHER (1998), p. 66-67. 8 Ibidem, p. 80 9 HAINES (1991), p. 179, RANSOM, SUTCH (1986), p. 26. V. Conclusions As we saw, some elements advice a still careful relating of our occupational concentration indexes with the life-cycle deskilling phenomenon. Yet, our results provide some robust evidence on the gradual expulsion of Spanish workers towards less attractive sectors as they get old. Reasons behind such horizontal segmentation are several. From the demand side, it is quite sure that employers performed an effective discrimination against eldest workers. The perception of a decline in abilities made oldest employees more eligible for jobs with lower ability needs, lower training requirements or less responsibility. There are two fundamental causes for this discrimination. First, educational progress among cohorts and, second, technological change, which per se complicates the adaptation of any worker. In fact, even if technological change led to the requalification of a worker, the costs of this process applied to older workers do not usually compensate the present value of associated benefits 10. From the supply side, workers’ preferences may also act in the deskilling process. With respect to this, inflexibility associated with team work or the submission to mechanisation proceedings associated to high productivity may provoke an exit to more adaptable sectors. At the same time, the specificity of lifetime human capital acquired in a single job forces work continuation in a different sector 11. Thus, a greater demand of low-skilled labour or the rise in service activities –as assumed to be more flexible– would in theory favour the work prospects of older workers12. The observed increase of self-occupation at older ages actually fits this pattern13. Lastly, the overcoming of the gain peak around 40-50 years would also incentivate the withdrawal from more profitable, but also more demanding jobs as a way to increase leisure once the fall in pay starts14. VI. References -COSTA, Dora L. (1998): The evolution of retirement: an American economic history, 1880-1990, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. -HAINES, Michael R. (1991): ‘Conditions of work and the decline of mortality’, in SCHOFIELD, R.; REHER, D.; BIDEAU, A. (eds.): The decline of mortality in Europe, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 177-195 -HURD, Michael D. (1996): ‘The effect of labor market rigidities on the labor force behavior of older workers’, in WISE, D.A. (ed.) (1996): Advances in the economics of aging, NBER-The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 11-58. -JACOBS, Klaus; KOHLI, Martin; REIN, Martin (1991a): ‘The evolution of early exit: A comparative analysis of labor force participation patterns’, in KOHLI, M.; GUILLEMARD, A-M.; Van GUNSTEREN, H. (eds.) (1991): Time for Retirement. Comparative Studies of Early Exit from the Labor Force, Cambridge UP, pp. 37-66. -____________ (1991b): ‘Testing the industry-mix hypothesis of early exit’, in KOHLI, M.; GUILLEMARD, AM.; Van GUNSTEREN, H. (eds.) (1991): Time for Retirement. Comparative Studies of Early Exit from the Labor Force, Cambridge UP, pp. 67-96. -JOHNSON, Paul (1994): ‘The employment and retirement of older men in England and Wales, 1881-1981’, Economic History Review, XLVII, I, pp. 106-128. -JOHNSON, Paul; ZIMMERMANN, Klaus F. (1993): Labour Markets in an Ageing Europe, Cambridge UP, Cambridge. -LEE, Chulhee (2002): ‘Sectoral shift and the labor-force participation of older males in the United States, 1880-1940’, Journal of Economic History, vol. 62, 2, pp. 512-523. -MITCHELL, B.R. (ed.) (2003a): International Historical Statistics. The Americas 1750-2000, PalgraveMacMillan, New York. -___________________ (2003b): International Historical Statistics. Europe 1750-2000, Palgrave-MacMillan, New York. -RANSOM, R.; SUTCH, R. (1986): ‘The labor of older Americans: retirement of men on and off the job, 18701937’, Journal of Economic History, vol. 46, 1, March, pp. 1-30. -____________________ (1988): ‘The decline of retirement and the rise of efficiency wages: U.S. retirement patterns, 1870-1940’, in RICARDO-CAMPBELL, R.; LAZEAR, E. (eds.): Issues in contemporary retirement, Hoover Institution, Stanford, pp. 3-37. -REHER, David S. (1998): ‘Mortalidad rural y mortalidad urbana: un paseo por la transición demográfica en España’, in DOPICO, F.; REHER, D.S.: El declive de la mortalidad en España 1860-1930, Asociación de Demografía Histórica, monografía núm. 1, pp. 59-103 -WISE, David A. (1993): ‘Form Pension Policy and Early retirement’, in ATKINSON, A.B.; REIN, Martin (eds.): Age, work and social security, St. Martin’s Press, New York. -WRIGLEY, E.A.; DAVIES, R.S., OEPPEN, J.E.; SCHOFIELD, R.S. (1997): English population history from family reconstitution, 1580-1837, Cambridge UP, Cambridge. 10 COSTA (1998), p. 24 on education; J ACOBS et al. (1991b), p. 68 on technology. HURD (1996), p. 13. 12 RANSOM, SUTCH (1986), p. 19. 13 JOHNSON, ZIMMERMANN (1993), p. 56 14 WISE (1993), pp. 51-52 11