Content creation process

advertisement

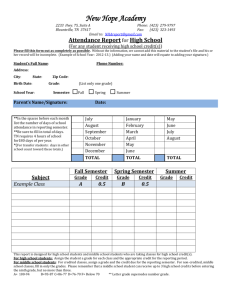

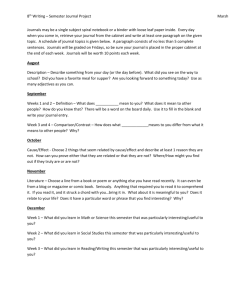

E-LEARNING IN THE FIRST SEMESTER OF AN UNDERGRADUATE MEDICAL CURRICULUM Josef Smolle, Institute of Medical Informatics, Reinhard Staber, Virtual Medical Campus Department, Florian Hye, Virtual Medical Campus Department, Elke Jamer, Student RecordsRegistrar’s Office, Silvia Macher, Quality Assurance and Organization of Teaching, Heide Neges, Quality Assurance and Organization of Teaching, Gilbert Reibnegger, Vice-Rector’s Office for Teaching and Studies, Medical University of Graz, Austria Context of the virtual learning environment at the Medical University of Graz In 2002, an integrated curriculum of human medicine was started at the Medical University of Graz, Austria. The curriculum was aimed at an early integration of basic sciences with clinical application, a problem-centred design and collaborative teaching of various disciplines [1-3]. The curriculum is organized in modules of five weeks each, with various specialties contributing to each module. In addition, tracks referring to biomedical background, medical skills, and communication/ supervision/ reflexion extend through the whole curriculum. In the 6th year, a practical undergraduate internship and 4 weeks of general practice are implemented. The integrated approach of the curriculum requires learning material beyond that of conventional textbooks, since standard textbooks do not fulfil the requirements of interdisciplinary teaching and learning. Therefore, a virtual learning environment was implemented with the start of the curriculum, which is designated as Virtual Medical Campus (VMC) Graz [4]. The VMC Graz was initially supported as a project by the Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture in 2002, and as a strategic development in 2005. From the beginning, the VMC was designed to provide an overview of the structure of the entire curriculum, which was gradually filled with learning objects referring to the needs of the various lectures, seminars and practical courses. At first, the VMC was only used to provide material in addition to face-to-face education. Meanwhile, an increasing number of lectures is available in electronic form instead of face-to-face teaching, providing blended learning in selected topics. In addition, besides human medicine, the curricula of dental medicine and of nursing science have been implemented in the VMC, and cooperative programs have been started with the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, and the Medical Faculty of Maribor, Slovenia. At the Medical University of Graz, usually an average of 800 students starts their curriculum in human medicine every year. According to Austrian federal law, up to 2004 each Austrian student applying for human medicine was admitted. In June 2005, the legal situation changed since the European Union considered it incompatible with European Union regulations that Austrian universities accepted all Austrian students, while requiring proof of a university place in their home country for students of other European countries. Therefore, from beginning of the academic year 2005/06 onwards, all European students applying for a university place in Austria had to be treated equally as the Austrian applicants. This is particularly important for human medicine, since about 25.000 applicants are rejected in Germany every year, and each of them has now gained the right to apply at an Austrian Medical University. In the first run in 2005, more than 3000 students applied for human medicine at the Medical University of Graz, about 2000 of them coming from Germany. Therefore it became evident that the Medical University would not be able to accomplish traditional face-to-face teaching for such a large number of students. On the other hand, a selection process had already been designed for the end of the first semester. Therefore the Medical University rector and the vice-rector for teaching and studies decided to accept all applicants at the beginning of the semester, and to perform a selection examination at the end of the semester. In order to manage the large number of students, teaching in the first semester was entirely based on the virtual e-learning environment already available. At the Medical University of Graz, a total of 300 university places are available from the second stage onwards every year. Since 200 places were already occupied by students who had finished the first stage during the last year, only 100 new places were available. Content creation process Structure of the first semester of the medical curriculum The first semester of the medical curriculum of human medicine includes three modules and one track course. The majority of the courses was designed as lectures, only a minority was intended in an interactive workshop format. The contents of the first semester comprise mainly basic sciences (physiological chemistry, biophysics), anatomical nomenclature and general biology. In addition, however, first insights into clinical disciplines are provided. In a regular first semester, a practical course in nursing is included. In the academic year 2005/06, however, this course had to be postponed until the second semester, since more than 1.000 students were beyond the capacity of our teaching hospital. The following list shows the formal structure of the first term: Module 01: From law of nature to life; 5.1 ECTS credit points - Basics of physiological chemistry I - Basics of biophysics I - Anatomical terms and definitions Module 02: Components of life; 4.7 ECTS credit points - Osteology - Basics of physiological chemistry II - Basics of biophysics II Module 03: Cell, tissue, health issues; 7.1 ECTS credit points - Chemical components of living organisms - The cell - Genetics - Tissues - Embryonic development - Preventive medicine Track: Introduction to medicine; 7.7 ECTS credit points - Practical course in nursing - Introductory clinical lectures - First aid - Physical examination Strategy for content creation Though several learning objects were already available from former years, the e-learning contents for pure online learning had to be reshaped, and a large number of learning objects had to