THE SOCIO-CULTURAL EFFECTS OF THE LANGUAGES OF

advertisement

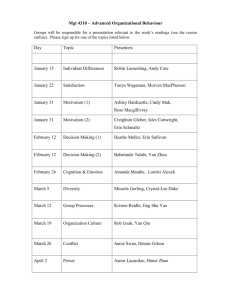

Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde THE SOCIO-CULTURAL EFFECTS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AFRICA TO THE INTEGRATION OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENT BY DR. SOLA TIMOTHY BABATUNDE Department of English, University of Ilorin, Ilorin. INTRODUCTION An examination of the linguistic map of Africa is the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) revisited. The linguistic terrain of Africa is complex in its multilingualism. Africa is said to have about 2000 languages spoken as first languages by about 500 million people. More than 1 million people speak less than 100 of these languages. If the paramount place of language for purposeful human interaction is considered, then the crisis in the linguistic map of Africa becomes very obvious. However, before we paint the interesting linguistic landscape into details, the expression “integration of the African continent” needs to be defined. Alexandra (1968) defines national integration as the “creating or strengthening within the borders of a country a collective sentiment of belonging together irrespective of individual or subgroup differences”. Bamgbose (1991:10) sees integration as ensuring the “oneness” of a state; “forging as a bond of belonging together as nationals of the state”. Since colonialism has bequeathed the legacy of artificial nation-state to Africa, a major pre-occupation of African leaders has been the creation of a bond between the citizens to reinforce the sentiment of oneness. Das Gupta for instance, said the following in 1968: Most new nations are based on a plurality of segmental groups. The natural tie of the people to their segmental group is often valued more highly than their civil ties with the nation.(1968:19) Our contemporary experience shows that this is not only true for Nigeria but for the whole of Africa. So the leaders have been preoccupied with both nationism and nationalism. Nationism addresses political integration, while nationalism is concerned with socio-cultural integration. And so in a situation where virtually each language is associated with an ethnic group, fostering a sense of belonging together then looks like an onerous task. A lot of lip service is paid to the need for nationism and nationalism in all African states, but only a handful genuinely make serious and sacrificial efforts to achieve these. For instance, section 15(4) of the 1979 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria states that: The state shall foster a feeling of belonging and of involvement among the various peoples of the Federation, to the end that loyalty to the nation shall override sectional loyalties. This statement rightly sums up the concern for and the preoccupation with integration in African States. Some of the overt strategies of achieving national integration include the use of symbols of unity such as the national flag, a national ruler, a national anthem, a national pledge, a national ideology and of course a national football team (any sportsman who wears the national colours is identified only as a Nigerian, no one regards his tribe at that point). The military especially, is seen as an epitome of this integration. No wonder there is a spate of moves to have a standing African Peace Corps or something like that. These are all seen as symbols of national integration. Other measures usually put in place to ensure national integration include power sharing, multi-ethnic political parties, youth service scheme and all other forms of national ideologies. 1 S.T. Babatunde However, the fact that underdevelopment, poverty and ethnic and tribal conflicts are still prevalent in African states is a testimony to the fact that those symbols and measures have still not helped to achieve integration and development in Africa. The preoccupation of this speech is to investigate the place of the numerous languages of Africa in obstructing national integration, and how language as a crucial gift of God to man can stop being a liability and thus become an asset. It is thus worthwhile at this point to study the linguistic map of Africa. THE LINGUISTIC MAP OF AFRICA The linguistic map of Africa reveals a rich deposit of language resources all over the continent. It is the case of extreme linguistic heterogeneity and cultural plurality. It is a great potential for revealing and articulating the enormous wisdom in the African mind and exploiting these for the transformation of the continent into a haven. Let us now look at this map rather closely. (PLEASE SEE APPENDIXES ONE TO THREE) The scenario pointed above frankly smacks of confusion, the Tower of Babel reenacted. This has given rise to the phenomenon of language problem in Africa. Since problems are difficulties, hindrances and impediments, obstacles in the way of an individual, it is thus easy to understand why language problems are seen as crucial aspects of national and continental problems in Africa. Examining national and language problems in Africa, Babatunde (2003:203) submits that three postures are identifiable: (a) Insensitivity to the existence of national problems; (b) Lack of agreement on what the problems are; and, (c) Lack of agreement on solutions to the problems; In various degrees, this sums up the condition of African states in terms of their consciousness of their condition, and consciousness affects what solutions are