Tenth Session-Criteria for evaluating

advertisement

Tenth Session: Criteria for evaluating environmental policies, emission taxes, costeffectiveness, and subsidies; Transferable discharge permits (TDPs); environmental

policies in perspectives; Environmental policies in Canada, Policy response-The Kyoto

Protocol, carbon taxes, designing issues; Green taxation

Chapter-9: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

Environmental policy analysis: Public-policy problems arise when there is a discrepancy

between the actual level of environmental quality and the preferred level. The available public

policy are decentralised policies; liability laws, property rights, market responses-green goods,

moral suasion; command- and control policies; standards; incentives-based policies: taxes and

subsidies, transferable discharge permits.

Criteria for evaluating Environmental policies:

There are many different types of environmental policies. Criteria for specific environmental

policies are the following:

Ability to achieve efficient and cost-effective reductions in pollution

Fairness

Incentives offered to people to search for better solutions

Enforceability

The extent to which policies agree with certain moral precepts.

Efficiency and cost-effectiveness

By efficiency means the balance between abatement costs and damages. An efficient policy is

one that gives the point (either emissions or of ambient quality) where marginal abatement costs

and marginal damages are equal. Environmental policies are a continuum from centralized to

decentralize. A centralized policy requires some administrative agency for determining what is to

be done. Here the regulatory agency in charge would have to know the relevant marginal

abatement cost and marginal damage functions, then take steps to move the situation to a point

where they are equal.

A decentralized policy gets results from the interaction of many individual decision makers, each

of whom is essential making his or her own assessment of the situation. Here marginal abatement

costs and marginal damages and adjust the situation toward the point are equal. In either

situation, society is much better off with a cost–effective policy. Cost effectiveness is a key

policy criterion when regulators cannot measure the MD curve; minimize the total costs of

reaching a given target level of environmental quality; and allow society to achieve higher target

level of environmental quality than inefficient policies because of cost savings. Cost

effectiveness becomes an important issue in industrialized countries during times of recession or

economic stagnation.

Fairness: Fairness or equity is another important criterion for evaluating environmental policy.

Equity is a matter of morality and relatively well-off people have more benefit than those less

fortunate.

Incentives for innovation: It is important criterion that must be used to evaluate any

environmental policy is whether that policy provides a strong incentive for individuals and

groups to find new, innovative ways of reducing their impacts on the ambient environment. So

provide education and training that allow people to work and solve problems more efficiently.

The greater incentives the better the policy, at least by this criterion.

Enforceability: Imposing regulations and ensuring that they are met requires the resources of

people, time, and institutions. Policies have t be enforced through the monitoring of emissions or

technologies used, negotiations with polluters about timetables for compliance, and legal system

used to address violations of a law. There two main steps in enforcement: monitoring and

sanctioning. Monitoring refers to measuring the performance of polluters in comparison to whatever requirements are set out in the relevant law. Sanctioning refers to the task of bringing to

justice those whom monitoring has shown to be in violation of the law. The objective of

enforcement is to get people to comply with an applicable law. Thus some amount of monitoring

is normally essential; the only policy for which this does not hold is that of moral suasion.

Enforcement of sanctioning is important for those who violate the law.

In Canada, negotiation between polluters and government agencies is a common method of

obtaining compliance. Another practice is for agencies to require self-reporting of emissions by

firms. Public authorities carrying out periodic audits of records and do periodic testing of

emissions. The costs of enforcement, though perhaps not as large as overall compliance costs in

most cases, are critical to the success of environmental quality programs and ought to be treated

explicitly in evaluating the overall social costs of these programs.

Moral considerations: Polluters might very well respond more quickly and with greater

willingness to a subsidy program than to one that is quickly and with greater willingness to a

subsidy program than to one that is likely to cost them a lot of money. Subsidies might be the

most effective. There is much moral appeal in the notion that the “polluters should pay.”

Polluting behavior is immoral. Hence the state should adopt [policies that make certain types of

polluting behavior illegal.