be newly created. The vice-rector’s office for teaching and studies invited all academic staff involved in the first semester to five consecutive workshops, each of these workshops dealing with a certain aspect of the ongoing virtual semester. The workshops were dedicated to content requirements for virtual lectures, content requirements for virtual seminars, organization of the track “Introduction to medicine”, organization of the final examinations, and eventual impact of high school credits. The team of staff participating in the workshops agreed that each learning unit should refer to a particular textbook chapter when appropriate, and had to contain an electronic learning object of the computer-based training type, with a minimum of five frames for a lecture learning unit and a minimum of 20 frames for a seminar learning unit. Computer-based training learning objects of seminar learning units were considered to be obligatory for students. Additional presentation and visualization objects were encouraged. In learning units without a textbook reference, presentation and visualization objects covering the whole topic were mandatory. For practical aspects, interactive simulations and video clips were recommended. Furthermore, deadlines for the finalization of the electronic contents have been agreed upon. With October 1st, the beginning of the semester, all textbook references of the virtual semester had to be online, together with the first part of module 1. The other contents had to be finished gradually according to a fixed time table, with the last objects of the virtual semester to be finished by December 20th. Types of learning objects A total of 200 learning objects of the interactive computer-based training (CBT) type were created [5], each comprising between 5 and 48 frames. This type of learning object is based on the branching tutorial programs of Crowder, with elaborated feedback to each choice according to the concept of Musch [6]. Many frames were accompanied by images. The CBT learning objects have been generated by a simple-to-use authoring tool developed for the Virtual Medical Campus Graz. At the end of each learning path, students have the opportunity to transmit an automatically created message to the system indicating individual data of the student and the scoring achieved in the particular CBT learning object. Submission of this message was obligatory for CBT learning objects linked to seminar-type learning units. Presentation and visualization learning objects (150 learning objects) were mainly created using Powerpoint® or Acrobat PDF® format. In addition, several HTML-based presentation and visualization learning objects were created. Three interactive simulations were used in biophysics, and four video clips were created for the topics “first aid” and “physical examination”. Organization of the final examinations After one semester of distance learning through the Virtual Medical Campus, all students were invited to take part in the final examinations which were scheduled on two consecutive days in Graz in January. On the first day, three consecutive examinations referring to modules 1, 2, and 3, respectively, had to be performed. Each of these module examinations consisted of 60 multiple choice questions. Students obtained regular marks ranging from 1 (very good) to 5 (not passed) for each of the three module examinations. The limit for gaining a positive mark was a proportion of at least 66 % correct answers. On the second day, a summative test comprising all topics of the semester was performed with 420 multiple choice questions. For this test, no regular marks, but only scoring points according to the number of correctly answered questions were given. Finally, a ranking of all students was created, where the marks of the module examinations were weighted with 40 % and the points achieved in the summative test with 60 %. Student’s access, system performance and user interaction 3336 Students pre-registered for the virtual semester. From the beginning, it was communicated that the semester will take place by e-learning only, and that only 100 students will earn a university place for the second semester. 1269 students finally registered, with about 40 % of students from Austria, 45 % students from Germany and 15 % of students from other countries. Temporary log-in accounts were activated for all pre-registered students on October 1st, and were gradually replaced by full accounts as soon as an individual had fulfilled all formal steps of registration. During the semester, 858.000 visits to learning objects were recorded. Students used the electronic learning system 24 hours a day for all days of the week, with up to 17.000 visits per day. The highest data traffic was recorded between 12.00 and 18.00 o’clock, but usage continued with tapering intensity until the early morning, with the number of visits rising again by 6.00 o’clock. There were only 4 scheduled interruptions of online access for a couple of hours due to system upgrading. There were no unscheduled or unexpected interruptions and no significant delays in online acess. Students sent in a total of 257.000 feedbacks from CBT learning objects, most of the feedbacks indicating a score of 85 % correct answers and higher. Figure 1 shows the distribution of scores in the CBT feedbacks of a particular not obligatory CBT learning object referring to anatomical terminology. 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 85 90 95 100 Figure 1: Student’s feedback of learning object “Anatomia systemica I”, Anatomical terms and definitions, Module 1. In 822 feedbacks, students achieved 98.3 +- 3.1 % correct answers. Communication between students and teachers was managed through e-mail forms submitted by students. The forms were forwarded to the particular teacher concerned, and the answer of the teacher was published together with the original question as an appendix to each of the modules. By this approach, repeated identical questions had only to be answered once. During the semester, 724 answers were created by teachers filling a total of 113 printed pages in A4 PDF format. Examination results In each of the module examinations, all marks ranging from 1 to 5 were represented. 