proffered for the malady and the degree and speed and extent of healing achieved. Kembo-Sure (2000:1) argues that language is experienced as a problem not in the aspect of meeting the people’s immediate communication needs, but If we think a little more deeply about language and its role in society and the lives of people, we discover that language can indeed be a problem. Language becomes a problem if it is manipulated to perform negative social, political and cultural functions, e.g. when people are denied access to information, people are coerced into speaking a particular language, or killed for speaking a particular one. The performance of negative functions is seen in this lecture as one important part of the socio-cultural effect of African languages, so we shall now examine the effects into details. THE IMPLICATIONS OF MULTILINGUALISM IN AFRICA Multilingualism is like a curse to Africa because it is a liability and not an asset. For clarity, the areas where multilingualism acts as a liability are put into five categories of social, political, cultural, psychological and educational. (a) Social The effects of dense multilingualism are heavily felt in the society in the areas of social criteria and social mobility, loss of identity and social conflict Adegbija 1994:45) submits that Most human beings do not enjoy being stagnant status-wise. There is always the quest for higher grounds, higher positions and upward social mobility. A rise on the social vertical ladder has the tendency of boosting 2 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde personal egos. Besides the individual desire and pressure to achieve, there is also the social esteem of those considered as achievers. Language plays a crucial role in ensuring social mobility. However, in the situation where horizontal communication at inter-ethnic, inter-tribal, inter-regional and inter-national levels is denied through plurality of languages, social and mobility also becomes impeded. The masses do no possess the linguistic denominator for social growth; as such they become socially, and of course, economically stagnated. Where there is a semblance of mobility, what we have is vertical mobility of the priviledged few. Not a combination of horizontal and vertical, where the masses of the people are developed. It is common in most African settings to see a star emerging in the midst of darkness – how much light can this provide? One rich man in the midst of six poor people is also very poor. The incidence of social inertia gives rise to all kinds of poverty-induced violence; e.g. armed robbery, hired killings, and all kinds of organized crimes. This also explains why the few ones at the top of the social ladder are always afraid of falling. They are not comfortable at the top because the societal structure sustaining them is artificial and unstable. Any slight tremor or stress brings it crashing down. A rich man in any African state today can become the poorest person around the next couple of years. Large scale money laundering, sit-tight leadership, self-succession and all other kinds of corrupt practices cannot provide insurance against poverty. Language usage is also seen as a means of projecting social identity. So any attempt made to kill a man’s language becomes a mode of obliterating his identity. The situation whereby a language becomes a primus inter peers (first among equals),the speakers of the other languages feel their identity is being eroded. (b) Psychological Extreme multilingualism in Africa also has effects on human behaviour. Language constrains people to think in a particular way and their perception of language determines their attitude to the languages in the society. Indeed, the attitude one has to a particular language, either MT, L2 or any other language in the environment, determines ones attitude to the speakers of the language. The languages in a nation can be put into four categories for stream-lining in discussing attitudes to them and for facilitating planning (Babatunde and Olujide, 2003:209). These are major, minor, official and foreign. In African states, the speakers of major languages tend to look down on other languages; whereas the speakers of the minor languages feel look at the major languages with suspicion. The minor languages speakers always look out for the signs of exploitation and oppression in the conduct of the major languages speakers. There is therefore a constant struggle for supremacy and survival. This situation is antithetical to growth and development. The speakers of a language also tend to have an unusual attachment to and affinity with their language and tribe to the exclusion of other tribes and tongues. This breeds a high level of suspicion and distrust on one hand, and undue, almost illogical love on the other. Again, this attitude does not allow for meaningful inter-ethnic and inter-tribal collaboration capable of engendering progress and development. Various ethnic and tribal leaders all over the continent to bring about inter-tribal wars have exploited this tendency for excessive attachment to ones language and tribe. In Nigeria, for instance, what clear-minded justification do we have for groups like OPC, Ndigbo, ACF, Afenifere and other militia groups in the Delta region? This scenario is replicated all over Africa. The ex-colonial languages have the status of official languages in most African states. These languages, English, French and Portuguese, are promoted with the misconception that they are the only