Syntax and Grammar of Trade

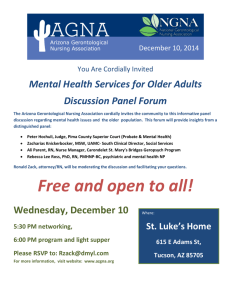

advertisement