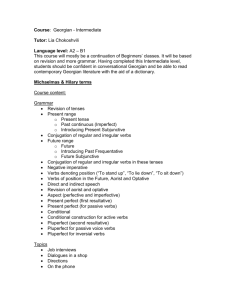

Fulbright-Hays Outline

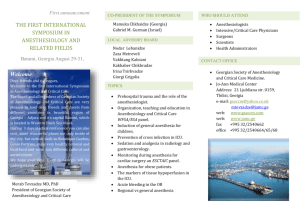

advertisement

William Eastwood 1 Georgian Baptists in the Republic of Georgia In the Republic of Georgia religion is the site of a national politics of authenticity. For centuries Orthodox Christianity has been a defining marker of “true” Georgianness. Resulting from historical and political processes, this element of authenticity underpins what I term a national dissonance in contemporary Georgian society. This dissonance exists between Georgians who follow the Orthodox Christian tradition and Georgians following other Christian traditions, like Protestantism, Pentecostalism, and Catholicism, all within a single socio-cultural context. In fact, Catholics and various Protestant groups have had a native presence in Georgia long before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In other words, the presence of many nonOrthodox Christian groups in Georgia is not the result of recent, Western missionary endeavors (Ramet 1998). My dissertation fieldwork as a Ph.D. candidate in Social-Cultural Anthropology at Indiana University will focus on Georgian Protestant Christians, specifically Georgian Baptists, who have had an extended presence on the ground but with little or no historical voice to show for it. Research Objectives My dissertation research will produce an in-depth ethnography of a religious community within an emerging nation-state. In doing so, it will broaden our understanding of religion as a place of contestation between the combined force of institutional power and public discourse and those citizens delegated to the social edge. The fieldwork for this ethnography will take place among members of the Evangelical Baptist Church of Georgia, specifically those who attend services at the main cathedral in Tbilisi, the capital city. This location will provide me a unique perspective into the local effects of government efforts to nation-build, including policy formation and implementation, constitution-making, and institution-building currently taking William Eastwood 2 place in Georgia. My investigation into the Baptist community, in particular, will connect to and shed light on the impact of nation-state building on the lives of those Georgians not in the Orthodox Christian majority. For my dissertation fieldwork I will address this national dissonance in Georgia by answering two questions: How are Georgian Baptists negotiating society’s dominant discourses and government power as they pursue their own religious choice? And, secondly, how do they practice their religion within that negotiated space? Methodology My approach to this research combines archival and ethnographic methods, including 1) archival research, 2) conducting interviews, 3) recording life histories, and 4) participantobservation. For archival research, I will use the church’s records to collect data on marriage, congregant demographics, and church history in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. Marriage records will primarily help to grasp family mores of congregants, specifically, how frequently have Baptists married outside their religious community to those of other religious traditions or to the non-religious. It is unclear how insulated the Baptist community has been from other Georgians. Marriage data will help determine an answer. Other types of demographic information will draw a clearer picture of the social make-up of members, such as age, economic class, employment status, and family background. Although the experience of Russian Orthodox believers in the Soviet era has garnered a small amount of attention (e.g. Davis 1995), along with recent work on Russian Baptists (Coleman 2005) and the Georgian Orthodox Church (Vardosanidze 2001), the experience of Protestants in Georgia in the last century is completely undocumented. Specific data about the Baptist community will contribute to our understanding of these believers’ experiences in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods, while comparing and William Eastwood 3 contrasting their experiences with what we know already about their Orthodox and Baptist counterparts. Interviews, both formal and informal, with leaders in the Baptist community will include pastors, deacons, and actively involved laypersons. These sessions will yield their perspectives and opinions about their community and about the Georgian nation and their place in it. Interviews will also afford me the opportunity to collect life histories from various members of the community, including the elderly, young adults, life-long Baptists, and those newly attending. These subjective narratives of individual experiences will provide a better sense of who Georgian Baptists are, what they believe, what attracts them to the Baptist tradition, how they relate to Orthodox Christianity, and their own personal journeys up to this point. I plan to record at least forty life histories. Conducting participant-observation in