languages to enhance social climbing and foster inter-ethnic cohesion. Research on language attitudes 3 S.T. Babatunde (see Adegbija, 1994, Babatunde, 1998 and Bamigbose, 1991) show that Africans have an ambivalent attitude to these languages; i.e. a love-hate attitude: Love for its functions, and hatred for its history and its adverse effects on the indigenes. The intensive multilingual set up has also given the foreign languages the air of irrelevance. So many indigenous languages struggle for attention and relevance, thereby pushing languages like French, German and Russia in Nigeria to the back seat. This of course is not a psychological context for integration and development. (d) Cultural Hammerly(1982, Quoted in Rubanya (2002:45) defines culture as a “ broad concept that embraces all aspects of the life of man, that is the total way of life of a people.” Culture is said to be divided into three types: informational, behavioural and achievement. Rubanya explains further: Informational refers to what the natives know about their society. This should be part of the language of a particular society… Behavioural culture is basically conversational formulae and kinetics which are most important to successful communication. … Artistic and literary achievements are important cultural accomplishments in society.(pp 45-46). The relationship between language and culture has been of utmost concern. Despite some degree of argument on which determines and influences the other, there seems to be a measure of agreement on the fact that, Language can be considered as cultural practice, and that language is both an instrument and a product of culture. This would mean that … the Baluhya and Luo of Kenya use languages that are historically products of distinct cultures, but which are increasingly used to express the same cultural reality. This has been the result of extensive interaction that has caused cultural convergence between linguistically different groups. (Ndoleriire, 2000:272-273) Mazrui (1990) opines that culture performs seven functions: gives people the means of perception and cognition, motives for behaviour, criteria of evaluation, a basis of identity, a mode of communication, a basis for stratification, and a system of production and consumption. This clearly subsumes language under culture. It is a result of this view and that expressed by Duranti (1997) that Ndoleriire submits that the interrelationship between language and culture involves the following: individual people learn the values, norms, beliefs, views and behavioural patterns … of the group or groups of which they are members through linguistic interaction; groups give expression to their cultural identities, and practice their cultural life, not only through music, art, dancing, and dress, but also through language; and language reflects the cultural character of people both in their vocabulary… and in their discourse conventions and ways of speaking (p. 274). With this background on language and culture, a number of effects of the African languages on culture can be identified: Firstly, multilingualism results into cultural plurality and since this is not explored to give rise to a rich cultural knowledge for an individual, it results into inter-tribal misunderstanding and misconception. This provides the necessary background for disunity and strife. Closely related to culture-induced conflict is cultural alienation, which arises because of the imposition of other languages on the people. The greatest culprits here are the ex-colonial languages. Africans are then made to have an unduly high opinion of European languages and cultures and a resultant low opinion of the indigenous languages and culture. This leads to language shift, 4 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde enculturation and eventual language death for the indigenous languages. Webb and Kembo-Sure (2000:13) define language shift as a process in which he speakers of one language begin to use a second language for more and more functions, until they eventually use only the second language, even in personal and intimate contexts. Language shift becomes total when the second language becomes a symbol of the sociocultural identity of these speakers. Language death therefore is when all the speakers of a particular language no longer use their language, for active social interaction, such that no one is left who still speak “the original language as a first or primary language”. Language shift leads to culture shift and cultural alienation because the people whose language has shifted seem to lose direction. Let us listen to Lawino speak to Ocol in Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino (1966): My husband pours scorn On Black People He behaves like a hen That eats its own eggs A hen that should be imprisoned Under a basket… He says black people are primitive And their ways are utterly harmful Ocol says he is a modern man A progressive and civilized man … (pp 35-36) …Listen Ocol, my old friend The ways of your ancestors are good, Their customs are solid And not hollow They are not thin, not easily breakable, They cannot be blown away by the winds Because their roots reach deep into the soil… Listen, my husband You are the son of a Chief. The pumpkin in the old homestead Must not be uprooted! (p. 41) The Ocols of Africa refuse to heed this warning, and as such the uprooting of African cultural heritage has led to the uprooting of his personality. He is now tossed about by the wave