The Daughters of Tzlofhad

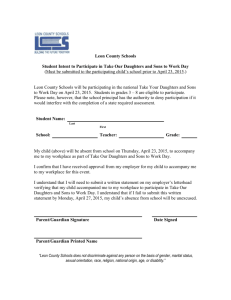

advertisement

Bar-Ilan University Parshat Hashavua Study Center Parshat Pinchas 5774/July 12, 2014 This series of faculty lectures on the weekly Parsha is made possible by the Department of Basic Jewish Studies, the Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, the Office of the Campus Rabbi, Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity and the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. For inquiries, please contact Avi Woolf at: opdycke1861@yahoo.com. 1076 The Daughters of Tzlofhad: Devoted to the Land and Noble By Nathan Keller* The daughters of Tzlofhad appear in two weekly readings of the book of Numbers. In this week's reading (Num. 27:1-5), they approach the leaders of the people to petition for the inheritance of their deceased father, who left no male heirs, to be given to them so that they could perpetuate their father's name. The end of the book (Num. 36:10-12) records that they were wed to their uncles' sons so that their father's inheritance would not pass to another tribe upon their marrying. The daughters of Tzlofhad are considered paragons of wisdom and virtue. "The daughters of Tzlofhad were wise women, they were exegetes, they were virtuous" (Bava Batra 119b). Upon first glance at the text it is not clear why the behavior of the daughters of Tzlofhad was considered so very noble. Here we shall discuss two points concerning the story of Tzlofhad's daughters, using hints in the text and homilies of the Sages, which may be viewed as completing the picture sketched by the text, in an attempt to understand what was so exceptional in the behavior of these women. * Dr. Nathan Keller teaches in the Department of Mathematics. 1 The timing of the request by the daughters of Tzlofhad Rashi, elucidating the juxtaposition of the story of the daughters of Tzlofhad to the story preceding it, writes (Num. 26:64): The decree consequent upon the incident of the spies had not been enacted upon the women, because they held the Promised Land dear. The men were saying, "Let us head back for Egypt," why the women were saying, "Give us a holding." Therefore the account of the daughters of Tzlofhad was juxtaposed to this story. According to Rashi, the request of Tzlofhad's daughters, "Give us a holding," stemmed from their appreciation of the Promised Land and was representative of the attitude of the women, who held the land dear, as opposed to the men, who wished to return to Egypt. Rashi's commentary requires clarification: how does the request by the daughters of Tzlofhad attest to their love of the land? After all, they were asking for something that would be of benefit to them! Also, the comparison with the men, who said, "Let us head back to Egypt," is unclear: this verse appears in the context of the sin of the spies, which took place 38 years earlier! The answer, in our view, lies in understanding the timing of the petition to Moses by Tzlofhad's daughters. At the beginning of the passage on the daughters of Tzlofhad it says: "They stood before Moses, Elazar the priest, the chieftains,…" (Num. 27:2). From the reference to Elazar the priest, Rashi deduces: "This tells us that they stood before them in none other than the fortieth year, after Aaron had died." What was the spirit of the nation at that time? According to the Jerusalem Talmud (Sotah 1.10), the situation was far from simple. Rashi cites the Jerusalem Talmud (with slight variation; on Deut. 10:6): When Aaron died at Mount Hor at the end of the forty years and the Clouds of Glory disappeared, you grew fearful of attack by the king of Arad, and appointed a leader that you might return to Egypt, and so you turned back eight stages, as far as Bene-Yaakan and from there to Moserah. There the Levites fought you and slew some of you, and you some of them, until they forced you back on the road along which you had retreated. According to the midrash, not only were the people not preparing to enter the land, rather on the contrary, they were making another attempt to return to Egypt, an attempt stopped by the Levites by force of arms. We can say it was at this moment that the daughters of 2 Tzlofhad came forward with their petition for a holding in the land. This explanation fits in well with another midrash: This is to inform you at what time they stood before Moses. At the time that the Israelites were saying to Moses, "Let us head back to Egypt." Moses said to them: How can it be that all the Israelites are asking to return to Egypt, and you are asking for a holding in the land? They said: We know that ultimately all Israel will have a holding in the land (Sifre Zuta 27a). Had the reference to the Israelites' words, "Let us head back to Egypt," referred to the verse in the passage on the spies (Num. 14:4, as indicated in the references given in the midrash), we would have no option but to say that this midrash is allegorical, because of the gap in years between these events. But, by what we have said, we can claim that it was describing the actual situation. At that moment, as the people were beginning to turn back towards Egypt, the daughters of Tzlofhad approached Moses and petitioned for a holding in the land. Moses was surprised at their action: You wish to receive a holding now, at a time when everyone seeks to retreat?! Yes, they responded confidently. "We know that ultimately all Israel will have a holding in the land." According to this explanation, the daughters of Tzlofhad not only had the courage to stand before the entire community and petition for inheritance. Rather, they had the courage to come out against the spirit of discouragement prevailing in the public and express their unreserved faith in inheriting the land. Thus the daughters of Tzlofhad indeed brought to its peek the women's characteristic of holding the promised land dear and constantly aspiring to reach it—which was not so of the men, who, displaying a total lack of courage, sought