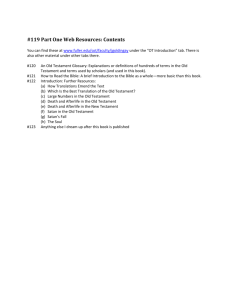

“Interpreting the Old Testament in Baptist Life”

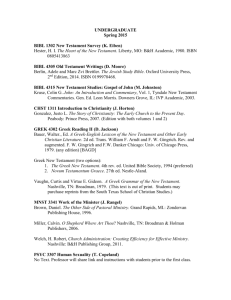

advertisement