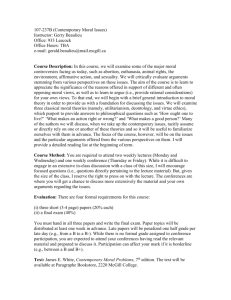

The moral status of beings who are not persons

advertisement