of the wind. Cultural rubbish from the West finds a ready abode on the continent! This cultural alienation has given rise to poverty and crime. Nowadays many Africans are cultural mullatos – they are neither here nor there. This is the case of cultural abdication, and they thereby become misfits. We are neither fully accepted by the West (and those who go there frequently can testify to this), neither can we confidently fit into our cultural ambience. A neglected language and culture soon becomes extinct and this has grave implications for loss of identity, loss of personality and loss of societal control and order. May God deliver us! We can now discuss the political effects of multilingualism in Africa. (d) Political The adverse effects of complex multilingualism appear to be more felt and volatile in the area of politics than elsewhere. When languages become identified with particular political philosophies or 5 S.T. Babatunde programmes, and as such invested with particular political meanings, they are said to be politicized (Webb and Kembo-Sure, 2000:16). In Nigeria, we can talk of the micro and macro features of this phenomenon; e.g. “Yonmirin”, “Kobokob”, “ngbatingbati”, “mala”, etc, on one hand, and Afenifere, Ndigbo, Ohaneze, Arewa, etc. These expressions have great political implications which can be derogatory, divisive or uniting, as the case may be. This phenomenon can be replicated all over the continent, and they thus become symbols of ethnic intolerance and disunity. Expressions like Boers, rooinekke (red necks), kaffirs, coolies, boesmans (Bushman) and san (tramp) have serious ethnic and tribal connotations in South Africa. Another common political effect is the politicization of some language-related phenomenon like language learning and teaching, ethnicity and the like. The players in the political terrain often for negative effects manipulate these. Eventually, the masses of the people are denied political knowledge because of access to the dominant language of politics, thereby resulting into low and inadequate participation in politics and national development. We should also mention the implications of the administrative aspect of the politics of language. Bamgbose (1991:111) submits that a common feature of multilingualism and language planning in sub-Saharan Africa is “avoidance, vagueness, arbitrariness, fluctuation, and declaration without implementation”. This attitude of government is partly caused by ignorance, instability and lack of continuity of the administrative and political machinery. In other cases, the political leadership does not demonstrate seriousness and commitment in finding solutions to daunting national language problems. The outcome of politicization and administrative negligence is instability in the nation. This is why integration (at the national and continental levels) has been a problem in Africa. Nigeria has witnessed such earth-rending crises within the last fifteen years or so, and each of these is enough to finally tear the nation to shreds. The David Orkar coup of April 1990 failed partially because of the articulation of ethnic hostilities. If we move to the West Africa sub-region we can easily identify the ethnic genesis of the crises in Liberia, Sierra-Leone, Togo and Chad. This is the description of what the situation is in the continent. These crises result into great losses in human, material and spiritual resources. These resources should have been harnessed for growth and development. (e) Educational Politicization of language and the neglect of the indigenous languages in Africa result into a tremendous incapacitation of the populace. The colonial languages are still predominantly used for formal education in African states. As far as competence in these languages is concerned, many learners are not adequate in the languages to the point of effectively acquiring knowledge in them. Learners are not only grappling with the second language, but also struggling to learn in them. Apart from this, several varieties of these colonial languages are in use all over the world, e.g. the English language. Knowing which variety to realistically serve for teaching and learning can be a very serious problem. Babatunde (2002:69-95) examines the trend in world Englishes and the paradox in the teaching of the English language in Nigeria. Using the senior secondary school as case study, he submits that “The target variety of English language in Nigeria is amorphous… and this is an unhealthy condition in a pedagogical context” (p.92). The primacy of the mother tongue (MT) for educating the child has been long established. The MT or first language (L1) plays a major role in moulding the early life of the child and it is the means of orientation in the cultural environment. As such, using it in educating the child “in the first years of schooling enhances continuity in the child’s learning process and therefore maximizes his intellectual development”. (Chumbow, 1990:63) On the other hand, refusing to use it for initial learning is denying opportunity for rapid/accelerated and easy acquisition of knowledge for the child. Many dropouts very early in their learning career thus giving rise to mass illiteracy, poor development of the educational system, limited and lack of access to knowledge and skills. 