Consumer Informatics: The Elderly and the Internet

advertisement

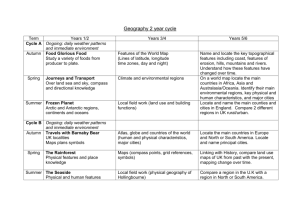

Consumer Informatics: The Elderly and the Internet Introduction The Internet has changed how people participate, evaluate and learn about factors relating to their own health care. [1] Over 93 million adults (Pew 03) now use the Internet to locate information about specific diseases, medical problems, medical treatments and procedures, diet and fitness, check out their physician’s credentials, and determine for themselves, the efficacy and safety involved in taking a specific medication.[2, 3 ] However, as Internet usage continues to grow, differences in how demographic groups use this resource to locate health related information are becoming more pronounced. In a survey by the University of Pittsburgh [4], it was discovered that 62% of the residents of Pittsburgh and surrounding Allegheny County had access to the Internet. However, the average older adult in Allegheny County, the second largest population of older adults in the nation [5], had the lowest levels of computer ownership and more limited access to the Internet than other county residents. Furthermore, these elderly adults, who make up 17.8% (228,416) of the county’s 1,281,666 residents lacked the essential knowledge of how to use the Internet to locate health information. Nationally, research[6] shows that older Americans are in danger of being cut off from one of the most provocative communication mediums of the 21st century. In the United States, older adults make up 13% of the population with only 4% using the Internet. Overall, 56% of America is online and out of that percentage, only 15% age 65 and over have direct access to the Internet[7] 93 million American adults use the Internet to locate health related information, with only 4 million aged 65 and older [8]. Furthermore, because older adults are more likely to use health care resources, knowledge of how the Internet can be used to locate health information to better one’s health care outcomes would benefit senior citizens. Thus, this study explored the impact the Internet had on older adults with regard to their beliefs in how much they participate in their own health care, and how they used the Internet to locate health information. Methods To facilitate the training of the elderly, a large suburban Pittsburgh public library and two senior community centers agreed to sponsor a series of Internet training seminars and made their resources available to the research team. The decision to use the library and the senior community centers as the settings for the training was based on the fact that elderly participants who did not have a computer at home could use the computers in these facilities to search the Internet. The choice of training centers also allowed the research team to reach a wide range of individuals with varying socio-economic backgrounds. The training sessions were advertised in two local newspapers, a local suburban magazine, and a local senior citizen newsletter. Flyers were also placed in the library and senior community centers where the training was to take place. The sessions were five weeks in length, meeting once a week for two hours. Participants were asked to commit to attending all five sessions. Each session began with an overview of the day’s topic, followed by intensive hands-on instruction and practice. The sessions used constructivist teaching techniques and self-directed learning. Constructivism emphasizes placing the learner in a situation where she learns to solve a specific problem—i.e. locate information related to her health care. This allows the learner to construct knowledge that is more meaningful and useful to the learner for recall in future problem solving scenarios. Each lesson used a different method for engaging the participant to find medical information that was relevant to her individual needs. Small groups of approximately 10-12 made individual attention possible for the hands-on portion of each session. A course packet was provided to the participants to serve as a reference for future use. Data Collection Pre and post questionnaires were distributed at the beginning and end of the five-week training session. The surveys were designed to capture baseline information about the participants experience using computers and their experience searching the Internet. The surveys also measured participants levels of anxiety toward computers, levels of self efficacy, and their health locus of control. The results of these measures are reported in Campbell (2004). To measure participants levels of perceived participation and heath information seeking behaviors, a 17 question Internet Survey was developed. This survey was designed to elicit participant’s feelings in three areas: level of participation in their health care, use of the Internet to locate health information, and use of the Internet to locate health information before and after a visit to their health care provider. Participants A total of 79 people, ages 60–83, with a mean age of 69.76, selfvolunteered for the Internet training, with 70 completing the five week program. Of those 70, 58 (83%) were female and 12 (17%) were male. Twenty-five (35.7%) had post-graduate training, 18 (25.7%) had a college degree, 12 (17.1%) had some college or technical degree, 12 (17.1%) had a high school degree, and 1 (1.4%) had less than a high school education. Fifty-four (77.1%) were retired, 4 (5.7%) worked full-time, 6 (8.6%) parttime, 1 (1.4%) was not employed, and 5 (7.1%) considered themselves home makers. Sixty-three (90%) had used a computer an average of 10 or more times, while only 7 (10%) had never used a computer. Fifty-three (76%) had a computer at home, while 17 (24%) did not. Those with a computer used