trematodes

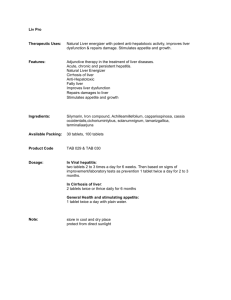

advertisement

1 TREMATODES Commonly known as the flukes, some trematodes are responsible for an acute and chronic inflammation of the liver and bile ducts, with resultant effects that are of considerable economic importance in cattle, sheep, goats, buffaloes, asses, deer, elk and moose. The principal and most widely distributed causal agent of severe liver infestation is undoubtedly Fasciola hepatica. Dicrocoelium dendriticum occurs but is of less pathological significance, while in North America and Europe the large American liver fluke, Fasciolides magna, is also found. Fasciola gigantica causes severe losses in cattle in Africa, and also occurs in Indonesia, Nepal, India and Japan. Fasciola hepatica* Fasciola hepatica (Distomum hepaticum) is the common liver fluke, and is distributed almost universally throughout the world. It is a pale brown in colour, flattened and oval in shape, anteriorly it terminates in an oral sucker that surrounds the mouth and a large ventral sucker situated about 2.5 mm behind the mouth. The parasite is 32 mm long and 8.4-13 mm wide. The eggs are brown, oval and provided with a lid or operculum. The cuticle of the adult parasite is studded with numerous backwardly directed spines that play an important part in the production of the typical liver (mechanical) lesions associated with the disease. Incidence of fascioliasis (distomatosis) F. hepatica is the most common cause of fascioliasis and occurs worldwide in three main forms (chronic, subacute and acute) as well as being involved in black disease. In England and Wales about one million sheep livers are condemned annually. Chronic fascioliasis is the most common disease of cattle encountered at meat inspection causing a 29% condemnation rate costing over 2 million pounds in liver losses and another 5 million pounds in lowered weight gain and carcase quality (e.g., In Northern Ireland the situation is relatively worse). 2 German authorities have estimated that the parasite may reduce beef production by up to 10%, milk production by 16% and the loss of flesh in affected sheep by 25%. Schemes to eradicate liver flukes in cattle on an area basis, involving routine treatment of all cattle and drainage of land combined with laboratory examination of faeces, have been successful in Germany. In Australia, cases of chronic fluke infestation are rare owing to the regular treatment of sheep in affected districts. There are, however, occasional heavy losses from acute fluke infestation. In the USA fascioliasis in sheep is not as prevalent as in Europe, owing largely to grazing sheep on higher and drier pastures. F. hepatica is most common in the sheep and ox but occurs occasionally in horses, pigs, rabbits and hares and sometimes in humans. The affection is occasionally found in the liver of adult pigs, particularly sows and pigs that have access to pasture, but sheep are the most susceptible and show the most severe symptoms and effects. Life history The adult liver fluke is hermaphrodite, and deposits ova in the bileducts of its host, usually the sheep or ox. A single liver fluke may lay over 1 million eggs in its life. When excreted the eggs will survive for some time, even through the European winter, though they are rapidly destroyed by desiccation. After passage of the eggs from the host by way of the bile and faeces, an embryo or miracidium develops whilst the egg is lying on the ground, and in 2-6 weeks in summer the embryo escapes from the egg shell via the operculum. The embryo is actively motile but dies within a few hours unless it encounters a suitable intermediate host, that, in the case of F. hepatica, is a mud snail, Limnea truncatula. In the USA Galba bulbimoides and Gb. techella are involved in the life cycle. The embryo enters the respiratory cavity of this snail, becoming transformed into an oblong sac known as a sporocyst, and in the next two to four weeks the sporocyst gives rise to six to eight rediae that are elongated structures each containing a sac-like intestine. In a further 4-6 weeks each redia becomes actively motile, migrates to the liver of the snail and eventually 3 rises to 15-20 cercariae that have an oral and ventral sucker, a long tail and bifurcated intestine. The cercariae escape from the rediae, leave the snail and find their way to a grass stalk or aquatic plant. The period of development in the snail is 6-10 weeks. The cercariae may either float on the surface of the water or they may attach themselves to a blade of grass, becoming encysted by the excretion of an adhesive substance, and resembling grains of sand. The period of development from egg to encysted cercariae takes 2 to 4 months, and cercariae may remain alive in a pasture up for to 12 months, and even in dry hay for a few weeks. A heavily water logged pasture enables carcariae to encyst further up the blades of grass where they are more likely to be ingested by herbivorous animals, and in this way a wet summer or autumn is always of serious import to sheep grazing on fluke-infested land. When grass or plants bearing cercariae are eaten by grazing animals, the cysts are dissolved in the small intestine of the