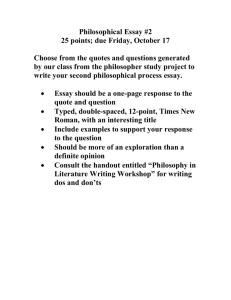

Essay Explication Unit

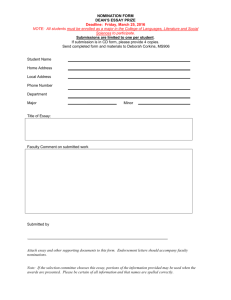

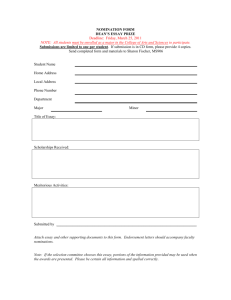

advertisement