church services, meetings, and activities will provide me a vantage point from which to make observations and gather informal data within the community. I will see first-hand the public practice of their beliefs, allowing me to better understand who Georgian Baptists are by what they do in public gatherings, what their sermons are about, how they differ from their Orthodox neighbors, and how they differ from Baptists and other Protestants in the West. For example, the winter holidays of Orthodox Christmas, Orthodox New Year and the Orthodox observance of Great Lent are very important to Georgian Baptists as well. But how do Baptist commemorations and rituals differ from those of their Orthodox counterparts? Activities such as sermons, rituals performed from week to week, holiday celebrations, music, ecumenical activities, and efforts for social justice will be studied with an eye to see how Baptists differentiate themselves from the Orthodox majority and make meaningful lives as a religious minority. William Eastwood 4 Theoretical Approach National identity and Orthodox Christian identity share the same space in the dominant discourse of what it means to be an authentic Georgian. Indeed, legislation in recent years has attempted to protect and privilege this fused identity in the constitution. The politics surrounding this contemporary identity, how it emerged, and how non-Orthodox Georgians are living in light of it are complex processes, which up to this point have gone un-researched in the West. My study is informed by and will contribute to the following three theoretical projects: ethnic identity and nationalism, the anthropology of religion, and post-Soviet anthropology. According to Royce, following Barth, ethnic boundaries work in two directions: outwardly, demarcating one group from other groups, and inwardly, maintaining and managing shared differences and values (Barth 1969, Royce 1982). Whereas symbolic forms like dress, songs, poems, and food constitute outward boundaries, inner boundaries are maintained through the regulated “performance” of shared values. Chatterjee has demonstrated how in Indian cultural nationalism, these common values could fuel anti-colonial movements, because they were elements of a unique “cultural domain,” which outside forces could not subjugate or occupy (Chatterjee 1993). This domain was a central resource both in resisting colonial oppression and in making claims to national autonomy. Two things flowing from this discussion, then, directly inform my own study. First, Georgian Orthodox Christianity is a major component in Georgia’s “domain of values” and, second, contemporary Georgian national identity is directly related to the colonial machinations of the Russian empire and of the Soviet Union. Religion is so important today because it represents Georgia’s unique forms and values, which were used to mobilize Georgians toward national independence. It is under these circumstances that modern national identity and religious identity became intertwined. William Eastwood 5 Beyond an investigation into national identity, my work will show that religion itself is a source of powerful meaning and of validation for individuals and their life choices. Religion is much more complex than simply a space where various contests occur. My research will not only place religion within the realm of politics, but also place politics within the realm of religion, so to speak, by shedding light on how members of a particular religious minority are making their lives meaningful despite their political disadvantages. Similar studies have been taken up by Kipp (1995) and Poethig (2001). My own ethnographic account will join recent post-socialist ethnographies that are accounting for new identities emerging in the years after the fall of Soviet socialism (e.g. Goluboff 2003, Berdahl 1997, Petryna 2002). My research is ideally suited to take the study of post-socialist space one step further by addressing the challenge once posed by Katherine Verdery, namely, that post-socialism represents for the Western Academy a “conceptual vacuum” (Verdery 1996:38). Western studies of the Soviet Union were based on a dichotomy of Western Democracy versus Soviet Socialism, but once socialist regimes dissolved, this dichotomy that underlay the work of the Western Academy no longer held true. In other words, after the Cold War, how should we speak of formerly Soviet peoples, and, likewise, how should we speak of ourselves in the “West?” Western researchers are having to make sense of postSoviet realities that do not line up with the old black-and-white dichotomy that had underpinned earlier works. Rethmann poses the possibility that post-socialist anthropology might be ideally suited to offer new conceptualizations of this space, no longer basing theory on those "idiosyncratic descriptions" of particular places and/or peoples (Rethmann 1997:773). Collaboration, then, will characterize how I conduct research in Georgia. By collaboration, I mean a concerted