Chap-12: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

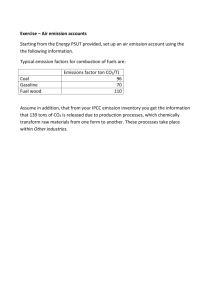

Emission taxes and subsidies: There are basically two types of market-based incentive policies:

(1). Taxes and subsidies and

(2). Transferable discharge permits.

Both require a regular to put the program into effect and to monitor outcomes, so they are less

decentralized than liability laws or letting parties barging over emission levels. Regulators set a

price for pollution via taxes and subsidies and set quantities of allowed emissions with

transferable discharge permits. The market determines the price of [pollution under the permit

approach. Economics have long promoted the idea of incorporating incentive-based policies

more thoroughly into environmental policies.

Emission Taxes: The essence of the tax approach is to provide an incentive for the polluters

themselves to find the best way to reduce emissions, rather than having a central authority

determine how it should be done. Total private cost of compliance of an emission tax is defined

as the sum of abatement costs and the tax bill for the polluter. Polluters will minimize their total

private costs by reducing emissions until the tax rate equals their marginal abatement (

mitigate/reduce) cost.

The Socially Efficient Tax: Social costs of compliance include only the real resources used to

meet the environmental target; they do not include the tax bill. Taxes are transfer payments,

payments made by the polluters to the public sector and eventually to those in society who are

benefitted by the resulting public expenditures. The polluter itself may be a recipient of some of

these benefits. Transfer payments are therefore not a social cost of the policy. The total social

costs of compliance are the polluter’s total abatement costs. Society is interested in the net social

benefits from the tax policy. Net social benefits of a policy are defined as the total damages

forgone net of the social costs of compliance.

Emission Taxes and Cost-effectiveness: The imposition of an emission tax will automatically

satisfy the equimarginal principle because all polluters will set the tax equal to their MAC curve.

MACs will be equalized across all sources.

Emission Taxes vs Standards: When MACs differ among polluters, social compliance costs are

lower under a tax than a uniform standard meeting the same target level of emissions because the

tax is cost-effective and the uniform standard is not. Another difference between taxes and

standards is that an emission tax is cost-effective even if the regulator knows nothing about the

marginal abatement costs of any of the sources. Standards have the appearance of placing direct

control on the thing that is at issue, namely emissions. Emission taxes place no direct restrictions

on rates in response to the tax. This may make some policy-makers uneasy because firms still

allowed to control their own emission rates. The main advantage of emission taxes is their

efficiency aspects: The polluters will adjust their emission rates so that the equimarginal rule is

satisfied. The administrators do not have to know the individual source of marginal abatement

cost functions for this happen. Firms faced with the tax and then left free to make their own

adjustments. (2) the second advantage of emission taxes is that they produce a strong incentive to

innovate, to discover cheaper ways of reducing emissions. An advantage of emission taxes is

that they provide a source of revenue for public authorities. Emission taxes require effective

monitoring. They cannot be enforced simply by checking to see if sources have installed certain

types of pollution-control equipment. Emission subsidies would have the same incentive effect

on individual polluters, but they could lead to increase in total emission levels.

Zoned Emission Tax is an emission tax that is set at different level across regions or zones

within a jurisdiction. This is done to reflect non-uniform emission of a pollutant. Zoning is a

command-and control policy that specifies types of land uses allowed within the jurisdiction.

Zoning regulations can prohibit private activities that are deemed detrimental to the public if they

occur in certain areas. For example, industrial uses of land are typically prohibited in residential

neighborhoods.

Waste reduction: Methods of reducing the amount of material that needs to be disposal of in

society. Reduction can be accomplished by recycling residuals back into the production process

and by shifting technologies and operations so that the amount of residuals discharged is

reduced.

Chapter-13: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

Transferable discharge permits (TDPs)

Transferable discharge permits is a decentralized market interactions of polluters themselves. It

creates a transferable property right to emit a specified amount of pollution. Key points of a TDP

policy:

1. Like a standard, permits ensure that a target level of pollution is achieved

2. Like a tax, transferable permits that are traded in a competitive Market are a costeffective

3. Regulators do not know each polluter`s MAC curve to find the right `price` that achieves

cost-effectiveness. The market does this automatically, because polluters set the permit

price equal to their MAC.

