SOL Connections

advertisement

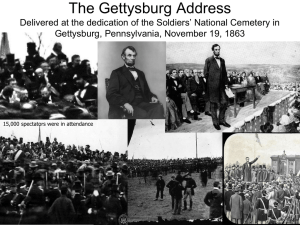

Does the Camera Ever Lie? Analyzing Civil War Images SOL Connections: VS.7b The student will demonstrate knowledge of the issues that divided our nation and led to the Civil War by describing Virginia’s role in the war, including identifying major battles that took place in Virginia. ACTIVITY (complete this activity) 1. Choose a photograph from inside the folder. 2. Look closely at the photograph. 3. Complete the photograph analysis guide. Gettysburg, Pa. Bodies of Federal soldiers O'Sullivan, Timothy H., 1840-1882, photographer. 1863 July. 4. Read more about how this photograph was made. What new ideas about the photograph do you have now? Add these thoughts to your photograph analysis guide. REFLECTION (consider these questions) 5. How would you introduce the above activity to your students? What would you have them do after completing the guide and the reading? 6. What do you think makes this lesson engaging for students? What drawbacks do you see to this lesson? 7. What would be an appropriate “learning goal” for this activity? James River, Va. Sailors on deck of U.S.S. Monitor Gibson, James F., b. 1828, photographer 1862 July 9. Where can I find these images and stories? From www.loc.gov, click on American Memory Click on War, Military. Several Civil War Collections will come up. Choose Civil War ~ Brady Studio and Others ~ Photographs ~ 1861-1865 Scroll down until you see “Special Presentations.” Click on “Does the Camera Ever Lie?” Fort Wagner, Folly Island, South Carolina] [Stereograph] ca.1861-ca.1865 http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/cwnyhs:@field(DOCID+@lit(ad24002)) Where can I find other Civil War images? From www.loc.gov, click on American Memory Click on War, Military. Several Civil War Collections will come up. 1) Choose one of the collections and search within that collection by using Search by Keyword or Browse by Subject OR 2) Type a search term in the box in the center that says “Search collections containing” (NOT in the upper-left hand corner) Remember to choose “gallery view” to see thumbnails of the items. Also, remember to use search terms that reflect the language of the time. PHOTOGRAPH ANALYSIS SHEET Objective Observations Subjective Observations Describe what you see in the photograph-the forms and structures, the arrangement of the various elements. Avoid personal feelings or interpretations. Your description should help someone who has not seen the image to visualize it. Describe your personal feelings, associations and judgments about the photograph. Always anchor your subjective response in something that is seen. For example, "I see...., and it makes me think of ....." Questions you have about the object: Gettysburg, Pa., Dead Confederate soldiers in "the devil's den" Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July 1863 Detail from Gettysburg, Pa. Dead Confederate soldier in the devil's den. Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-7942) Like other Civil War photographers, Alexander Gardner sometimes tried to communicate both pathos and patriotism with his photographs, reminding his audience of the tragedy of war without forgetting the superiority of his side's cause. Sometimes, the most effective means of elevating one's cause while demeaning the other was to create a scene -- by posing bodies -- and then draft a dramatic narrative to accompany the picture. Compare the photographer's 1865 narratives with a contemporary analysis: A Sharpshooter's Last Sleep. By Alexander Gardner Text for Plate 40 in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, published, 1865-66. A burial party, searching for dead on the borders of the Gettysburg battle-field, found, in a secluded spot, a sharpshooter lying as he fell when struck by the bullet. His cap and gun were evidently thrown behind him by the violence of the shock, and the blanket, partly shown, indicates that he had selected this as a permanent position from which to annoy the enemy. How many skeletons of such men are bleaching to-day in out of the way places no one can tell. Now and then the visitor to a battle-field finds the bones of some man shot as this one was, but there are hundreds that will never be known of, and will moulder into nothingness among the rocks. There were several regiments of Sharpshooters employed on both sides during the war, and many distinguished officers lost their lives at the hands of the riflemen. The first regiment was composed of men selected from each of the Loyal States, who brought their own rifles, and could snuff a candle at a hundred yards. Some of the regiments tried almost every variety of arms, but generally found the Western rifle most effective. The men were seldom used in line, but were taken to the front and allowed to choose their own positions. Some climbed into bushy trees, and lashed themselves to the branches to avoid falling if wounded. Others secreted themselves behind logs and rocks, and