State and District Influences on - WCER

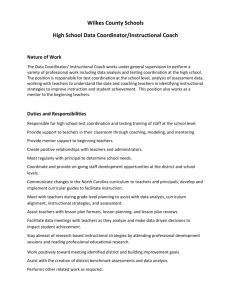

advertisement