6 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde Having outlined the effects, what then can be done to practically transform these obstacles to the facilitators of the integration of Africa? LANGUAGE AS MIDWIFE FOR INTEGRATION IN AFRICA Language is so important to men that anyone without a capacity for language use and usage is at best in a partial existence. This means that efforts in developing language and solving language and language-related problems in the society are efforts in the right direction for the complete development of such a society. The resources associated with language are enormous and these should be adequately tapped for unity and progress. For clarity, a summary of the functions of language should help to illuminate the point being expressed here: Language, for instance, functions in public domains of life, as instruments of learning, instrument of economic activity, social mobility and other serious public business. Henceforth, we shall enumerate the midwife role of language for integration in Africa using the two perspectives of attitude and sociolinguistics. (a) Attitude It is evident from the foregoing that attitudinal misconceptions are largely responsible for the negative roles of language in national integration. Bamgbose (1991:15) submits that “it is not language that divides but the attitude of the speakers and sentiments and symbolism attached to the language”. Bamgbose also quotes Fishman (1968:45) where he (Fishman) opines that Differences do not need to be divisive. Divisiveness is an ideologized position and it can magnify minor differences; indeed it can manufacture differences in language as in other matters almost as easily as it can capitalize on more obvious differences. Similarly, unification is also an ideologized position and it can minimize seemingly major differences or ignore them entirely…. As a result, attitudes to language must change in the following areas: (i) Individual’s extreme attachment and loyalty to MT must change in a multilingual context. This enables people to respect and regard speakers of other languages in the environment – whether major or minor languages. It also prepares the ground for the individual to be effectively multilingual. (ii) Language, though a means of defining and recognizing identity should be seen as a tool, a means. It is not an end in itself; it is a means of getting to that end. As such, any language is capable of being used as a means to this perceived end. It is only crucial that the necessary contextual features capable of making the language to function adequately be provided (see Adegbija, 1994). (iii) There must be mutual respect and recognition for all the languages in a multilingual context. This is without prejudice to whether such languages are Languages of Wider Communication (LWC) Major, Minor, Official languages, etc. The languages have come to stay and their presence should be properly utilized for the provision of the resources necessary for unity and progress. Government should therefore make policies that will portray this attitude and ensure the development of the nation. The present situation where a few priviledged languages are developed and used has served only to train a small group of elites to run a bureaucracy and the modern sector of the economy while neglecting the training of human resources capable of stimulating production in areas essential to the welfare of the majority of the population (Raymaekers and Bacquelaine, 1985:455) (iv) Attitude change is also needed in the proper perception of the MT or a child’s L1 in facilitating his intellectual development. A number of initial learning projects using the MT have proved that their use avoids regression in the child’s acquisition of knowledge and 7 S.T. Babatunde (v) skills. We, for instance, have the Rivers Readers Project, the Six Year Primary Project (Yoruba) and the Karatu project in the Plateau area. We also need a change of attitude in the hegemonic status of the colonial languages of dominations. Adegbija for instance submits that: It is generally assumed by many people in sub-Saharan Africa that implanted European languages and cultures are inherently superior for education (p.104). Apart from their assumed superiority in education, their users are also considered to have a higher social standing. This must change because no language is superior to the other, and a language can develop only if it is used for communication in all the spheres of human endeavour. (vi) Another misconception is the tendency to see these European languages as emblems of national unity and integration. This is because they are not the MTs of anyone in Africa, so no one is likely to frown at their widespread use as official languages. Experience has however shown that when the chips are down, people forget the European languages and quickly use their MTs for in-group communication. We therefore must be pragmatic and then look elsewhere (or is it within?) for the solution to the problem of integration in Africa. (b) Sociolinguistic Measures Aside of attitudinal changes, certain practical steps must be taken to revamp the ailing status of African languages and situate them in the right position for fostering continental integration. These steps will engender a process. i) The first step has to do with the formulation of realistic language policies. African nations have many policy options, which are capable of changing the linguistic terrain towards the desired direction for unity and progress. There are some basic differences in the situation in each country, as portrayed in the linguistic map of Africa. There are also differences in the philosophy of the government in each