and deliberate partnership between a Western researcher and William Eastwood 6 his informants that bridges our ideological differences that continue to exist after the Cold War. In their recent work, Fieldwork Dilemmas, De Soto and Dudwick bring to the fore discussions about these Cold War-era ideological barriers that continue to separate Western anthropologists and their informants. If there is a consensus among the articles in that collection it is that collaboration is the first and most important step in tearing down those barriers. Research agendas will be successful because trust and understanding will expose and replace out-moded and self-defeating assumptions about former foes. Attention to research equity will mean that projects and research topics benefit interests on both sides of the table. In other words, Western scholars enter the field treating informants as co-contributors, who are also actively participating in the formulation of knowledge. I enter this dissertation project, then, with the assumption that I am not just a researcher; I am also entering into trust relationships with other, fellow interested persons. The members of the Georgian Baptist community will be very much my colleagues and, in part, co-authors to this ethnographic project. Their input is the cornerstone of my investigation. Their community, because it is the focus of this project, is a priority for all of us. In accordance with ethical norms as laid out by Indiana University’s Human Subjects Research Board, I will submit to each collaborator transcriptions of his or her own interviews and/or life histories for review, correction, and final consent. I will also present copies of the final dissertation and any subsequent publications to these congregations for their use, while maintaining the anonymity of those with whom I worked. Preliminary Research These research objectives, methods, and theory are based on two years of doctoral course work, a Master’s degree in Russian and East European Studies in 2003 from Indiana University, William Eastwood 7 and nine months abroad on a Fulbright IIE fellowship. Coursework that is especially helpful to my understanding of Georgia in post-Soviet space has been the course “The Anthropology of Russia and Eastern Europe.” Based on class discussions, readings, and my prior overseas experience, my term paper for this course offered an interpretation of my own personal experiences with Georgian hospitality. I discussed how important this characteristic is for Georgians in differentiating themselves from their “guests” (i.e. foreigners in their country). In addition, courses in “Nationalism and Cultural Identity,” “Ethnic Identity,” and “Culture and Law” are helping me to analyze the political processes from which ethnic identities emerge and how governments attempt to preserve and protect ethnic characteristics. Two seminars, one on the history of the Soviet Union, where I compiled a literary review of Western sources on religion in the Soviet Union, and the other on democratization in the Newly Independent States, have helped to form my understanding of Georgia’s Soviet past and its efforts to overcome the shortcomings of that legacy. My Master’s degree in Russian and East European Studies from Indiana University culminated in the thesis, “When Discourses Clash: Religious Violence in Georgia.” In it, I argued that the religious violence that took place in Georgia in the late 1990s could be explained in terms of competing discourses: a dominant discourse of authentic Georgianness that is characterized by Orthodox Christianity versus new discourses, emphasizing citizenship instead of religious affiliation. Expanding on Mary Douglas’ classic work on social taboo, non-Orthodox Christians, which include, among others, Catholics, Baptists, Pentecostals, and the outlying Jehovah’s Witnesses, occupy a discursively undefined “no-man’s-land,” a non-category, or at least a very cloudy one (Douglas 1966). Extremists and ideologues found it easy to scapegoat them given the deplorable economic climate and ineffectual political leadership in the late 1990s. William Eastwood 8 In the eyes of devout Georgian Orthodox and national patriots alike, these particular religious minorities, by nature of their liminal position, were suspected of threatening the well-being of the nation and the political-religious power of the Georgian Orthodox Church. My thesis research led to the opportunity to go to Georgia in 2003-2004 as a Fulbright IIE student fellow. I spent nine months in Georgia investigating the Georgian Orthodox Church’s role in democratization. I learned from interviews and following the activities of the Church in the media that the Church does not often have to lobby for its interests in state affairs, because it already enjoys a monopoly of the public’s favor. It has risen to this powerful position in society, because it has become a living symbol of the nation’s centuries-long survival despite countless invasions, occupations, and foreign