Reading Edited Texts

advertisement

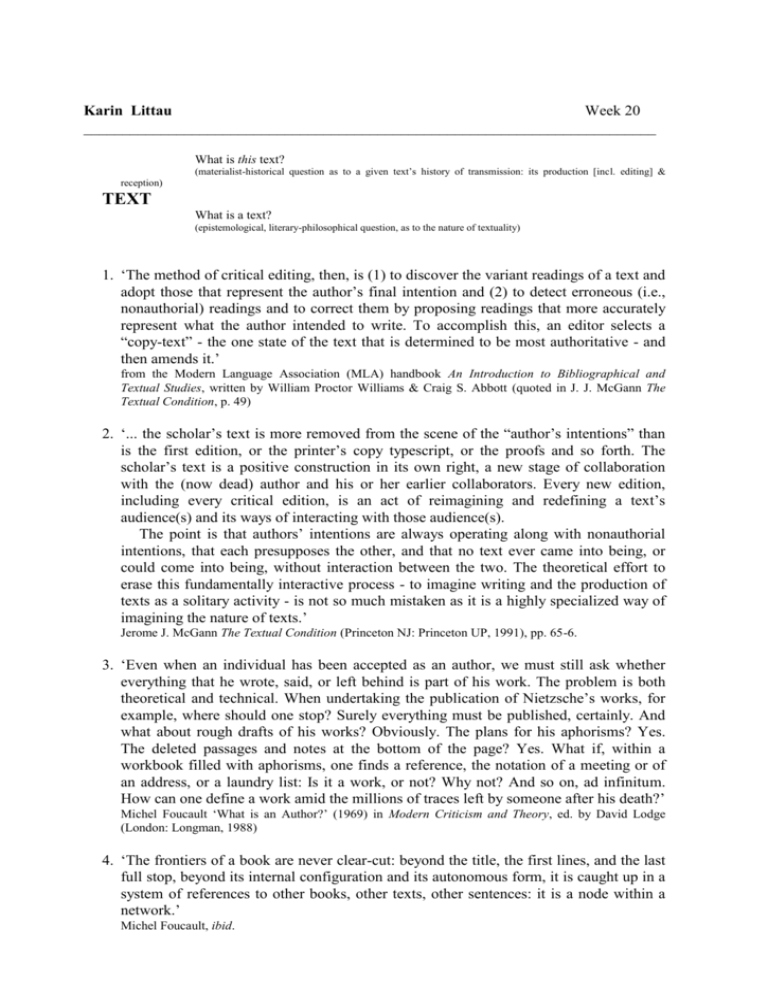

Karin Littau Week 20 __________________________________________________________________________ What is this text? (materialist-historical question as to a given text’s history of transmission: its production [incl. editing] & reception) TEXT What is a text? (epistemological, literary-philosophical question, as to the nature of textuality) 1. ‘The method of critical editing, then, is (1) to discover the variant readings of a text and adopt those that represent the author’s final intention and (2) to detect erroneous (i.e., nonauthorial) readings and to correct them by proposing readings that more accurately represent what the author intended to write. To accomplish this, an editor selects a “copy-text” - the one state of the text that is determined to be most authoritative - and then amends it.’ from the Modern Language Association (MLA) handbook An Introduction to Bibliographical and Textual Studies, written by William Proctor Williams & Craig S. Abbott (quoted in J. J. McGann The Textual Condition, p. 49) 2. ‘... the scholar’s text is more removed from the scene of the “author’s intentions” than is the first edition, or the printer’s copy typescript, or the proofs and so forth. The scholar’s text is a positive construction in its own right, a new stage of collaboration with the (now dead) author and his or her earlier collaborators. Every new edition, including every critical edition, is an act of reimagining and redefining a text’s audience(s) and its ways of interacting with those audience(s). The point is that authors’ intentions are always operating along with nonauthorial intentions, that each presupposes the other, and that no text ever came into being, or could come into being, without interaction between the two. The theoretical effort to erase this fundamentally interactive process - to imagine writing and the production of texts as a solitary activity - is not so much mistaken as it is a highly specialized way of imagining the nature of texts.’ Jerome J. McGann The Textual Condition (Princeton NJ: Princeton UP, 1991), pp. 65-6. 3. ‘Even when an individual has been accepted as an author, we must still ask whether everything that he wrote, said, or left behind is part of his work. The problem is both theoretical and technical. When undertaking the publication of Nietzsche’s works, for example, where should one stop? Surely everything must be published, certainly. And what about rough drafts of his works? Obviously. The plans for his aphorisms? Yes. The deleted passages and notes at the bottom of the page? Yes. What if, within a workbook filled with aphorisms, one finds a reference, the notation of a meeting or of an address, or a laundry list: Is it a work, or not? Why not? And so on, ad infinitum. How can one define a work amid the millions of traces left by someone after his death?’ Michel Foucault ‘What is an Author?’ (1969) in Modern Criticism and Theory, ed. by David Lodge (London: Longman, 1988) 4. ‘The frontiers of a book are never clear-cut: beyond the title, the first lines, and the last full stop, beyond its internal configuration and its autonomous form, it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network.’ Michel Foucault, ibid. From Jerome J. McGann, The Textual Condition (Princeton NJ: Princeton UP, 1991) a) ‘Everyone agrees, of course, that meaning is a wild variable, but people also commonly assume that the “originals” do not vary, or (perhaps) that they vary at a much slower rate. Once the words are set down on the page, we imagine them as fixed for good always understanding, of course, that physical deterioration may erode such fixity over time. In this view we see texts as relatively stable, whereas interpretation is sowing the wind. But the fact is that interpretation is an act which gets carried out only as a response to a given textual condition. We say that two interpreters of a particular text “read” it differently because they are not seeing the same “text”, because they have imagined their interpretive object differently. In our own day, these interpretive differentials are ordinarily ascribed (inscribed) to the authority of readers, who make meanings according to what they imagine to be most interesting or useful or marketable. The meanings, in this scenario, are imagined to originate in readers, who translate and reimagine the passive texts that come under their hands. This fairly recent way of thinking about meaning has displaced altogether the common, earlier way. The latter conceived the interpreter as one who set out in quest of the meaning of the text. Interpretive variation, in such a case, need not be a sign of the interpreter’s constructive or creative activity (though it could be that); rather, it signalled, characteristically, the failure of the reader to penetrate to the whole truth of the text. The extreme variability of midrashic interpretations of the bible is the (paradoxical) sign of this approach to reading a text: the Word of God is One, like its Truth, though the words of men are many, like themselves. Let me point out, however, that in each of these interpretive theories, the stability of the material text - the interpretive location, or material object - is assumed. On the contrary, however, what I am arguing here is that no such stability in the material object can be assumed with respect to texts. [...] if we define a text as words in a certain order, then we have to say that the ordering of the words in every text is in fact, at the factive level, unstable. No text, either conceptually or empirically, can have the “ordering of its words” defined or specified as invariant. Variation in other words, is the invariant rule of the textual condition. Interpretive differentials (or the freedom of the reader) are not the origin or cause of the variation, they are only its most manifest set of symptoms.’ (pp. 184-5) b) ‘The textual condition’s only immutable law is the law of change. [...] Every text enters the world under determinate socio-historical conditions, and while these conditions may and should be variously defined and imagined, they establish the horizon within which the life histories of different texts can play themselves out. The law of change declares that these histories will exhibit a ceaseless process of textual development and mutation - a process which can only be arrested if all the textual transformations of a particular work fall into nonexistence. To study texts and textualities, then, we have to study these complex (and open-ended) histories of textual change and variance. But texts do not simply vary over time. Texts vary from themselves (as it were) immediately, as soon as they engage with the readers they anticipate. Two persons see “the same” movie or read “the same” book and come away with quite different understandings of what they saw or read. Do not imagine that these variations are a simple function of differentials that reside “in the readers”: in personal differences, or in differences of class, gender, social, and geographical circumstances. The differences arise from variables that will be found on both sides of the textual transaction: “in” the texts themselves, and “in” the readers of the texts.’ (pp. 9-10)