Communist Yugoslavia`s expulsion from the Soviet Union`s Eastern

advertisement

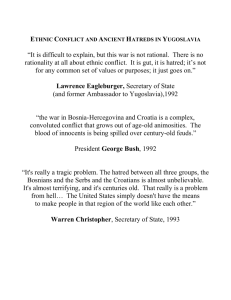

DRAFT COPY: NOT FOR QUOTATION OR CITATION WITHOUT THE AUTHOR’S PERMISSION Building Tito-Land: America’s Cold War Fantasy By Louie Milojevic Reducing adversaries and complex international challenges to simplified proportions has been a hallmark of U.S. foreign policy; so observed the insightful Gabriel Almond in his classic study, The American People and Foreign Policy.1 Nowhere was this American tendency more apparent and misguiding than in the period Almond was writing, the early Cold War. President Harry Truman and Winston Churchill had by this time notified the American public that an “iron curtain” had divided the continent of Europe into two ways of life: one “based upon the will of the majority,” and another “based upon the will of a minority forcibly imposed upon the majority.”2 Truman and Churchill, however, had not been informed that the world they spoke of was in fact divided into three parts – East, West, and Yugoslavia.3 Communist Yugoslavia’s expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau on June 28th 1948 signified the emergence of an early Cold War middle ground that defied conventional understanding and management.4 Never before, reported the State Department, had the international community encountered a communist state that rested on the basis of Soviet ideology and organizational principles, and yet remained 1 Gabriel Almond, The American People and Foreign Policy (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1950), 56-57. While this tendency is more characteristic of the uninformed general run of the population, it affects policymakers as well. Thus, during World War II, the Roosevelt shift from “Dr. New Deal” to “Dr. Win the War” reflected the need at the highest level to reduce issues to simplified proportions. 2 Special Message to Congress on Greece and Turkey: The Truman Doctrine, 12 March 1947. 3 Alexander Werth, “Yugoslavia: Neither East Nor West,” The Nation, 27 November, 1948. 4 For a recent explanation of the causes of the Soviet-Yugoslav split see Jeronim Perovic, “The Tito-Stalin Split: A Reassessment in Light of New Evidence,” Journal of Cold War Studies 9 (Spring 2007): 32-62. Perovic contests the established school of thought that Moscow’s concerns about Yugoslavia were primarily ideological. He argues that recently declassified documents indicate Stalin was mainly concerned about Tito’s “unsanctioned” pursuit of an expansionist foreign policy agenda toward such neighbors as Albania 2 independent of Moscow.5 Time magazine’s editorial was apt as well, reporting that the diplomatic rupture between Moscow and Belgrade was the “weirdest political show on earth, a Cold War between two communist police states,” but also a “tremendous opportunity” and “serious problem” for U.S. policymakers.6 How Cold War America reacted to, understood, and ultimately formulated a policy response to this development is the focus of this study. The following analysis departs from the orthodox interpretation of early Cold War U.S.-Yugoslav relations; it views the initiation and extension of aid to Tito’s Yugoslavia not merely as an exercise of strategic convenience, but also as a public and cultural encounter which confused, fascinated, and divided mainstream America. Specifically, this study contends that U.S. policymakers, journalists, and citizens struggled to uniformly come to terms with the third option that Cold War Yugoslavia claimed to represent. In shaping and sustaining an aid program, this study contends as well that advocates and opponents of U.S. assistance publicly reinvented Tito’s Yugoslavia in terms that were familiar to Americans. Eager to make sense of the ‘Yugoslav option” they were about to invest in, Cold War Americans focused their attention on Yugoslavia’s enigmatic communist dictator, Josip Broz Tito; he was at once a repulsive and appealing figure, a potential ally against the Soviet Union, and an adversary of democracy. Washington’s growing anticommunist track-record, however, suggested this was insufficient progress to warrant the pursuit of deeper U.S.-Yugoslav relations. As Lorraine Lees notes, White House officials became household names by predicting the eventual triumph of America’s belief system PPS/35, “The Attitude of this Government Toward Events in Yugoslavia,” 30 June 1948, FRUS, 1948, vol.4, 1093. 6 Editorial, “The Great Schism,” Time, 18 April, 1949. 