oppression. This symbolic power is so pervasive that both the religious and non-religious gather around the institution and come to its aid. While in Tbilisi I was able to attend services at the main cathedral of the Evangelical Baptist Church. There I saw first-hand how these congregation members were bustling with activity. They regularly engaged in matters of social justice, ecumenicism, feeding the hungry, and equipping themselves through education. From my perspective, these Baptists were neither foreigners nor anti-Orthodox, nor were they the threat that extremists and nationalist ideologues have made them out to be in the mass media. Indeed, this disconnect that I witnessed between how Georgian Baptists are portrayed in popular discourse and how they conduct themselves in reality characterizes my current dissertation research questions. Academic Preparations My Fulbright experience allowed me to form two worthwhile acquaintances. The first was with the head of the Georgian Baptist community, Bishop Malkhaz Songulashvili. This native Georgian and Oxford graduate was supportive of my research goals while I was there, and William Eastwood 9 since then, we have remained in contact with each other. He remains interested and committed to my current research as detailed in his letter of support enclosed in this application. The second acquaintance was with Dr. Rusiko Amirejibi, professor of Linguistics at Tbilisi State University and director of the International Center for Georgian Language (ICGL). This center provided me with top-quality Georgian language courses. Dr. Amirejibi’s enthusiasm about my current project and confidence in my abilities to carry the project out are clear in the language evaluation form that she has agreed to fill out on my behalf. My extensive Georgian language training has prepared me for dissertation research abroad. My initial formal study of Georgian began at Indiana University’s eight-week summer workshop in 2001. During the rest of my Master’s coursework, I had a bi-weekly, one-on-one language lesson with Dr. Dodona Kiziria, a native Georgian and professor in the Slavics department at Indiana University. My proficiency grew exponentially upon living in Georgia for nine months as a Fulbright student fellow. On top of my research endeavors, I participated in intensive, one-on-one daily lessons with a native Georgian instructor. These sessions averaged four hours a day, five days a week, for a total of about eight months. I will continue advanced language courses through the ICGL when I return, because advanced Georgian language training is unavailable anywhere outside Georgia. I intend to return to Georgia in the summer of 2006 on a pre-dissertation trip to finalize my fieldwork abroad. This trip will give me the opportunity to make living arrangements and contact the United States embassy. This summer trip will also allow me to meet with Baptist leaders to reestablish contact with them and initiate the first steps of my fieldwork. William Eastwood 10 Plans to Share & Guidance My academic advisor, Dr. Beverly Stoeltje, and other dissertation committee members, who specialize in nationalism, ritual, and post-Soviet space, will review my research. I will be in regular communication with them during the course of my fieldwork. The committee, Professor Stoeltje in particular, will provide the input and mentorship necessary to help me decide the best strategies for interpreting data and completing the final dissertation. My findings will be shared in scholarly articles, presentations at conferences, and participation in seminars. The data compiled from this fieldwork and the preliminary conclusions I reach are significant to understanding contemporary politics and identities in Georgia. They are also important for raising awareness about the lives of disenfranchised religious minorities. Therefore, I will make every effort to share my findings and conclusions in an appropriate manner with Georgian social scientists, scholars, and government leaders. In closing, I propose to begin my grant in January 2007. I will focus my initial energies into becoming involved in the Baptist community and participating in the religious holidays that were mentioned earlier (e.g. Orthodox Christmas, Orthodox New Year, Lent, Easter). The first half of the trip will divided up between investigating church records, making appointments for official interviews with church officials and important laypersons, and observing religious holiday celebrations. The second half of the trip will be more focused on recording life histories and transcribing them into written form for consultants’ approval. After returning to the United States, I will begin writing the dissertation and work toward its completion in 2008. Afterward, I will seek work in an academic setting, teaching students and training new anthropologists in the methods and theories of socio-cultural anthropology and in the ethnographic richness and cultural importance of the Republic of Georgia.