it on average 4-6 times per week. Thirty-eight (54.3%) stated that they had used their home computer to search for information on the Internet, while 25 (35.7%) did not. Thirty-nine (56%) had made use of a computer in a public library or senior community center an average of 10 or more times, while 31 (44.3%) did not. Twenty-five used a public computer to search for information on the Internet, while 29 (54%) had not. Forty (57%) never used the Internet to search for health information, compared to 30 (42.9%) who had searched for health information on average for a total of 4-6 times. Forty-six (66%) had used electronic mail compared to 24 (34.3%) who did not. Sixty-five (93%) had never joined an online support group, chat room, or news group, while 5 (7.1%) had done so. Fifty-nine (84.3%) had a health problem, and out of that number, 45 (64.3%) had an illness that was chronic in nature. Eleven (15.7%) did not have a health problem. Finally, 56 (80%) of the participants believed that the Internet could be used to help them manage their health care, opposed to 14 (20%) who did not know. Results Descriptive statistics: Internet surveys were mailed to 70 participants. From that number, 52 (70%) completed surveys were returned. When asked if their levels of participation had changed since they were introduced to the Internet 33 (63.5%) said yes, while 19 (36.5%) said no. 45 (86.5%) had looked up health information on the Internet. Of those 45, 1 (1.9%) used the Internet daily, 5 (9.6%) used it weekly, 14 (26.9%) used it monthly and 24 (46%) responded to Other. 46 (88.5%) had seen a health care provider in the last six months. When asked what role they played in their last visit, 6 (11.5%) said that their doctor made all the decisions and they just followed them; 3 (5.8%) stated that they made the decisions and they asked their doctor to state his/her opinions; 39 (75%) stated that they played a collaborative role with their doctor, and that they worked together to make important decisions; and 2 (3.8%) selected Other. When asked if they had used the Internet prior to their visit with their doctor, 23 (44.2%) responded Yes, and 25 (48.1%) responded No. When asked if they used the Internet to prepare a list of questions for their doctor 18 (34.6%) said Yes, and 30 (57.7%) said No. When asked how many questions they asked their physician at their last visit, 3 (5.8%) asked one question, 23 (44.2%) asked two-three questions, 12 (23.1%) asked 4-5 questions, and 10 (19.2%) asked six or more questions. Asked if they had used the Internet to locate health information after visiting their health care provider, 19 (36.5%) said Yes, while 27 (51.9%) said No. Finally, when asked if they had a set of medical web sites they used to retrieve health care related information, 25 (48.1%) said Yes, and 18 (34.6%) said No. Inferential Statistics: To gauge perceived levels of participation in their health care, participants were asked two questions. The first question asked participants to rate, on a scale of one to five, with one being no participation and five high participation, what their levels of participation were before they were introduced to the Internet. A second question, asked participants to rate their current levels of participation on the same scale. Using a Wilcoxian Signed Ranks Test, significance (.000) was found between the two scores. Meaning, after participants were introduced to the Internet, they perceived that their levels of participation in their health care increased. Textual Comments To gain more insight into how participants used the Internet to locate health information, and how that information influenced their relationship with their health care provider, participants were asked the following five questions: 1. What type of Health Information did your search for? 2. What influence, if any, did the Internet have on your relationship with your health care provider. 3. Did you share the information with your health care provider. 4. If you used the Internet to locate health related information after a visit with your health care provider, for what purpose did you search the Internet? 5. What anecdotes do you want to share regarding your experiences using the Internet to locate health information? The responses to question one were broken down into three categories: General Topics (26 (57%)), information such as throat swallowing, back surgery, cochlear implants, and blood pressure; Medication Information (16 (35%)), and Specific Information (3 ( 6.6%)) such as “How do you treat liver disease”, or “What causes cloudiness in the cornea after cataract operations.” Responses to the question: What influence, if any, did the Internet have on your relationship with your health care provider, were grouped into four categories: No Change, Improved Communication, Personal Empowerment, and Conflict. 12 (26%) participants reported No Change in the relationship they had with their health care provider, while 11 (24%) reported that Internet use Improved Communication with their provider. Typical comments in this category included: “I gathered information about my condition and discussed it with my physician.”, and “My interest and participation in my health care was accepted. In fact, it influenced changing of medications and seeing another M.D.” In the third category, Personal Empowerment, 19 (42%) gave responses that illustrated a more confident, self actualized individual who was not intimidated by their health care provider. The Internet, based on participant’s comments, gave them the power they needed to play a more active role in their health care. Responses from this category included: “I feel that I am more comfortable asking questions when a medication is prescribed. I’m not as intimidated since I feel that I possess the tools to