5 3 over that of the Soviet communist adversary.7 Ties with Tito’s regime, a regime that in every measure resembled Josef Stalin’s, could amount to sanctioning the international proliferation of miniature independent Moscow-type regimes; although damaging to the structure of the Soviet satellite system, this would be difficult to ask of American tax payers, and even more difficult to sustain as an actual policy. At the same time, American observers could not help but be captivated and impressed by Yugoslavia’s exceptional circumstances. The unfolding story of Yugoslavia’s independence and survival outside of the Soviet-bloc in a short time developed several quintessential American qualities. Yugoslavia was not simply expelled from the Soviet-bloc to implode from within and return a Moscow satellite; the Yugoslavs were also ganged-up on, isolated, and being intimidated into submission, by the full weight of Soviet economic sanctions and aggressive border posturing. It was not uncommon for American newsmen to report that: The difficulties facing Tito are as daunting as can be, so daunting that only the toughest of peoples, cocksure to the point of arrogance, could face with any confidence. But the Yugoslavs are the toughest peoples, cocksure beyond the point of arrogance. They have a faith in their essential superiority which has no evident justification but which is perhaps redeemed by their unsurpassed courage. It was this faith which got them into their present extraordinary position, a position theoretically untenable, which they yet continue to sustain.8 This outnumbered-surrounded and against all odds perspective was the theme of choice for many newspapers, as they sought to convey the Yugoslav plight in terms that were familiar to Cold War Americans. Yet this tendency also demonstrated the print media’s capacity to engage in the public re-invention of a regime whose brutality was identical to that of the Soviet Union. Coming to terms with Tito’s Yugoslavia would therefore prove 7 Lorraine M. Lees, Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), xv. 8 Edward Crankshaw, “Tito’s Dilemma: His Link With the West,” New York Times, 15 January, 1950. 4 to be as critical an inward-looking moment for U.S. foreign policy as any in the struggle against Soviet communism. The liberation of Soviet controlled Eastern Europe was one phase of this struggle where American policymakers were hopeful but realistic, setting low short-term expectations. Military considerations and the risk of a wider war were the primary impediments to an effective rollback of communism; but Washington insiders also knew that not all of the “ancient states” behind the “iron curtain” had a desire to join the western democracies.9 Yugoslavia, for instance, was widely recognized as an indigenous communist regime, subservient to nobody, but nevertheless loyal to Moscow.10 In the early Cold War, the regime in Belgrade distinguished itself as the most assertive in Eastern Europe; it enforced its airspace with lethal force, interfered in Albanian politics, supplied communist insurgents in Greece, and directly threatened Western defenses in Italy.11 However, that Tito was by Soviet standards overplaying his role in international affairs never crossed the minds of officials in Washington.12 Nor did they ever expect Tito’s communist regime to produce the crack in the Soviet-Bloc they so eagerly sought. Moscow’s decision to sever ties with Belgrade the same week it barricaded Berlin compelled Washington insiders to contemplate Yugoslavia’s new independence in strictly short-range geo-strategic terms. Yugoslavia’s geographic significance, military strength, and wartime reputation for combat effectiveness were emphasized frequently in In Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech Yugoslavia is included in the list of “ancient states” that were forced behind the iron curtain. Yet, it was the Prime Minister’s wartime recommendation to shift allied support from the Monarchists to Tito’s Partisans that most contributed to the success of Yugoslavia’s communists. 10 Policymakers and scholars alike remembered that the Yugoslavian Communist Party was not like those which the Soviet Union put in power in neighboring Hungary or Bulgaria. The communists in Belgrade came to power through a wartime resistance movement and revolution which had roots in Yugoslav soil. 11 Yugoslavia contested Italy’s rights to the city of Trieste until 1954. 12 Perovic, 34. 