country. These differences necessitate the use of different policies. A policy, which works in a country, may fail woefully in another one. Somalia and Tanzania, for instance, aggressively promoted their national languages with a high level of initial success. This certainly will lead to deep crises in other African countries, e.g., Nigeria. For such a policy to work there must be a strong or revolutionary government and a strong population base for whatever languages are declared as national languages. The third condition is the political will and mobilization of the populace to support such a policy. Where these three conditions are not satisfied, having a revolutionary language policy becomes a reckless act with grave sociopolitical consequences for the nation. This is why the promotion of Swahili in Kenya has not met the kind of success initially recorded in Tanzania. Political instability and other factors have eroded this initial success (see Rubanza 2002:39-51). ii) 8 A sincere and realistic move to take decisions on the linguistic terrain of a nation has the privilege of receiving inputs from the following activities: sociolinguistic surveys, descriptive studies, pilot projects, commission, conferences, and resolutions by international organization. These sources of input provide a nation with a broad-based objective data for decision-making. It also has a way of involving experts and other interest groups in the decision-making process in a meaningful way. Babatunde (1998) proposes a framework of language evaluation capable of achieving great success in a multilingual context. (SEE APPENDIX FOUR) Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde The scheme recognizes the need to consider the numerous contextual issues in a particular situation. These contextual variables provide input which act as background for the classroom implementation of the policy. This scheme recognizes the place of the classroom, the school system, in the successful implementation of a language policy. The scheme has in-built devices for evaluating the product of this policy implementation. It is important to observe that though it is government that takes policy decisions, planning cannot be left to government agencies alone. Sincere efforts must be made to have a comprehensive plan which gives due recognition to all levels of decision-making; including of course, giving due roles to non-governmental agencies. Babatunde’s framework above provides opportunity for this. Three approaches to the national language question are identified by Bamgbose (1991). These are: status quo, radical and gradualist. The status-quo approach looks at the many socio-cultural problems in a nation and considers it overwhelming. The reluctance to add the efforts on resolving the national language problem thus makes such a nation to be satisfied with the status quo. Usually, the status quo has the ex-colonial language as the dominant one for official communication. For such a nation, any language will do as long as intra and international communication is facilitated. Needless to say, such an approach is superficial because it ignores “the claims to sentimental attachment and authenticity. The continued use of a foreign official language will leave the gap between the elites and the masses as wide as ever.” (Bamgbose, 1991:32) The radical approach explores the sentiment of nationalism and insists on addressing the national language question with immediate effect because it is rightly seen as the rallying point for the nation and a definer of nationhood. The leadership insists and it often persuades or even coerces the populace to agree. We mentioned the Tanzania and Somalia examples earlier. Experience has shown that this is unrealistic because a change in leadership always witnessed a change in focus and philosophy in Africa. So, the next government may not have the will to continue with such a radical national language policy. The gradualist approach reaches a compromise between the status-quo approach and the radical approach. A foreign language is allowed to continue to serve as the official language while steps are taken to promote indigenous languages to the status of being used in all areas of communication in a nation. This approach takes a long-term view on the matter and institutes decision implementation logistics within the plan (Adegbija, 1994a: 160). Experience has shown that this gradualist approach is the most viable for African states. (Adegbija, 1994a: 161) refers to this as an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary approach. He adds that Given the complex network of contextual profiles in African multilingual settings, it would seem, in most cases and to a large extent, that evolutionary, rather than revolutionary language planning changes would have greater promise for effectiveness. The holistic nature of sound language planning has been recognized (see Williams 1991:315). This is why any serious language-planning proposal must be very comprehensive so as to accommodate all the interest groups and confront all identified problems to the success of a language planning decision. To this end, we shall present Adegbija’s (1997:17-24) proposal for rescuing the indigenous languages from strangulation, and for subsequently facilitating the integration of Africa. Adegbija (1997) has a five-step proposal, which includes: a. A strong, basic commitment and developmental philosophy b. The establishment of national and local language-development coordinating