to return to Egypt, as explained in Rashi's remarks with which we began. The marriages of the daughters of Tzlofhad The gemara (Bava Batra 119b) writes that the daughters of Tzlofhad were virtuous "since they were married to such men only as were proper for them." What made this act so praiseworthy as to constitute proof for the Sages of the virtue of the daughters of Tzlofhad? To understand the gemara, we must examine the second passage in which the daughters of Tzlofhad appear. The tribe of Manasseh turned to Moses and complained that when the daughters of Tzlofhad marry, their father's inheritance that they received would likely be transferred to another tribe. Their grievance won divine approbation: The plea of the Josephite tribe is just. This is what the Lord has commanded concerning the daughters of Tzlofhad: They may marry anyone they wish, 3 provided they marry into a clan of their father's tribe…Every daughter among the Israelite tribes who inherits a share must marry someone from a clan of her father's tribe, in order that every Israelite may keep his ancestral share. (Num. 36:5-8) It was stipulated that any other woman in a similar situation to the daughters of Tzlofhad must marry a man from her own tribe in order to prevent transferring inheritance from one tribe to another. But what was determined regarding the daughters of Tzlofhad themselves? The gemara writes (Bava Batra 120a): The daughters of Tzlofhad were given permission to marry someone from any of the tribes, for it is said: They may marry anyone they wish. How, then, may one explain [the text], "provided they marry into a clan of their father's tribe"? Scripture gave them good advice, [namely], that they should be married only to such as are proper for them. According to the gemara, the Torah gave the daughters of Tzlofhad freedom of choice, but noted that in order to maintain the division of the land into ancestral portions, it would behoove them to wed men from their own tribe, as all other women in their situation were required to do. The daughters of Tzlofhad were praised for "marrying only such as are proper for them" because they consented to limit their freedom of choice in marriage in order to fill the Lord's will that inheritance not be transferred from tribe to tribe. Substantiation for this reading of the text can be found in the verses describing the marriages of the daughters of Tzlofhad: The daughters of Tzlofhad did as the Lord had commanded Moses…Tzlofhad's daughters were married to sons of their uncles,…so their share remained in the tribe of their father's clan. (Num. 36:10-12) Before we are told whom Tzlofhad's daughters married, we are told that they did as the Lord had commanded. According to our analysis, this verse serves to emphasize that their reason for choosing spouses as they did was their desire to fulfill the Lord's will. Sforno (loc. cit.) interprets the text similarly: "Their intention was to do the will of their Maker, as the Lord had commanded Moses, not because they wanted the men they married." Great virtue was shown in giving up the explicit leave given them by the Torah to marry whomever they chose in favor of upholding the Lord's will. We shall see, however, that the virtue of Tzlofhad's daughters went far further. The midrash (Numbers Rabbah 21.11) embellishes on the gemara's explanation of their virtue: 4 They were virtuous for marrying only such as were proper for them. But why did the Holy One, blessed be He, introduce them to Moses at the end of his career? In order that Moses might not plume himself on having separated from his wife for forty years. The Holy One, blessed be He, informed him through these, saying: "Here are women who have not been commanded and yet only married such as were proper for them." According to the midrash, the Holy One, blessed be He, presented the daughters of Tzlofhad to Moses as an example so that he not boast of having separated from his wife Zippora in the wake of the Lord's commands and having lived without a wife for almost forty years. Apparently the daughters of Tzlofhad were used as an example because they, too, waited forty years in order to marry men proper for them, even though they had not been so commanded. Why did they have to wait so many years? We could say that the reason for their waiting was their desire to perpetuate their father's name in the best way possible. Ever since their father Zelophehad had died without male heirs, early in the period of the Israelites' wandering through the wilderness, his daughters had been wondering what would become of his inheritance. In their estimation it would be fitting for them to receive the inheritance and thus perpetuate their father's name, and so they hoped would happen. But they also considered the difficulty that would arise if they were to marry outside their own tribe: their father's inheritance would pass to their husbands and would become the property of another tribe. They did not know whether or not they should refrain from so doing, and therefore they waited to see what the Lord would command. The ruling in this regard was not given until the fortieth year. Tzlofhad's daughters were given permission to marry whomever they chose, but all other women in their situation were commanded to marry within their tribe. The daughters of Tzlofhad concluded from this that the Lord's will was for inheritance not to shift to other tribes and therefore finally gave up their freedom of choice in marriage and were wed to sons of their uncles. Such tremendous sacrifice of one's private life for the sake of the ideal of perpetuating their father's name and not causing detriment to the ancestral inheritance of the land of Israel is almost inconceivable. And they did all this even though they had never been commanded and had even been given permission explicitly not to do so. This made the deed of Zelophehad's daughters so very noble that it could be brought as an example to Moses. Translated by Rachel Rowen 5