9 5 official communications. Policymakers concurred that a genuine break between Moscow and Belgrade would have little downside in the event of a future European conflict. At the very least, an independent Yugoslavia would relieve pressure off of the Greek and Italian borders by removing its army of thirty-three divisions, the largest in Eastern Europe, from the Soviet arsenal and remaining neutral. In ideal circumstances, those same thirty-three divisions would engage Soviet forces before they gained enough momentum to overwhelm Western defenses in Greece and Italy.13 As compelling as these geo-strategic grounds for aiding an independent communist state in the underbelly of Europe were, they were only as compelling as the deep ideological line that public officials had drawn between communism and democracy. It was hardly debatable on which side of this line Yugoslavia belonged. Even after the break with Moscow, Tito regularly reminded international observers of Belgrade’s continued commitment to communism.14 Given the contradictions involved in a democratic state assisting a communist one in order to achieve an eventual end to communism, the decision to aid Tito would therefore not be made without considerable public scrutiny. Nor would such a policy be sustained in a singular or unifying national voice. By 1948, Americans in and out of government had become fixated with the ideological stakes in the emerging global Cold War. They accepted and expected that the choice facing them and every nation was between two opposing and irreconcilable ways of life. Communism was widely perceived as being distasteful and threatening; so much John C. Campbell, Tito’s Separate Road: America and Yugoslavia in World Politics (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), 19. See also Beatrice Heuser, Western Containment Policies in the Cold War: The Yugoslav Case, 1948-1953 (New York: Routledge, 1989), 112-125. Yugoslavia had 325,000 men under arms. 14 Andre Laguerre, “A Search for Laughter,” Time, 30 January, 1950. 13 6 so, that anti-communism helped Americans make sense of a complex and unfamiliar world – and of the rapid changes underway in their own country as well.15 The appearance of Yugoslavia as an independent but still communist state on the international stage, however, raised the possibility that not all communists were as menacing as the Soviets. Additionally, it suggested that America could perhaps co-exist with, support, and promote strategically an independent brand of national communism. Cold War scholars have for quite some time recognized this Yugoslav communist exception as a critical component of America’s containment strategy. In The Long Peace, John Lewis Gaddis finds that the survival of Tito’s Yugoslavia offered U.S. strategists more than immediate geo-strategic benefits in a volatile Europe. Gaddis considers Yugoslavia the centerpiece of a Truman and Eisenhower administration “wedge” strategy, which had as its main objective the long-term disintegration of the Soviet-Bloc.16 Based on the belief that Western economic aid could influence relations within and among communist states, the strategy sought to “keep Tito strong” and fiscally “afloat” long enough to legitimize a Yugoslav national communist alternative in Eastern Europe and also Asia.17 Despite these calculations, Cold War scholars have neglected to consider the full array of complexities involved in developing a long-term U.S.-Yugoslav relationship. The studies that have focused on this area have been few and far between, and generally Fredrik Logevall, “A Critique of Containment,” Stuart L. Bernath Memorial Lecture, 27 March 2004. John Lewis Gaddis, The Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 152-194. 17 Dean Acheson to Cavendish Cannon, 25 February, 1949, FRUS, 1949, 5: 873-875. See also Marc Selverstone, Constructing the Monolith: The United States, Great Britain, and International Communism, 1945-1950 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 116-145; David Allan Mayers, Cracking the Monolith: U.S. Policy against the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1949-1955 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986). 15 16 7 consistent in method and conclusion.18 Preferring a top-down and behind the scenes approach, U.S.-Yugoslav specialists have with the aid of steady declassification developed a comprehensive decision-maker’s record of the implementation of the wedge strategy. In the most recent contribution to this record, Lorraine M. Lees details the development of a decade-long U.S.