bodies, committees, or agencies c. Deep involvement of the language communities concerned in development efforts 9 S.T. Babatunde d. Tapping all available resources and reducing language-development costs; and e. Official institutionalization of multilingualism. So far, we have seen that a gradualist or evolutionary approach that is holistic and comprehensive in nature will suffice in solving the continental language and integration problem. iii) Let us argue further by submitting that contemporary reality and sociolinguistic research in Africa point to linguistic harmonization as the panacea for the plurality and disunity that are languageinduced in the socio-political terrain. Linguistic harmonization, as discussed by Prah (2002:1) involves the introduction of “order in the confusion of the linguistic classification on the basis of mutual intelligibility: for speech forms and dialects, or variants of larger linguistic entities.” A lot of work is going on in the continent of the rehabilitation of African languages. Much of this is being done under the auspices of the Centre for Advanced Society (CASAS). Rehabilitation has been chosen as the way of delivering African languages (and indeed Africa) from the thrones of relegation and perpetual retardation and death because, Africans learn best in their own languages, the languages they know from their parents, from home. It is in these languages that they can best create and innovate. Such innovation and creativity are crucial, not only for development in an economic sense, but also necessary for the flourishing of democracy at a cultural level; they are the languages, which successfully engage the imagination of mass society. It is in these languages that the culture and the histories of African People from time immemorial have been constructed. It is in these languages that knowledge intended for the empowerment of the larger masses of African society can be affected. (Prah, 2002:1). There are reports of success in H.B.C Capo’s pioneering work on Gbe languages of the West African sub-region. Work in West Africa is also focused on the Gur, Bambara, the Akan, the Yoruba and the Edoid clusters. Work is also in progress on the harmonization of the Bantu languages of Central Africa, and Zimbabwe and Mozambique have also been included. The Khoisan languages are also been harmonized and standardized. Progress on the non-Khoisan languages is being impeded because of the absence of native speakers with specialist linguistic training. Presently, there are illuminating and exciting reports on progress made in such countries as South Africa, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Ivory Coast, Central and Eastern Africa. The problems encountered are highlighted, discussed and solutions proffered. These moves are exciting, to say the least, and they sing the sonorous tune of hope for the future. It is however needful to observe that the work being done is largely by non-governmental organizations, individuals, and western agencies, like the Ford Foundation. African governments still demonstrate a low level of awareness of the need to solve the problems. Their readiness to implement the results of these research efforts is therefore very doubtful. An improved level of commitment and involvement is urgently needed. However, it cannot be over- emphasized that harmonization and standardization of African languages by its nature ensures cross-cultural, inter-ethnic, cross-regional, international and continental interaction and interrelationship. To this end, it insists that collaborative efforts go on across the continent thereby laying a firm foundation for integration. Also, harmonization and standardization recommend the development of terminologies, translation of reading materials into indigenous languages, production of written literature in indigenous languages, the development of meta- languages, raising of the consciousness of the people towards languages, production of pedagogic materials for indigenous languages and the teaching of initial literacy in the indigenous languages. The implication of this is that a literate environment is created and ignorance is largely eradicated. 10 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde Any development effort, which is not concentrated on total human development, is at best a scratching of the matter on the surface. Total human development emphasizes the “full realization of the human potential as a maximum utilization of the nation’s resources for the benefit of all” (Bamgbose, 1991:44). Bamgbose argues further that The primary causes of poverty are really deficiencies in education, organization and discipline. It is these, rather than goods, that can stimulate development, as can be shown by economic miracles achieved by countries without material resources but with the crucial factors of education, organization and discipline intact. (44) The best way to achieve total human development therefore is through functional literacy; and, it is much easier to achieve this using the first language of the pupil. Harmonization provides a shortcut for achieving this objective; it creates a literate environment and enhances participatory democracy. Literacy banishes ignorance and provides the condition for wealth. The poor are often used as canon fodders by the perpetrators of disunity and confusion because they are poor, ignorant and hopeless. Their total development thus delivers them from being used as instruments of destruction. CONCLUSION