4. Once the target level of pollution is set, the market will reveal a polluter`s MAC curve

5. Trading occurs if the MACs of polluters are sufficiently different so that some will

become sellers of permits and the others, buyers

6. The exchange of permits provides each trader with cost savings compared to their initial

permit allocation from the regulator.

Issues in setting up a TDP market:

(1) The initial rights allocation;

(2). Establishing trading rules;

(3). Non-uniformly mixed emissions.

A world carbon trading system is being investigated by a number of countries and companies are

actually engaging in trading carbon in anticipation of this market. TDP programs are being

contemplated in Canada for carbon trading, nitrogen oxide, and volatile organic compounds.

TDP programs come with their own set of problems. Both transferable discharge systems and

emission tax systems seek to take the burden and responsibility of making technical pollutioncontrol decisions out of the hands of central administrators and put them into hands of polluters

themselves. It is important to stress the following points: Incentive based policies such as TDPs

and taxes are not aimed at putting pollution-control objectives themselves in to the hands of the

polluters. It is not the market that determines the most efficient level of pollution control for

society. Rather, the policy instruments are means of enlisting the incentives of the polluters

themselves in finding more effective ways of meeting the overall objective of reducing

emissions.

Chapter-14: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

Environmental policies in perspective

Two ways to measure costs of policy compliance:

(1) Private compliance costs-measure the total costs of abatement incurred by the polluter. This

is the polluters total abatement costs (TAC) plus any taxes paid or transferable discharge

permits (TDPs0 purchased (a cost or sold (a revenue).

(2). The social compliance costs are defined as the private compliance costs borne by the polluter

net of any redistribution back to polluters of tax or discharge permit revenues collected by

the government. These revenues will not influence any decisions on the margin, if they are

given back to polluters in lump sums.

These two policies differences help explain polluters` support for or opposition to the

implementation of policies. The incentives created by each policy to invest in pollution

abatement equipment, and the information required by regulators to implement the policy help

regulators choose a policy for each particular pollution problem. No single policy is appropriate

for all types of pollution. Incentive- based policies reveal information about the MA curve of the

polluter, while standards do not. Under a TDP, social efficiency can be reached by adjusting the

number of permits. Standards create an incentive for polluters to reveal a MAC curve. Taxes and

TDPs do not create this incentive. Taxes may, induce polluters to reveal to regulators a MAC

that is lower than their true curve. This is unlikely that this will occur with TDPs.

Chap-15: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

Environmental policy in Canada-an overview: Economic efficiency one possible way is

through environmental equity policy. Other motivation includes equity (ensuring a fair

distribution of benefits and costs of meeting environmental targets across income group),

regional diversity, and political factors (ideological beliefs). Governments are also constrained

by constitutional powers, legislative constraints and the presence or absence of particular

institutions. Two features those are fundamental to the Canadian regulatory system for the

environment: (1). The constitutional division of power between the federal and provincial

governments and (2). Environmental regulation works in Canada’s parliamentary system.

Constitutional powers over the environment: Section 91 of the Constitution ACT (1967)

establishes federal power over ocean and inland fisheries (section 91{12}, navigation and

shipping (section 91{10}, and federal lands and waters.

These powers have been used by the federal government to enact legislation that has some

element of pollution control. Fisheries power the Fisheries Act, Navigable Watters Protection

Act and the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act. Canadian Environmental Protection Act

also includes toxic materials legislation. Federal has the power to negotiate international treaties;

and to implement national concerns under the principle of Peace, Order, and Good Government.

Provincial Powers: The key to understanding Canadian environmental policy is to recognize

that most regulatory powers applicable to the environment lie with the provincial governments.

Most of the provincial powers come from section 92 of the constitution. Under section 92, the

provinces have power over local works (section 92{10}, property and civil rights within the

provinces (section 92[13], matters of a local or private nature (section 92 [16], and authority over

provincially owned lands and resources (section 92[5]; 109. A 1982 amendment to the

Constitution Act 9section 92A) strengthened the provincial powers over its natural resources.