check when in doubt”, and “I am not as hesitant in asking questions about my own health and making suggestions for possible treatment.” The final category, Conflict, found several participants 3 (6.6%) had an adversarial relationship with their provider. Use of the Internet to locate health care information placed a strain on the relationship and created friction between the participant and their health care provider. Comments in this category included: “The Specialist/Oncologist didn’t have the facts and information that I had. When I asked questions he was very vague. I was not willing to take the medication (and told him so) and he wrote out the Rx anyway and then tried to end the appointment as soon as he could. He didn’t seem to like my questions and my ability to think about my decisions”, and “I moved from one doctor to another. The first one was bored. The second one was not too receptive of my mentioning the Internet..” The third question: Did you share health information found on the Internet with your health care provider? If so, what was their response, revealed that participant replies fell into one of three groupings. Participants either Did Not Share Information, Did Share Information and Received a Positive Response, or Did Share Information and Received a Negative Response. In the first grouping, 18 (40%) participants did not share health information with their provider. In the second grouping, 16 (35%) participants shared information and received a positive response. Comments included: “[Physician] Pleased and encouraged me to learn and be involved with my care in whatever method that opened up to me”, as well as, “He [physician] was very interested.” In the third grouping, 11 (24%) participants shared information with their provider but received a negative reaction. In this grouping participant’s comments showed initial defensiveness on the part of their health care provider to total disregard to the information found on the Internet. Cogent comments include: “Most doctors have been defensive. My mother’s primary care doctor, although a bit defensive, realized that I knew all about her disease and that I knew more about the newer treatments that he did. He was willing to compromise with me on the treatments”, and “Don’t believe all you see and hear; lots of ‘experts” around’, as well as, “He [physician] wasn’t familiar with it and said something disparagingly: ‘I don’t know where you got your information.’” Question Four asked participants whether they used the Internet to locate health information after a visit with their health care provider. 19 participants identified themselves as having done so, and from their comments, three distinct categories appeared. After a visit to their doctor, participants either used the Internet to Check on Medications, find Updates to Information Concerning a Specific Health Problem, or to Verify Information they were told during their most recent visit to their health care provider. In the Category One, 8 (42%) participants used the Internet to learn more about prescribed medications and their contraindications. Typical comments in this category included: “To determine the side effects of medication prescribed”, and “Checking on interaction of medication.” In Category Two, 3 (15%) participants, used the Internet to find updates on information related to their own health problems. A typical comment in this category was: “I again compared the different sites to see if any updates had occurred, as you know health information always been updated by new research.” The final category, found 8 (42%) participants used the Internet to verify what their health provider had told them during their last visit. A typical comment found in this category was: “To verify validity of health provider’s information.” The final question asked participants to share Anecdotes that typified unique experiences they encountered using the Internet to locate health information. From those comments, five categories appeared. Those categories included: No Unique Experiences, General Comments, Constraints, Enjoyed Introduction to the Internet, and Positive Health Outcomes. The first category, contained 16 (35%) participants who did not have any unique experiences to share. In the second category, 3 (6.6%) participants made general comments in reference to their Internet experiences. A typical comment was: “Sometime I have to read a lot of material to find satisfying information. Many times I learn information that my doctor is not aware of. Sometimes the side effects of medicines are frightening.” 6 (13%) participants in the Category Three experienced constraints when trying to use the Internet to locate health information. For instance, one participant stated: “Since I use WebTV, it is sometimes difficult to access some websites, especially JAVA is not accessible with WebTV.” Another participant voiced another type of constraint that is endemic to older populations: “ Illness has prevented my access to the Internet. I am improving now….and plan to use the Internet for medical and health information.” In Category Four, 10 (22%) participants made statements that showed how much they enjoyed being introduced to the Internet. A typical comment was: “Excellent course and materials. I plan to use them for reference when needed.” In the final category, participants 8 (17%) provided remarks that detailed how their use of the Internet lead to positive health outcomes. The following comment is typical of those found in this category: “I think the use of the Internet helped save my mother’s life. She had clostredeum difficile and a bacterial infection that was not responding to antibiotics. I was able to discuss the mechanics of the disease with my mother’s doctor. He was willing to try a different drug along with probiotics. I knew that the pro-biotics he suggested and the dosage was too low and ineffective. I then told him that I used a more powerful pro-biotic in a much stronger dosage. But it worked!” Conclusion The results of this study revealed two significant conclusions. First, even though the population of this study was based on a group of self volunteers, it is evident that women have an active interest in using the Internet to locate health information. The fact that more women than men volunteered to take part in the study is not surprising as past research [10,11,12,13] shows that women actively participate in their own health care and ask more questions during office visits. Use of the Internet to locate health related information would be one more tool in a woman’s arsenal to further enable her participatory roles.