not a few dug little pits, into which they crept, lying close to the ground and rendering it almost impossible for an enemy to hit thim. Occasionally a Federal and Confederate Sharpshooter would be brought face to face, when each would resort to every artifice to kill the other. Hats would be elevated upon sticks, and powder Copied from glass, wet collodion negative, flashed on a piece of paper, to draw the opponent's fire, not always with success, however, and alternate exposure, substantially identical to sometimes many hours would elapse before either party could get a favorable shot. When the the one from which Gardner made Plate 40. Full Image | Bibliographic Record armies were entrenched, as at Vicksburg and Richmond, the sharpshooters frequently secreted LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa., Dead themselves so as to defy discovery, and picked off officers without the Confederate riflemen being Confederate soldiers in "the devil's den" Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July able to return the fire. The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter. 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-0277) By Alexander Gardner Text for Plate 41 in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, published, 1865-66. Copied from glass, wet collodion negative from which Gardner made Plate 41. LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa., Dead Confederate soldier in the devil's den. Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-7942) On the Fourth of July, 1863, Lee's shattered army withdrew from Gettysburg, and started on its retreat from Pennsylvania to the Potomac. From Culp's Hill, on our right, to the forests that stretched away from Round Top, on the left, the fields were thickly strewn with Confederate dead and wounded, dismounted guns, wrecked caissons, and the debris of a broken army. The artist, in passing over the scene of the previous days' engagements, found in a lonely place the covert of a rebel sharpshooter, and photographed the scene presented here. The Confederate soldier had built up between two huge rocks, a stone wall, from the crevices of which he had directed his shots, and, in comparative security, picked off our officers. The side of the rock on the left shows, by the little white spots, how our sharpshooters and infantry had endeavored to dislodge him. The trees in the vicinity were splintered, and their branches cut off, while the front of the wall looked as if just recovering from an attack of geological small-pox. The sharpshooter had evidently been wounded in the head by a fragment of shell which had exploded over him, and had laid down upon his blanket to await death. There was no means of judging how long he had lived after receiving his wound, but the disordered clothing shows that his sufferings must have been intense. Was he delirious with agony, or did death come slowly to his relief, while memories of home grew dearer as the field of carnage faded before him? What visions, of loved ones far away, may have hovered above his stony pillow! What familiar voices may he not have heard, like whispers beneath the roar of battle, as his eyes grew heavy in their long, last sleep! On the nineteenth of November, the artist attended the consecration of the Gettysburg Cemetery, and again visited the "Sharpshooter's Home." The musket, rusted by many storms, still leaned against the rock, and the skeleton of the soldier lay undisturbed within the mouldering uniform, as did the cold form of the dead four months before. None of those who went up and down the fields to bury the fallen, had found him. "Missing," was all that could have been known of him at home, and some mother may yet be patiently watching for the return of her boy, whose bones lie bleaching, unrecognized and alone, between the rocks at Gettysburg. The Analysis. This analysis is based upon the pioneering work of the historian William Frassanito in his book Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1975, pp. 186-192). Alternate Exposure for Plate 40. A Sharpshooter's Last Sleep. Full Image | Caption Plate 41. The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter. Full Image | Caption Frassanito studied six photographs of this dead soldier made by the photographers Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan at the Gettysburg battlefield in July 1863. Geographic features place four of the six photographs at the southern slope of Devil's Den (top) and two at what Gardner called the "sharpshooter's den" (bottom). Frassanito argues that the original location of the body was the southern slope of Devil's Den, suggesting that the soldier was probably an infantryman, killed while advancing up the hillside. After taking pictures of the dead soldier from several angles, the two photographers noticed the picturesque sharpshooter's den -- forty yards away -- and moved the corpse to this rocky niche and photographed him again. A blanket, visible under the soldier