This gives power to provincial government t jurisdiction over the development, conservation,

and management of its non-renewable resources-energy resources, forests and hydroelectric

power facilities. There are some constitutional power policies. There are conflicts still exist in

Canada. (1) lack of clarity and overlap of jurisdictional responsibilities, and (2) conflicting

objectives between the federal and provincial governments. Concurrent legislation can lead to

overlap in regulation and potential for confusion and high costs of compliance to polluters. The

regulatory process in Canada is highly dependent on the interests of the party in power under the

parliamentary system.

Chap-20: Field, Barry and Olewiler, Nancy (2002). Environmental Economics. Toronto:

McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited.

Human and Ecosystem Impacts: Global warming is expected to bring a general rise in sea

level because of the expansion of sea water, the melting of glaciers, and perhaps eventually the

breaking up of [polar ice sheets. Although this will be general rise, it will have different local

impacts on tidal and current patterns. A sea-level rise would have devastating impacts in certain

societies, like those of low-lying island nations, or those concentrated in low river deltas. In the

northern region hemisphere, Polar Regions will warm faster than equatorial zones; on the

continental land masses the centers will become drier than the peripheries and so on. There will

be very substantial impacts on ecosystems and individual species of plants and animals, not just

because of the amount of change but because the rate of change will be fast by evolutionary

standards. Many organisms will not adjust to changing habitats, especially species that occupy

narrow ecological niches, because relatively small changes in weather patterns can destroy the

habitats on which they depend. Ecosystem diversity may decline. There may also be major

migrations of species to different climate zones. Malaria and other tropical diseases may become

endemic in more areas of the world. On the positive side, higher concentrations of CO2 in the

atmosphere may enhance the growth rates of plants species Field and Olerwiler, 2011, p. 401). .

The impacts on human will be through the effects of changed climate patterns on agriculture and

forestry.

Scientific Uncertainties and the precautionary Principle: It is sure global warming is

happening and is due to human activity and no policies for reduction or mitigation of

greenhouse-gas emissions should b e introduced. The precautionary principle says that society

should weigh the trade-off between the cost of measures taken today versus benefits in terms of

reduced future risk. Mitigation policies could include the usual array of policy instruments

(standards, taxes, TDPs) plus voluntary actions on the parts of households and producers( energy

substitution, consuming products that are less energy-intensive, creating more carbon sinks, and

so on). Society may incur much higher costs than if actions were taken today to put it on a more

sustainable path that reduces carbon emissions. If society does nothing and turns out to be

wrong, global warning impacts could be devastating for countries that cannot easily adapt.

Equity considerations may suggest taking action now rather than waiting. The role of

technological changes may help to mitigate global warming. A GHG tax at very low rate could

be introduced now with the rate rising over time. Or, tradable permit system could be introduced

with the aggregate number of permits set to decline over time.

Technical responses to the Greenhouse Effect: GHGs mitigating efforts can start with forestall

damaging climate changes in the future. This allows identification of areas where mitigation

policies can be introduced. Total GHGs= Population X GDP/ population X energy GDP X

GHGs/ energy.

Energy efficiency is another point for GHG reduction strategy-the amount of energy used per

dollar of output. The key is here move toward technologies of production, distribution, and

consumption that require relatively smaller quantities of energy.

Policy response- The Kyoto Protocol

The Framework Agreement on Climate change, referred to as Kyoto Protocol, was signed by

many of the world’s countries in December 1997. Ach signatory to the Kyoto Protocol set its

own target for reduction in GHGs to be met by 2008-2012. Each country decides what policies to

use to meet the targets. The protocol is not binding on any country-there is no way to enforce

these targets. Canada announced at the Kyoto Convention that it would reduce its emissions by 6

percent from their 1990 level by the period 2008-2012. Parliament has not ratified the treaty. In

2000, Hague convention discussed complex issues such as whether to give a country credit for its

carbon sinks, rulers for a TDP system. However they did not sort out specific strategies to

mitigate this problem like how to finance adaptation and mitigation measures for developing

countries, what qualities as a carbon sunk; how to define operating rules and procedures for a

tradable permit system; and how to define the nature of the compliance regime.