[9] The second conclusion is that the Internet provided older adults with both perceived and actual abilities to participate in their own health care. When asked if they participated more in their health care since being introduced to the Internet, 33 (63.5%) participants answered yes. This fact was further substantiated by a Wilcoxian Sign Test that showed subjects experienced significant (.000) levels of perceived participation in their health care once they began to using the Internet to search for health care information. When questioned further, participants felt that the Internet empowered them to ask more questions of their health care provider, and to use the Internet as a means of verifying information shared with them by their provider. Discussion Recent research[7] shows that as older adults go online, a majority (53%) of them will use the Internet to locate health related information. Subjects in this study were most interested in locating information on general health topics, prescription drugs, and to verify what they had been told by their health care provider. As older adults begin to use the Internet, this study shows that they begin to perceive themselves to be taking a more participatory role in their health care, and to work more collaboratively with their health care provider. . Future studies should look at more quantitative methods of validating older adults claim of greater participation in their health care. For example, during a visit with their health care provider, do older adults using the Internet, ask more questions of their provider, and ask for more detailed explanations in regards to a specific health problem. Another important consideration is how to get more men involved in using the Internet to find health care information. In this study and others [8 ] a majority of the participants were women.. Studies have shown that patients who ask questions, elicit treatment options, express opinions, and state their preferences regarding treatment during office visits with their physicians have measurably better health outcomes than those who do not communicate.[14] Therefore, engaging these individuals could impact their health outcomes. Another area ripe for future research is how Internet usage by the elderly impacts costs, utilization, and overall health. For example, does use of the Internet lead to quicker diagnosis, treatment, and recovery, therefore, eliminating present and future burdens on an already stressed health care system. Or does Internet usage lead to higher utilization of services because patients request that more tests and procedures be performed to diagnose a particular health problem, even when those tests are not warranted. Finally, does Internet use to locate health information truly help the elderly who are ill get better quicker, and those who are healthy maintain their present state? References: 1. Fox, S., Rainie, L., The online health care revolution: How the Web helps Americans take better care of themselves. 2000, The Pew Internet & American Life Project: Washington, D.C. 2. Ferguson, T., Online patient-helpers and physicians working together: a new partnership for high quality health care. British Medical Journal, 2000. 321(7269): p. 1129-32. 3. Campbell, R. J., Consumer Health, Patient Education, and the Internet Internet Journal of Health, 2001. 2(2). Available online at: http://www.ispub.com/ostia/ index.php?xmlFilePath=journals/ijh/ vol2n2/consumer.xml 4. The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs., Consumer health information in Allegheny County. An environmental scan. 2000, University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA. 5. Rostein, G., Allegheny still second oldest big county in United States, in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 2001: Pittsburgh, PA. 6. Brodie, M., Flournoy, RE, Altman, DE, Blendon, RJ, Benson, JM, Rosenbaum, MD., Health information, the Internet, and the digital divide. Health Affairs, 2000. 19(6): p. 255-65. 7. Fox, S., Wired Seniors: A fervent few, inspired by family ties. 2001, The Pew Internet and Life Project: Washington, D.C. 8. Fox, S., Rainie, L., Vital decisions: how Internet users decide what information to try when they or their loved ones are sick. 2002, The Pew Internet & American Life Project: Washington, D.C. 9. Campbell, R. J., Older Women and the Internet. Journal of Women & Aging, 2004. 16(1). 10. Arora N.K., McHorney, C.A. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Medical Care, 2000. 38(3):335-341. 11. Wallen, J., Waitzkin, H & Stoeckle, J.D.. Physician stereotypes about female health and illness. Women Health, 1979. 4, 135-146. 12. Mechanic, D. Sex, illness behavior and use of health sciences. Social Science & Medicine, 1978. 12B: 207-214. 13. Nathanson, C.A. Sex, illness and medical care. Social Science & Medicine, 1977. 11: 13-25. 14. Kaplan, S., Greenfield, S., Ware, JE Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care, 1989. 3 Suppl: p. S110-27.