host, and the liberated parasites pass from the intestine to the liver and develop into adult flukes. Infection The occurrence of liver fluke disease usually is inseparably connected with the life history of the snail L. truncatula that begins to be active in March or April and lays eggs that gives rise to a generation of snails, these producing more eggs 3-4 months later. As several generations of snails are produced between March and October there is thus a great increase in the snail population. The emergence of cercariae from the liver of the snail begins early in July, and the first outbreaks of acute of acute fascioliasis occur in sheep 6-8 weeks later. As F. hepatica requires about 3 months to develop from the cercarial stage into the adult fluke, and as cercariae are scarce on pastures until July, the chronic form of the disease does not manifest itself until late in the autumn, while marked symptoms do not appear until early winter and become more serious as the winter progresses. The continued infectivity of pasture is maintained partly by the ability of the fluke eggs and infective snails to whitstand adverse conditions, but mainly by the repeated reinfestation of land by carriers. 4 Symptoms Liver fluke infestation may assume an acute, subacute or chronic form. The acute form occurs within 3 weeks of infection, mostly in younger animals, and corresponds to the invasion of the liver by enormous numbers of young flukes. It has been shown experimentally that acute fascioliasis occurs in sheep if 5000 or more cercariae invade the liver and death due to massive hepatic haemorrhage may occur without clinical symptoms. The subacute form of the disease in sheep is due to infection with large numbers of metacercariae over a longer period of time resulting in loss of condition and anaemia. More frequently, symptoms of fluke infestation are observed in the chronic stage of the disease that occurs some months later and is manifested in sheep by a progressive anaemia and loss of condition and wool, oedematous swellings of the eyelids, throat and brisket and, at times, a pendulous condition of the abdomen. The animal then becomes weaker, diarrhoea ensues and the disease terminates in extreme emaciation and death. The systemic effects and the gross changes in the liver that are typical of this disease occur as a result of combined action of the: blood-sucking and, tissue-feeding capacity of the fluke, the irritant action of its suckers and cuticular spines, the continued absorption of metabolic products excreted by the flukes, an the effects of invading bacteria. Affected bovine animals, in contrast to fluke infestation in sheep, often show little impairment in bodily health, and markedly cirrhotic livers may be seen in the best nourished animals. Nevertheless loss of condition and of milk production may be marked. 5 In general, liver fluke affection in cattle is less acute than in sheep, and whereas 50 adult flukes are capable of producing clinical symptoms in sheep, some 250 are necessary to produce the same effects in cattle. On the African continent, however, the infection in sheep with F. gigantica is almost invariably of a peracute nature, for the ingestion of vast numbers of cercariae over a short period causes death from an acute haemorrhagic hepatitis. It has been shown that the incidence of Salmonella carriers, especially with S. dublin, is four times greater in fluke-infested cattle than in cattle that are not affected. Lesions The liver is the organ mainly affected by F. hepatica. Immature flukes bore through the intestinal wall in the abdominal cavity where they remain for a few days and then enter the liver trough its serous capsule. Large numbers of young flukes cause acute swelling and congestion of the liver, producing an acute parenchymatous hepatitis in which the serous capsule of the liver may be sprinkled with haemorrhages and covered with fibrin. Section of the organ at this stage shows numerous sharply circumscribed small lesions that, on pressure, exsude semi-fluid necrotic liver tissue and immature flukes. The liver is greyish in colour and in animals that have died suddenly may have ruptured with haemorrhage into the abdominal cavity. Clostridium oedematiens novyi can be proliferated in injured, necrotic tissue (black disease). Liver lesions associated with the acute form of the disease are seen towards the end of the summer and are succeeded eventually by lesions of a chronic type in which the fibrinous deposit on the serous capsule of the liver becomes organized and gives rise to a chronic perihepatitis. This is frequently manifested in both sheep and cattle by adhesion of the diaphragm to the anterior surface of the liver, or by adhesion of the liver and omentum. The presence of adult flukes in the bile ducts gives rise to mechanical irritation of these passages and results in a chronic, pericanalicular atrophying cirrhosis and the formation of connective tissue in the walls of the bile ducts and surrounding liver tissue. 