Why International Agreements Often Fail: Game Theory Application

When the costs and benefits of reducing GHs vary widely across the world a simple game theory

analysis can be applied. Game theory is an analytical technique that helps to show how people

make choices in situations where the outcome of the decisions depends not only on their own

actions, but also on choices made by other people. To make the analysis manageable, assume

there are two countries that are trying to reach an agreement about whether to ratify the Kyoto

Protocol. The principles from the two countries model help describe what appears to be

happening globally with GHGs. Assume that each country can either: emit at current levels

called high emissions; or reduce emissions by 5 percent (``called low emissions``). The pattern

of net payoffs is now characteristic of many international environmental problems. They show a

situation where individual countries, each choosing strategies that are best for it, can bring about

a situation that is worse for everybody. The goal of international agreement is to have countries

commit to the `low emission state, but with no enforcement mechanisms to bind countries to

their commitment the game theory techniques show why the agreements may be meaningless.

Canadian GHG Commitments and Policy Initiatives

Even though Canada has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol, Canadian governments are actively

contemplating `what to do`. Federal and provincial governments have been trying to convince

households and firms to adopt more energy-saving consumption and production through

voluntary actions. Firms registered CO2 reduction plans with the federal government but,

because these actions are all self-reported, there is no way to tell if their stated reductions in

GHGs are actually occurring. No market-based policies have yet been introduced. Individual

provinces have also begun to study ways of mitigating GHGs. Two policies are discussed

below-carbon taxes and transferable discharge permits.

Carbon Taxes: A carbon tax could be levied on the carbon content of all fuels. The tax rate

would be based on the units of carbon per unit of energy. Fuels containing more carbon y=unit of

energy (e.g., Coal) would face higher taxes than fuels producing fewer carbon emissions (e.g.,

natural gas). A number of European countries have introduced taxes based on the carbon content

of fuels. The idea of introducing a carbon tax in Canada has not gone very far in the political

arenas. Reasons are opposition from energy industries and energy-producing provinces, fear it

will adversely affect Canadian industry and low-income Canadians, and so on. Canada has the

third lowest implicit carbon tax, the third highest carbon intensity, and the highest energy

intensity of the countries.

Tradable discharge permit (TDPs): Tradable discharge permit (TDP) systems are receiving

considerable worldwide attention as a potential method of reducing GHGs and increasing carbon

sinks. Companies have already engaged in carbon trading activities even through there is no

official recognition of their actions.

Design issues: How will the permits be allocated?

Permits can be either auctioned or distributed without charge. The following are the types of

TDP schemes under discussion in Canada (and elsewhere). Credit Trading: Credits are given

to polluters from documenting a reduction in emissions. This is called a baseline-and –credit

system. The credits can be sold to other companies to use compliance with regulations. Credit

trading has already occurred in Canada on a voluntary basis. A key issue is how to verify that the

reductions represent actual decreases in emissions from what previously existed. Monitoring of

emissions is crucial to this. The ultimate use of credits will depend on government. Substance

Trading: This approach allows for the trading of permits denominated in units of the polluting

substance. In the case of GHGs, this could be the carbon content of fuels, the nitrogen content of

fertilizers, and so on. In a TDP system of emission trading, there will be an overall limit or cap

on the total quantity of the substance consumed domestically, which means a limit on the sum of

production plus imports minus exports. Emission- Rights Trading: This system limits aggregate

emissions of a GHG from specific sources at the point of release into the atmosphere. Sources

emitting the GHG would have an annual cap on emissions, and permits can be traded among the

sources. This is called a cap-and- trade system. This system would probably be limited to utilities

and large industrial sources.

Biological Diversity: A global problem to the survival of life on earth is the worldwide

reduction in diversity among the elements of the biological system-diversity in the stock of

genetic material, species diversity, or diversity among ecosystem. Biological uniformity

produces inflexibility and weakened ability to respond to new circumstances; diversity gives a

system the means to adapt to change.