We shall end this speech by simply exhorting us to be personal and inward looking. Charity they say begins at home. We need to ask ourselves about the role we can play in ensuring integration in Africa vis-a- vis our attitudes to our indigenous languages and the ones around us. Here are some highlights: Attitude change Personal and Family language policy Deliberate Bi- multilingualism If we give a liberal approach to information, and relate adequately with our neighbours without undue tribal or ethnic sentiments, we have taken the first steps towards integration. It is cheaper to prevent conflict than to resolve them. You are in a better position to understand this. 11 S.T. Babatunde BIBLIOGRAPHY Adegbija, E.E. 1993 “The Graphicitation of a Small Group Language. A Case study of Oko”. International Journal of the Sociology of Language102,153-173. Adegbija, E.E. (1994a) “The Context of Language Planning in Africa. An Illustration with Nigeria”. In Martin Putz ed. Language Contact Language Conflict Amsterdam: John Benjamin’s B.V. Adegbija, E.E. (1994b) “Applied Linguistics: The Need of Africa. Paper presented at the Southern African Applied Linguistics Association (SAALA) 14th Annual Conference, 28 June – July 1994. Adegbija, E.O. (1997) “The Identity Survival, Journal of the Sociology of Language 125, 5-27. Adesina (1984) Growth Without Development Inaugural Lectures. Faculty of Education Unilorin. Allardt, E. (1973) Individual Needs, Social Structures and Indicators of National Development In S.N. Eisenstadt and Stein Rokkan (ads) (1973a). Building states and Nations, Vol. 1. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. Babatunde, S. T.(1998) An Evaluation of Senior Secondary School English Language Curriculum in Nigeria. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of Ilorin. Bamgbose, A., Banjo, A. and Thomas, A (eds) (1995) New English: A West African Perspective Ibadan: The British Council. Banjo, A. (1994) On Citizenship in a Multilingual State. In Asein S.O. and F.A. Adesano (eds). Capo, H.B.C. (1992) Let Us Joke Over It Nigeria As A Tower of Babel. Inaugural Lecture (44th) Faculty of Arts, Unilorin. Chumbow, B.S. (1990) ‘The Place of the Mother Tongue in the National Policy of Education’ in Emenanjo, E.N. (ed) (1990) Multilingualism, Minority Language and Language Policy in Nigeria. Agbor: Central Books and Linguistics Association of Nigeria, 61-72 Elugbe, B.O. (1990) National Language and National Development in Emenanjo, E.N. (ed) (1990) Multilingualism, Minority Language and Language Emenanjo, E.N. (ed) (1990) Multilingualism, Minority Language and Language Policy in Nigeria. Agbor: Central Books Limited in Collaboration with the Linguistics Society of Nigeria. Prah, Kwesi Kwaa (ed.) (2002) Rehabilitating African Languages. Cape Town: CASAS MacBride, S.(ed) (1980) Many Voices, One World Paris: Unesco Press Oyelaran, O.O. (1990) “Language, Marginalization and National Development in Nigeria”. In Emenanjo, E.E. (ed) Webb, Vic and Kembo Sure (Ed) (2000). African Voices: An Introduction to the Language and Linguistics of Africa Oxford University Press. 12 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde APPENDIXES APPENDIX ONE: AFRICA”S LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY 13 S.T. Babatunde Generally speaking, they are grouped into four language families. These are Afro-Asaiatic, Nilo- 14 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde we want to pay more attention to them, and discuss their spread from their place of origin. (ADAPTED FROM WEBB AND KEMBO-SURE, 2000:30-34) 15 S.T. Babatunde APPENDIX TWO APPENDIX THREE : TWO SAMPLES FROM NIGERIA Tentatively, we have discovered that Plateau State, with a land area of 58030 square kilometres and a population of roughly 3 million1 has the following 62 languages represented in it: Berom, Hausa, Charawa, Pyen, Gashit, Atem, Geomai, Kwala, Youn, Shendam, Amper, Piapuna, Koi, Ankwai, Gade, Fulani, Gbagyi, Yeskwa, Mada, Goro, Afo, Gwandara, Tarok, Lengtang, Alago, Ake, Tiv, Kanuri, Mighili, Angas, Tal, Fier, Kantana, Miango, Rundre, Rom, Irrigwe, Rukuba, Gwari, Buji, Mangu, MgaMwaghavul, Romkulere, Aguta, Eloyi, Gade, Ebira, Bassa, Bogghom, Bashawara, Dengi, Mada, Tarok, Jukun, Eggon, Rindiri, Arum, Moma, Montol, I?oma, Ba'ap, Pidgin. And even more complex and intriguing situation is that of Cross River State, with a land area of about 30000 square kilometres and a population of roughly 3 million (Essien 1982:117). It has tentatively, the following 67 indigenous languages: ANNANG, EFFIK, IBIBIO, EJAGHAM, BOKYI, BEKWARA, Biase, Quasi, Ugep, Bembe, Yakkur, Eket, Sankula, Obudu, Oron, Ochukwayan, Yala, Ishibori, Ekajuk, Etung, Ukele (with the northern dialect being unintelligible to the southern dialect), Yahe, Wori, Ibeno, Nkari, Qua, Ofutop, Nkim, Nde, Nselle, Nta (Atam), Mbube, Bette, lyala (Yala), Utukwana, Tiv, Yache, Agoi, Mbembe, Loka, Abini, Ehom, Doko, Lekobi, Agwagwune (with the Abini and Idim dialects), Ikom-Olulumi, Akama, lyoniyong (threatened with extinction since the young people speak Effik as their L, - [Essien 1982:120]), Kohumono, Korop, Kukule, Kukule (Ukele), Legbo (Agbo), Leyigha, Lenyima, Luko, Lekoli, Lubila, Mbembe, Ubaghara, Ukpet-Ehom, Umon, Yala, Yache, Nnam, Abanyom, Igede. (ADAPTED FROM ADEGBIJA ,1994a :143) 16 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde 17 S.T. Babatunde 18 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde 19 S.T. Babatunde 20 Socio-cultural Effects of Language by S.T. Babatunde 21