-Yugoslav aid relationship that is staggering in scope and scale. The $1.5 billion in mostly unconditional economic and military aid Tito received between 1948 and 1958 was indicative of the gravity of Yugoslavia’s isolation and the seriousness with which U.S. officials pursued the wedge strategy. 19 However, absent from this approach has been the critical recognition that Cold War America was not only deciding whether or not to do business with Tito’s Yugoslavia, it was also engaging on a personal level this unique communist state which at once rejected Soviet domination and Western democracy. Aiding Tito was never a clear-cut executive decision. Nor was it a series of informal measures. Rather, it was a public phenomenon, which was imagined, contested, shaped, and re-shaped in the American Congress, print media, and town halls where opinionated Cold War Americans were certain to express their views. The policy of supporting a communist state in the service of an anti-communist foreign policy undermined too many articles of faith in the Cold War to remain solely a White House project. As Gabriel Almond has argued, “when foreign policy questions assume the aspect of an immediate threat to the normal conduct of affairs, they break into the focus 18 See Lorraine M. Lees, Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997); David L. Larson, United States Foreign Policy Toward Yugoslavia, 1943-1963 (Washington D.C.: University Press of America, 1979); John C. Campbell, Tito’s Separate Road: America and Yugoslavia in World Politics (New York: Harper & Row, 1967). 19 Lees, 227. This aid figure is found in NSC 5805 – the Eisenhower administration’s last full review of its Yugoslav policy. 8 of attention and share the public consciousness with private concerns.”20 Indeed, economic and military aid to Tito was officially billed a national security measure. However, it was the potential threat to America’s Cold War conscience this aid program presented that provoked what Almond has called the “public mood” and placed Tito’s Yugoslavia at the center of a probing and intense national debate.21 Amid the political confusion and bewildering variety of moods that characterized the initial debate to aid Tito, and the debates to continue aiding him beyond Stalin’s death to 1958, resides the intriguing but never fully certain American vision of Tito’s Yugoslavia. Allies and Enemies: The Two Faces of Yugoslavia, 1943-1948 The early Cold War policy of aiding Tito was not entirely unfamiliar ground for the United States. President Roosevelt’s wartime administration struggled with a Tito policy as well. In 1943, British officials persuaded the administration to expand U.S. assistance among the rival resistance groups in Nazi occupied Yugoslavia. Specifically, this meant extending U.S. support to Tito’s Communist-Partisans and elevating them to the status of allies.22 These measures, however, revealed as much about America’s ideological discomfort with Tito as they did the nation’s wartime aims. Roosevelt’s agreement to assist Tito’s Partisans was significant because it divided resources that would otherwise have gone to the United States’ original Yugoslav ally, General Draza Mihajlovic’s Royalist Chetniks. Redistributing aid to Tito signified an 20 Almond, 70-71. According to Almond, the reaction of the general population to foreign policy issues is one of “mood.” A mood, he argues, is essentially an unstable phenomenon. But this instability is not arbitrary and unpredictable. It is affected by two variables: (1) changes in the domestic and foreign political-economic situation involving the presence or absence of threat in varying degrees, and (2) the characterological predispositions of the population. 22 Lees, 2. See also Walter R. Roberts, Tito, Mihajlovic, and the Allies, 1941-1945 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1973). British officials had received unconfirmed reports that the Royalists were collaborating with the Nazis. By aiding Tito they hoped to gain influence with whatever government emerged in postwar Yugoslavia. 