The human population cannot maintain itself without cultivating certain species of animals and

plants. The continued vigor of this relationship actually depends on the stock of wild species.

About 25 percent of the prescription drugs in the developed countries are derived from plants.

Wild species of plants constitute a vital source of raw material needed for future medicines. Wild

species are critical for agriculture. The stock of species at any particular time is a result of two

processes: the random mutations that create new species of organisms and the forces that

determine rates of extinction among existing species. Some species go extinct because they are

overexploited. But the vast majority is under pressure because of habitat destruction. This comes

primarily from commercial pressures to exploit other features of the land-logging the tress for

timber or wood, converting the land to agricultural uses, clearing the land for urban expansion,

and so on. The information continued in the global stock of genetic capital has consistently been

underserved.

Canada’s efforts with regard to biological diversity are varied, but involve little in the way of

specific regulation. Canada has no endangered species legislation (Field and Olewiler, 2011).

Canada monitors certain at-risk species, particularly migratory birds. The federal government

contributes to the endangered species Recovery Fund, which involves the World Wildlife Fund

Canada.

Canada is a signatory of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The federal government

has set aside land as protected space, and is investing the creation of more wildlife corridors to

permit migration of species. British Columbia has been active in setting aside land in parks. The

effective maintenance of biodiversity depends on the maintenance of habitats in amounts big

enough that species may preserve themselves in complex biological equilibra. This involves first

identifying valuable habitats and then protecting them from development pressures that are

incompatible with preserving the resident species. Canada has a network of reserved lands that

have been preserved in the public domain in national and provincial parks, wilderness areas,

wildlife refuges, and the like. Land reservation for species preservation is essentially a zoning

approach, and it suffers the same fundamental flaw of that policy: It does not reshape the

underlying incentives that are leading to population pressure on the habitats.

One suggestion that has been made to change this is to create a more complete system of

property rights over genetic resources. At the present time, property rights are recognized for

special breeder stock, genetically engineered organisms, and newly developed medicines.

Habitat destruction and species lost continue to appear. Ultimately, each one of us will have to

decide what sort of world we want to live in. If it is one with diverse and healthy ecosystems,

environmental consequences of economic decisions will need to be assessed.

The destruction of biological diversity is a more subtle global problem, but it may be just as

costly in the long run. Dealing with this problem will require greater efforts to preserve habitat

and develop agriculture that is compatible with species preservation. Effective action will do

something about the incentives that currently lead to species destruction.

Chap.-10: Molly Scott Cato (2009). Green Economics: An introduction to Theory, Policy

and Practice. London Earthscan Publishing.

Green Taxation

A green taxation system would be used strategically to achieve three objectives; a fair

distribution of resources, efficient use of non-renewable resources and the elimination of

wasteful economic activity, whether through production or consumption. To achieve equality

within nations, greens would support changes to inheritance tax and higher rates of income tax;

to begin to redress international inequalities, greens support the introduction of a Tobin Tax on

international speculation in currency values.

Green argues for taxes on commons, whose value should be shared between all citizens: the

primary example is a Land Value Tax, but another example is a carbon tax on the right to pollute

the global atmosphere. Taxes on resources and pollution can be used strategically as resources

become more or less in demand and more or less scarce. Scandinavian experience with resource

taxes and the German experience with taxes on mineral oils and electricity were the consequence

of politically activity by green parties. Because environmental taxes can be regressive, i.e. hitting

the poorer members of society hardest, they need to be combined with welfare measures such as

Citizens’ Income scheme which can be funded from the tax yield.

Health related taxation has always been used to encourage more beneficial lifestyles. Green

taxation is also beneficial to ecosystem. Hence green economists provokes for introduction of

ecotaxes. Theory of green taxation: Taxation serves two main functions: (1). It raises revenue

for governments to spend on public goods and services or to redistribute to bring about a more

equal society; (2) it offers policy makers a chance to influence behaviour, encouraging what they

see as beneficial and discouraging what they consider as destructive.