104 students had positive marks in all three examinations, 96 of them were within the 100 best ranked students after the summative test has additionally been taken into account. Remarkably, there was a close correlation between the marks obtained in the module examinations and the scores obtained in the summative test (r = 0.72; p < 0.00001) already within the subgroup of the 100 best students. This finding illustrates that both parts of the ranking system (module examinations and summative test) have a high reproducibility within the subgroup of high performing students. Positive marks were achieved in 17.1 %, 23.6 % and 14.5 % in the three module examinations, with 66 % correct answers being the pre-set threshold for a positive mark. A more detailed analysis of module 1 examination revealed striking differences in outcomes depending on the electronic learning objects provided. When the contents were completely represented by computer-based training learning objects, 65.9 +- 0.7 % correct answers were achieved, compared to only 51.4 +- 0.5 % when the contents were not fully represented by computerbased training learning objects (t-test for paired values: t = 28.3, p < 0.0001). 100 80 60 40 20 0 CBT(+) CBT(+/-) Figure 2: Multiple choice questions referring to topics which had been entirely represented by computer-based training learning objects (CBT(+)) were answered correctly in a significant higher proportion than questions referring to topics which had only partially been represented by computerbased training learning objects (CBT(+/-)). Lessons learned from the virtual semester Our experience shows that it is possible to teach a large cohort of students in the first semester of human medicine through e-learning only. It became evident that high-performing students were particularly able to face the challenge successfully. On the other hand, it seems to be not so easy for medium- or low-performing students to acquire the necessary knowledge and intellectual skills through pure e-learning. This might particularly be true when – as in our case – the very first semester is entirely virtualized, and might be less important when only a proportion of lectures in higher semesters will be based on e-learning in a blended learning approach. One has to take into account, however, that there were other changes beside the switch from face-toface teaching to e-learning. At first, the amount of knowledge presented and examined was higher than in previous years, since there were more lecture units and fewer reflective seminars and practical courses. Furthermore, it was for the first time that all module examinations had to be passed on the same day, since in previous years the module examinations could be passed gradually at 5 – 8 week intervals. Finally, the whole amount of MC questions had been newly prepared, so that regular training of questions used in prior examinations was only of minor help. Remarkably, examination results seem to depend on the method of electronic delivery of the contents. When computer-based training learning objects covered the contents of an entire topic, than the performance of all students at the examinations was considerably better than when there were only few computer-based training frames giving selected hints only and leaving the main part of knowledge transfer to textbook references or presentation and visualization learning objects. Complete e-learning in the first semester of human medicine was performed in a singular situation confounded by political and organisational constraints. It became evident that it can be successfully performed from a formal point of view, relying on a technically stable virtual learning environment and dedicated staff ready to undertake the challenges of virtualization. When the first semester is studied entirely in a remote learning format, a high degree of self competencies is needed by students to perform successfully. Results obtained in the subsequent examinations seem to be highly selective and reproducible particularly in the subgroup of high-performing students. In the future, special emphasis will have to be put on the mode of electronic delivery, the types of learning objects, degree of elaboration, guidance of the learning process according to individual needs, individual feedbacks and time consumption on the one hand, compared with examination results on the other. Thereby, the discussion on e-learning methods, drawbacks and merits will shift from formal and theoretical discussions towards collecting evidence from experimental and field data. This approach may finally result in a reliable concept of evidence-based e-learning. References 1 BAROFFIO A, GIACOBINO JP, VERMEULEN B, VU NV (1997) The new preclinical medical curriculum at the university of Geneva: Processes of selecting basic medical concepts and problems for the PBL learning units. In: Scherpbier AJJA, VanderVleuten CPM, Rethans JJ, VanderSteeg AFW, editors. Advances in medical education. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 498-500. 2 EGGER JW (2005) Biopsychosoziale Medizin als Leitbild für die aktuelle Diplom-Studienordnung Humanmedizin. Psychologische Medizin 16:50-55. 3 GLASGOW NA (1997) New curriculum for new times. A guide to student-centered, problem-based learning. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. 4 SMOLLE J, STABER R, JAMER E, REIBNEGGER G (2005) Aufbau eines universitätsweiten Lerninformationssystems parallel zur Entwicklung innovativer Curricula – zeitliche Entwicklung und Synergieeffekte In: Tavangarian D, Nölting K, editors. Auf zu neuen Ufern – E-Learning heute und morgen, Waxmann Münster New York München Berlin: 217 - 226. 5 SMOLLE J, STABER R, NEGES H, REIBNEGGER G (2005) Computer-based training in dermatooncology - a preliminary report comparing electronic learning programs with face-toface teaching. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 3:883-888. 6 MUSCH J (1999) Die Gestaltung von Feedback in computergestützten Lernumgebungen: Modelle und Befunde. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 13:148-160. Corresponding author Univ.-Prof. Dr. med. univ. Josef Smolle Institute of Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation Auenbruggerplatz 2/V A-8036 Graz, Austria josef.smolle@meduni-graz.at