21 9 American commitment to hastening the defeating of the Nazis, but it did not represent a natural or formal alliance. That honor was extended to the Royal Yugoslav GovernmentIn-Exile in 1942, and maintained by Roosevelt even as he allowed Tito’s Partisans into the allied fold.23 Roosevelt was not pursuing any firm Balkan policy that was in place in Washington; rather, his relationship with the Royal Government was based on mutual respect, common principles, and a shared wartime experience. The Royal Government followed America’s lead and distinguished itself as an early signatory to the Atlantic Charter and Declaration of the United Nations. However, it was the performance of its resistance movement on the ground in Yugoslavia that won it the admiration of the American people, in a way Tito’s wartime resistance movement never did. According to a May 1942 Time magazine cover story, the Roosevelt administration had invested wisely in its aid to the Royalist Chetniks. The article reported that General Mihajlovic’s Chetniks had launched the “greatest guerilla operation in history,” causing such destruction that the Nazis had to declare a new state of war in their conquered territory. Comparing the General to an eagle watching “from the mountain walls and falling like a thunderbolt” on Nazi occupiers, the article credited him with the uniquely American feat of “preserving an island of freedom” and inspiring “the unknown thousands of supposedly conquered Europeans who still resist oppression.”24 This positive media coverage coincided with an official visit to Washington by King Peter and several members of his Government-In-Exile. The King was invited to speak before a joint session of Congress, but the high point of the visit came in a White House statement that demonstrated the fellowship between the two governments: 23 24 Roberts, 152, 167, 170, 172. Editorial, “The Eagle of Yugoslavia,” Time, 23 May, 1942. 10 We are in complete accord on the fundamental principle that all the resources of the two nations should be devoted to the vigorous persecution of the war. Just as the fine achievements of General Mihajlovic and his daring men furnish an example of spontaneous and unselfish will to victory, our common effort shall seek every means to defeat the enemies of all free nations.25 That same summer, Twentieth Century Fox began producing what would become Chetniks – The Fighting Guerillas, a major Hollywood motion picture portraying the General and his resistance movement as committed allies of the United States.26 By the time the movie was released in early 1943, however, the British Secret Service had managed to persuade the Roosevelt administration, on the basis of what Michael Lees has discovered to be faulty information that Mihajlovic was collaborating with Nazi forces.27 Although these allegations led to the critical redistribution of aid to Tito’s Partisans, Roosevelt continued to recognize King Peter as Yugoslavia’s ruler, and wartime Americans continued to publicly support the embattled General Mihajlovic. Support for the General would in fact outlive the monarchist Yugoslavia he built his reputation defending. As Lorraine Lees notes, upon learning that Mihajlovic had been captured and was to be tried for treason by the governing Partisans in March 1946, prominent Americans such as George Creel, Ray Brock, Sumner Wells, John Dewey, Norman Thomas, Clare Booth Luce, and Senators Robert Lafollette and Robert Taft formed a “Committee for a Fair and Free Trial for Draza Mihajlovic.”28 25 U.S. Department of State, Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 158 (July 25, 1942), 647. The movie was reviewed by the New York Times on March 19 1943. Reviewer Thomas M. Pryor observed the movie was “splendidly acted” and that it had “the right spirit.” 27 See Michael Lees, The Rape of Serbia: The British Role in Tito’s Grab for Power, 1943-1944 (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990) In what is a revisionist account of the civil war in Yugoslavia at the end of World War II, Lees discovers that Tito deceived the British Secret Service into believing Mihajlovic was collaborating with the Nazis. His research casts serious doubt on such works as Walter Roberts’s Tito, Mihajlovic, and the Allies. 28 Lorraine Lees, 11. 26 11 Combating the same Nazi occupiers as Mihajlovic, Tito’s Communist Partisans failed to win the same level of public support among wartime Americans. This, however, was not due simply to ideological considerations. Wartime Americans were just as concerned by the Partisan leader’s mysterious identity. Throughout the war, and well into the immediate postwar, rarely did one hear a consistent description of the Partisan leader. In many accounts, Tito suddenly “emerged from the Yugoslav fog” to lead the resistance against the Nazis. Others speculated that he was a Russian General playing the part after the original Tito had been liquidated in a Russian purge. Additionally, there was the possibility that he was a Ukrainian Jew, and even a U.S. citizen of Croat extraction who had once been a district organizer of the U.S. Communist Party. The name “Tito” was also said to