Green economists refer to this as shifting the burden of taxation from ‘goods’ like useful

employment on to ‘bads’ like pollution (Molly, 2011. P. 158). In the case of environmental

taxation, aviation taxes may cause an increase in the price of flights and hence a reduction in

demand. In Ireland plastic bag tax has introduced, which has intended to generate revenue for an

Environmental Fund to pay waste management and anti-littering projects (Molly, 2011, p. 158).

This is a beneficial environmental impact. The key point for a green economist is that taxation

should be used primarily as an important tool to move towards a sustainable economy. Margaret

Legum defines the objectives of a taxation system as follows: Taxes should encourage social

inclusion, social equality, economic efficiency, and environmental sustainability. They should

discourage the use of non-renewable resources, monopoly of common resources, pollution and

waste. (M. Legum (2002). It doesn’t have to be like this, Glasgow: Wild Goose Publications in

Molly2011, p. 158)). Existing taxes are perverse because they:

Reduce employment by taxing it and value added by it;

Subsidize capital and energy-intensive production;

Encourage pollution and wastes, which are the state then has to repair through the health

services;

Encourage inefficient land use and speculation;

Encourage currency speculation;

Subsidize long-distance transport and hence inefficient use of resources

James Robertson argues that green taxation is ‘predistribution’ rather than ‘redistribution’ and

proposes for sharing of basic resources such as land and housing, which would then reduce the

need for latter redistribution of incomes. Predistribution will be empowering. It will correct an

underlying cause of economic injustice, inequality, exclusion and poverty (J. Robertson (2004).

Using common resources to solve common problems’, Feasta Review 2: Growth: The Celtic

Cancer, Dublin Feasta).

Strategic Taxation: Green economists favour the use of a whole range of strategic taxes to

achieve different aims; redistributing income, encouraging the deconsolidation of large

corporations into smaller businesses, supporting lees polluting forms of agriculture, and so on.

Green economists are deeply concerned about the wide and growing inequality both within

developed economics and between them and the poorer economics of South. They argue that

wealth should be redistributed within developed economics through a range of taxes, the most

fundamental of which is income tax on higher earners. However, green economists are also

concerned with the increasing share of assets owned by a smaller proportion of very wealthy

people. Thus a green economy would likely to be involved distribution of assets and capital gains

taxes.

Tobin Tax is a percentage tax on speculative financial transactions, imposed at the global level

with the revenue invested in projects to improve the lives of those living in poorer nations. The

value of land Tax or Robertson refers to it as ‘Land Rent-Tax’. It is a tax on the annual rental

site value of land. The annual rental site value is the rental value which is a particular piece of

land would have if there were no buildings or improvements on it. It is the value of a site, as

provided by nature and as provided by the nature and as affected for better or worse by the

activities of the community at large. Earth’s atmosphere polluted with green house gases,

causing economic disaster for others, should be paid for with a carbon tax. A carbon tax can be

considered a ‘common tax’, since it attempts to reduce behavior that adds to the amount of CO2

pollution in the atmosphere, which is a shared commons. Such a tax would provide a strong

incentive for both businesses and individuals to reduce their energy consumption, their driving,

and to switch to non-fossil-fuel heating as well as renewable electricity supply. The Swedish

carbon tax achieved a reduction in CO2 emissions of 7 per cent, while the Danish energy tax

resulted in a 10 per cent reduction in energy use ( D. Fullerton, A. Leicester and S. Smith (2007).

Environmental Taxation, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies in Molly, 2011, p. 164).

Ecotaxes: Ecotaxes have two aims: to discourage pollution and to change behavior, especially

behavior that leads to the unsustainable use of non-renewable resources. In the industrial

countries, labors are relatively more expensive and more highly taxed; materials are cheap and

lightly taxed. Green taxation can level the playing field for eco-material vis-a-vis nonecological

products, it can discourage waste, and it can help create an economy that is more peopleintensive than capital-intensive (Milani, B. (2002), Green Designing Economics, p. 195).

Citizens’ Income supports the incomes of the poorest in society.