6 In cattle the thickened and dilated bile ducts eventually become calcareous due to deposits of lime salts, and yellowish-brown bile containing adult flukes can be expressed when the ducts are incised. The liver fluke cannot reach the adult stage unless it settles in a bile duct, and those flukes that fail to reach a bile duct become encapsulated in the liver parenchyma, especially the left lobe, where they form large rounded prominences with brownish, greasy contents. In the USA the common liver fluke affecting cattle is Fasciolides magna, that migrates through the liver tissue but does not invade the bile ducts. Livers affected by this worm often show black melanin-like deposits, and sometimes a similar pigmentation is seen on the diaphragm or on the serous surface of the stomach where it is in contact with the liver. The black coloration is considered to be haematin, a breakdown blood pigment excreted by the parasite. In chronic fascioliasis of sheep the liver becomes irregularly lobulated and distorted, but the bile ducts, though thickened, dilated (because of accumulation of bile) and of a bluish colour, do not undergo calcareous infiltration. The fibrosis and calcification of the ducts, that is a feature of chronic fascioliasis in cattle, renders the habitat unfavourable to the adult parasite, and the life span of the adult fluke in the liver of cattle is as short as nine months, though it may extend to 2 years if the infestation is slight. The bovine apart from humans, is the only animal that develops calcification of the bile ducts as a result of Fasciola infection. The absence of calcification enables the adult fluke to survive for 5-12 years in the bile ducts of sheep. In the pig many immature flukes fail to reach the bile ducts and become encysted in the liver tissue where they form white, spherical nodules 38.4 mm in diameter, usually situated superficially and composed of an outer fibrous capsule with brownish or yellowish semi-solid contents. The relative rarity of adult flukes in the bile ducts of pigs is due to the prompt and efficient tissue reaction and the fibrous nature of the liver parenchyma that restricts the parasite to a zone immediately beneath the liver capsule. 7 Migratory flukes In cattle, immature flukes migrating through the liver parenchyma to a bile duct may penetrate a radicle of the hepatic vein and be transported to the lungs via the posterior vena cava and heart. The flukes are found near the base of the lung and produce round cyst-like areas the size of a hazelnut to a tennis ball that initially contain coagulated blood and immature parasites but later become calcified and exude a thick, dark brown slime when incised. Liver flukes are rarely found in sheep lung. Immature flukes may also be encountered in the mesenteric lymph nodes of both ox and sheep, being seen as millet seed to pea-sized nodules, calcified in some cases. More rarely, encapsulated immature flukes occur in the spleen, kidney, myocardium, subcutaneous tissue, beneath the parietal peritoneum and in the muscles of the diphragm. Control Control measures are directed at breaking the life cycle of F. hepatica by strategic treatment of the animal with a flukicide (albendazole, etc.) and snail control by the application of molluscides (e.g., copper sulphate, copper pentachlorphenate, and N-tritylmorpholene) and drainage of pasture. Copper compounds must be used with care because of their toxicity for stock, especially sheep, and possible pollution of streams. Biological control has been mooted following the discovery of developing forms of Echinostomatidae (trematodes similar to liver flukes) in samples of L. truncatula snails in which no developing forms of F. hepatica were detected, suggesting some form of antagonism between these two species. As yet, however, no actual antagonistic mechanisms have been proved. 8 Dicrocoelium dendriticum This parasite is lance-shaped. Two intermediate hosts are species of ants and land snails. The parasite is found in Northern Europe and in North-and South America. It is, in general, less pathogenic than F. hepatica, due probably to the absence of cuticular spines, and the liver fibrosis is finer than in F. hepatica infection. Human fascioliasis Humans are seldom infected by the common liver fluke. Infection in humans is acquired by the swallowing of encysted cercariae and not by the consumption of animal livers containing the adult parasite, and humans usually infect themself by eating watercress grown in water in which the snails are living and which is contaminated by the faeces of fluke-infested cattle or sheep. Fascioliosis in humans causes symptoms of urticaria and icterus with tenderness when pressure is exerted over the liver area. Recovery after treatment is the normal outcome. Judgement Markedly cirrhotic (tough with uneven surfaces) livers must be condemned as unfit for human consumption, though in bovine livers a minor affection confined to the bile ducts may be excised and the remainder passed (partial condemnation or excision). Affected livers are generally consigned for petfood or inedible byproducts and occasionally for pharmaceutical purposes (e.g., heparin and vitamin B12 production). The parasites in the liver die within a few hours of the host’s slaughter. The judgement of oedematous or emaciated sheep carcases depends on the extent of these pathological changes.