have derived from the initials of Tajna Internacionalna Terroristicka Organizacija (Secret International Terrorist Organization), suggesting a wider communist conspiracy behind the Yugoslav’s rise to power29 These uncertainties were more than enough for Washington and mainstream Americans to overlook the efforts and legitimacy of Tito’s resistance movement. Still, it was not until after the war that Tito’s newly communist Yugoslavia came to be perceived as an actual enemy of the United States. Scholars have generally considered the immediate postwar as a period in which Yugoslavia distinguished itself as a “staunch ally” of the Soviet Union and by association an enemy of the United States. What is interesting, however, is that there was more behind Tito’s villainous postwar reputation in the United States than his ideological disposition and loyalty to Moscow. 29 Editorial, “Proletarian Proconsul,” Time, 16 September, 1946. 12 To be sure, U.S. observers were concerned that in postwar Yugoslavia “all roads (were leading) to Moscow”30 Tito had reneged on his wartime agreement to hold free elections and installed only communists in office. He committed to scrupulously following Stalin’s model of socialism and replicated Moscow’s economic planning organs, judicial system, state bureaucracy, health care, and cultural and educational spheres.31 On their own, however, these measures merely reflected the conduct of an ordinary Soviet satellite state, without agency or individuality. What elevated Tito above the standard satellite mold of enemy by association and made his regime a direct enemy of the United States was in many ways the same thing that led to his dispute with the Kremlin; that is, Tito refused to accept a subservient role for Yugoslavia and sought aggressively to demonstrate his freedom of action in what supposed to be a bipolar world. Americans witnessed firsthand this blatant disregard for order, authority, and all things American when in 1946 Tito ordered the downing of two unarmed American transport planes passing through Yugoslav airspace. Unprovoked, the incident and subsequent lack of cooperation by Yugoslav authorities alarmed American as well as Soviet observers.32 It was American citizens, however, who demanded swift justice, even if it meant military action.33 Tito’s public agreement to pay a $150,000 indemnity to the families of the killed airmen officially introduced the Yugoslav leader to mainstream America as a Soviet, and now, American problem. 30 As cited by Lorraine Lees, 17. Patterson to Pierre Cartier, 4 October 1946, Patterson Papers, File: Belgrade Correspondence C. This was how U.S. Ambassador Richard Patterson described the postwar situation in Belgrade to his friend and famous New York jeweler Pierre Cartier. 31 Perovic, 37. 32 Joseph and Stewart Alsop, “Kremlin is Even Leery of Tito,” Washington Post, 20 October, 1946. 33 Anthony Leviero, “Peace Threat Seen: Further Yugoslav Acts Will Not Be Tolerated, Washington Asserts,” New York Times, 22 August, 1946. Washington gave Belgrade 48 hours to release the survivors. The ultimatum was backed by a U.S. military march along the Morgan Line, which divided the contested Trieste area among British, American, and Yugoslav occupation forces. 13 Engaging and Embracing the Enemy 1948-1958 When the time came to decide on how to respond to Yugoslavia’s growing isolation and deteriorating humanitarian conditions at the hands of Soviet sanctions, U.S. officials cleverly allowed the Yugoslavs to raise the issue of extending aid, so as not to play the role of western opportunists. The nature of the initial Yugoslav aid request was two-fold: immediate food shipments due to a devastating drought, and weapons to stare down the increasingly aggressive Eastern Bloc nations with which they shared a border. From the outset, U.S. officials made little effort to conceal the fact that Washington, at the height of McCarthyism, would meet Yugoslavia’s needs. However, it was the tone of this aid commitment, a tone that the Eisenhower administration would adopt as well, which would mark the beginning of a new U.S. perspective on Yugoslavia. This tone was of a guarded and yet politically marketable long-term optimism. In rejecting Soviet domination, Tito’s Yugoslavia, although still communist, had taken an extraordinary first step and was on the road to “more freedom.”34 Bringing “more freedom” to Yugoslavia often amounted to Washington preaching patience, conceding that, for the time being, Tito was our son of a bitch. Yet the official government line also suggested that Yugoslavia was demonstrating the ability to evolve, adapt, and reason. These progressive capacities became points of emphasis which Washington insiders conveniently allowed to run free in main stream America. In some quarters, it would fall on deaf anti-communist ears. In other quarters, it would instill a –real or imagined – hope that U.S. aid could in the long-run make Tito’s regime more democratic - a Tito-Land. 34 35 Maurice J. Goldbloom, “Has Tito’s Regime Gone Democratic?” Commentary, 16 October 1954. The term “Tito-Land” was first used in a 1952 Time Magazine article. 