in another version of the sharpshooter's den image (not shown here), may have been used to carry the body. The type of weapon seen in these photographs was not used by sharpshooters. This particular firearm is seen in a number of Gardner's scenes at Gettysburg and probably was the photographer's prop. The amount of time expended photographing this one body indicates that this may have been one of the last bodies to be buried and Gardner may have felt that he was running out of subjects. In his text in the Sketch Book, Gardner recalls seeing the body again about four months after the battle, when the Gettysburg cemetery was dedicated in November 1863. Frassanito points out that the body would not have been left unburied that long, nor would the rifle have survived the hordes of relic hunters who swarmed over battlefields. But Gardner's story succeeded in transforming this soldier into a particular character in the drama, a man who suffered a painful, lonely, unrecognized death. 3. Copied from glass, wet collodion negative, alternate exposure, substantially identical to the one from which Gardner made Plate 40. (Differences between exposures include: the location of the small objects near the body, the age markings on the negatives, and the distance of the camera lens from the body.) LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa., Dead Confederate soldiers in "the devil's den" Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-0277) [Return to Top] 4. Copied from glass, wet collodion negative from which Gardner made Plate 41. LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa., Dead Confederate soldier in the devil's den Photographed by Alexander Gardner, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-7942) [Return to Top] Gettysburg, Pa. Bodies of Federal soldiers, killed on July 1, near the McPherson woods]. O'Sullivan, Timothy H., 1840-1882, photographer. CREATED/PUBLISHED 1863 July. Detail from Incidents of the war. A harvest of death, Gettysburg, July, 1863. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, July 1865 (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8184-7964A) The eye of the camera does not pass judgment on its subjects. Yet Civil War photographers could stir patriotism with their photographs, praising their compatriots while pitying their foes. Photographer Alexander Gardner wrote poignant narratives to accompany his photographs, occasionally inventing stories to make his point. In his Sketch Book, Gardner used two photographs of these dead soldiers, identifying them first as Confederate and then as Union. Compare the photographer's 1865 narratives with a contemporary analysis: A Harvest of Death. By Alexander Gardner Text for Plate 36 in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, published, 1865-66. Slowly, over the misty fields of Gettysburg -- as all reluctant to expose their ghastly horrors to the light -- came the sunless morn, after the retreat by Lee's broken army. Through the shadowy vapors, it was, indeed, a "harvest of death" that was presented; hundreds and thousands of torn Union and rebel soldiers -- although many of the former were already interred -- strewed the now quiet fighting ground, soaked by the rain, which for two days had drenched the country with its fitful showers. A battle has been often the subject of elaborate description; but it can be described in one simple word, devilish! and the distorted dead recall the ancient legends of men torn in pieces by the savage wantonness of fiends. Swept down without preparation, the shattered bodies fall in all conceivable positions. The rebels represented in the photograph are without shoes. These were always removed from the feet of the dead on account of the pressing need of the survivors. The pockets turned inside out also show that appropriation did not cease with the coverings of the feet. Around is scattered the litter of the battle-field, accoutrements, ammunition, rags, cups and canteens, crackers, haversacks, &c., and letters that may tell the name of the owner, although the majority will surely be buried unknown by strangers, and in a strange land. Killed in the frantic efforts to break the steady lines of an army of patriots, whose heroism only excelled theirs in motive, they paid with life the price of their treason, and when the wicked strife was finished, found nameless graves, far from home and kindred. Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation. Field where General Reynolds Fell. Battle-Field of Gettysburg. Copied from Gardner's Plate 36. LC Caption: Incidents of the war. A harvest of death, Gettysburg, July, 1863. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LCB8184-7964-A) By Alexander Gardner Text for Plate 37 in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, published, 1865-66. Copied from glass, wet collodion negative from which Gardner made Plate 37. LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa. Bodies of Federal soldiers, killed on July 1, near the McPherson woods. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LCB8171-0234) About nine o'clock on the morning of the 1st of July, 1863, the Federal cavalry, under General Buford, met the Confederates two miles beyond Gettysburg, on the road to Chambersburg. The rebel infantry was preceded by a small body of their cavalry, which dispersed the militia wherever met with, and which, charging into our cavalry, was captured, not a man escaping. The Confederates immediately threw a division of infantry into line, and advanced upon our cavalry, which dismounted, and by slowly falling back from one stone wall to another, impeded the progress of the enemy very materially. The cavalry had just taken up the last available line of defence beyond Gettysburg, when, eleven o'clock, General Reynolds arrived with the 1st corps on a double-quick. The enemy then halted for a short time, re-formed their lines, and prepared to charge, which was met by a severe fire from the advance of our infantry, which went into line as rapidly as the regiments could be brought up. General Reynolds, appreciating the importance of holding the Seminary Ridge, rode out into the field, and directed the posting of the troops, and while engaged in this work, received a shot in the neck, falling lifeless to the earth. His remains were brought off the field under a withering fire, which lasted until night, our troops, overwhelmed by numbers, slowly falling back, and finally taking a position on Cemetery Ridge, which was next day occupied by the rest of our army, and became the battle-ground of the succeeding days. The dead shown in the photograph were our own men. The picture represents only a single spot on the long line of killed, which after the fight extended across the fields. Some of the dead presented an aspect which showed that they had suffered severely just previous to dissolution, but these were few in number compared with those who wore a calm and resigned expression, as though they had passed away in the act of prayer. Others had a smile on their faces, and looked as if they were in the act of speaking. Some lay stretched on their backs, as if friendly hands had prepared them for burial. Some were still resting on one knee, their hands grasping their muskets. In some instances the cartridge remained between the teeth, or the musket was held in one hand, and the other was uplifted as though to ward a blow, or appealing to heaven. The faces of all were pale, as though cut in marble, and as the wind swept across the battle-field it waved the hair, and gave the bodies such an appearance of life that a spectator could hardly help thinking they were about to rise to continue the fight. The Analysis. This analysis is based upon the pioneering work of the historian William Frassanito in his book Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1975, pp. 222-229). Plate 36. Incidents of the War. A Harvest of Death. Full Image | Caption Plate 37. Field where General Reynolds Fell. Battle-Field of Gettysburg. Full Image | Caption In the text accompanying the first photograph -- Plate 36, titled Incidents of the War. A Harvest of Death. -Alexander Gardner describes the soldiers as dishonored Confederate troops who paid for their treason with their lives, dying a lonely battlefield death, buried by strangers in graves far from home. Close examination indicates, however, that the men in Plate 36 are the same soldiers seen in the second photograph -- Plate 37, titled Field where General Reynolds Fell. Battle-Field of Gettysburg. -- for which Gardner wrote a melancholy description of Union troops, calm and peaceful in death, so tranquil that they seem about to wake and rise. Several clues indicate that the images are two views of the same scene taken from opposite sides. One of the most obvious clues is a piece of rumpled clothing that shows the diamond badge worn only by Union 3d Corps soldiers. The numbers identify the individual bodies; to confirm these identifications, researchers may wish to compare the placement of hands and feet. Other features of the men's uniforms permitted Frassanito to identify them as Union. Topographic clues convinced him that the photographs were made in open fields near the Rose farm and close to the Emmitsburg Road. Under General Dan Sickles, the Union 3d Corps suffered heavy losses around Emmitsburg Road. General John Reynolds, commander of the 1st Corps and mentioned in Gardner's title, fell at a different location. 1. Copied from Gardner's Plate 36. LC Caption: Incidents of the war. A harvest of death, Gettysburg, July, 1863. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8184-7964-A) [Return to Top] 2. Copied from the Glass, wet collodion negative from which Gardner made Plate 37. LC Caption: Gettysburg, Pa. Bodies of Federal soldiers, killed on July 1, near the McPherson woods. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, July 1863. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction number: LC-B8171-0234) [Return to Top]