35 14 Nowhere was this hope for a long-term Yugoslav transformation more noticeable than in the American print media. Prior to the extension of American aid, journalists and foreign correspondents rarely had anything interesting or positive to report on postwar Yugoslavia. One Saturday Evening Post writer, Ernest O. Hauser, referred to Tito as “Stalin’s model stooge” and a “Yugoslav Hitler” in a 1948 article.36 However, that same writer, in 1955 described Tito as a “civilized and distinguished world leader” with a “twinkle in his eyes that Americans could trust.” Much like the people he led, reported Hauser, “the evidence of Tito’s determination to move mountains figuratively and actually is almost everywhere.”37 This journalistic reversal was widespread and most apparent during Nikita Khrushchev’s much publicized visit to Belgrade in 1955. As the first Soviet official to step on Yugoslav soil since the Tito-Stalin split, foreign correspondents made sure to highlight the differences between the two leaders and the civilizing influence of U.S. aid. While Tito had become an international “success story,” Khrushchev and his Russian delegation were more often than not portrayed as “clumsy, pitiful, and bloodthirsty dwarfs.” 38 There was hardly a mainstream publication in America that shied away from these types of characterizations. The media in fact went beyond the government’s guarded emphasis on Yugoslav progressivism, misleadingly claiming that Tito had “defected” – when he was actually evicted – from the Soviet bloc.39 By 1955 many reporters were concluding that American aid had already created a functioning Tito-Land democracy, Ernest O. Hauser, “Stalin’s Model Stooge,” Saturday Evening Post, 1 February 1947. Ernest O. Hauser, “Tito: Cold War Middle Man,” Saturday Evening Post, 30 September 1955. For other journalistic transformations see, Fred Warner Neal, “Our Communist Ally,” Saturday Evening Post, 3 March 1951, and Demaree Bess, “Should We Do Business With Tito?” Saturday Evening Post, 10 September 1949. 36 37 38 39 The New York Times, Washington Post, Saturday Evening Post, U.S. News and World Report, and Time, at one time or another emphasized this point. 15 and that Yugoslavia was not merely, as Ambassador George V. Allen said “a work in progress.”40 Foreign correspondents, moreover, added a degree of legitimacy to TitoLand’s march toward democracy with an increasing number of optimistic and flattering eyewitness reports of progress from the streets of Belgrade.41 Among everyday Americans, though, there was little common ground. In government sponsored town hall meetings and letters to the editor, opinionated citizens debated the merits and drawbacks of unconditional aid to Yugoslavia. More often than not, however, Cold War Americans focused on the moral and religious implications of supporting a communist regime. The military advantages the aid program presented were not overlooked, but they did consistently place second on average taxpayer’s list of priorities; taxpayers, in other words, required much convincing before accepting and trusting wholeheartedly a communist ally. Interestingly, it was only after the decade of unconditional aid that the idea of a progressive and viable Tito-Land began taking root among the public at large. Historian John Lampe has described this development as the gradual creation of a “Yugonostalgia” – a sense that Yugoslavia had become a unique destination where the best Western ideas could co-exist and flourish alongside the best of what the East had to offer. This outlook first gained momentum during the era of American aid when the political establishment, mainstream media, and opinionated citizens weighed in on the future of Yugoslavia, and in effect, helped shape that country’s fascinating Cold War identity. 40 41 U.S. Department of State, Bulletin, Vol. 26, No. 380 (March 10, 1952), 381 Sherwin D. Smith, “Belgrade Through American Eyes,” Newsweek, 26 June 1950.